News

Archive for the ‘Pet of the Month’ Category

Pet of the Month – June 2016 – Polly

by admin on June 1st, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

What is Cushing’s disease and how is steroid produced by the body?

Hyperadrenocorticism or ‘Cushing’s disease’ is caused by excessive production or administration of steroid. It can be classified as pituitary dependent, adrenal dependent, or iatrogenic.

A brief overview of how steroid is produced in the body will help with the understanding of this disease. The pituitary gland is a small gland at the base of the brain that secretes a hormone called ACTH. ACTH causes the adrenal glands to secrete steroid hormone. There are two adrenal glands in animals which are located in the abdomen close to the left and right kidneys. The main steroids produced in response to ACTH secreted by the pituitary gland are glucocorticoids and these have widespread effects on the management of proteins and sugars by the body.

What is the cause of Cushing’s disease?

Approximately 85% of dogs with Cushing’s disease have a very small, typically non-cancerous, growth of the pituitary gland that drives the excessive steroid production (via excessive ACTH production). These dogs have what is called ‘pituitary dependent hyperadrenocorticism’ (abbreviated to ‘PDH’). Approximately 75% of dogs with PDH weigh less than 20kg.

Approximately 15% of dogs have a tumour on one of their adrenal glands that drives the excess steroid production. This is known as ‘adrenal dependent hyperadrenocorticism’ (abbreviated to ‘ADH’). Cancerous and non-cancerous growths occur with equal frequency. Approximately 50% of dogs with ADH weigh greater than 20kg.

What are the signs of Cushing’s disease?

The most common presenting signs in dogs with Cushing’s disease are:

- increased drinking

- increased urination

- increased appetite

- panting

- enlargement of the abdomen

- hair loss

Dogs with Cushing’s disease are usually 6 years of age or older and many different breeds have been reported to be affected including Poodles, various Terrier breeds, Daschunds, Beagles and Labrador Retrievers.

How is a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease made?

The diagnosis of Cushing’s disease can sometimes be difficult, even with blood tests. Blood test results will be interpreted by your vet in light of the history and findings on examination. A blood test taken after the administration of a hormone or drug is necessary to help make the diagnosis. These tests are called the ‘ACTH stimulation test’ and the ‘low dose dexamethasone suppression test’. Normally only one test is necessary; however, occasionally both tests need to be performed. Urine tests are often performed as well.

Once a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease is made, it is useful to know whether the patient has pituitary dependent Cushing’s disease or adrenal dependent Cushing’s disease. The differentiation can be made with further blood testing or with an ultrasound scan of the abdomen. An ultrasound scan of the abdomen is sometimes required to help in achieving a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease.

How are dogs with Cushing’s disease treated?

Dogs with confirmed pituitary dependent Cushing’s disease are managed with an oral drug called trilostane. Trilostane stops the production of steroid and leads to an improvement in clinical signs in most dogs. Trilostane is absorbed better if given with food. Blood testing is necessary after starting treatment to monitor the effect of the drug. Any blood test result will always be interpreted in combination with the clinical signs. The majority of dogs will show a good response to treatment but will require lifelong therapy. Occasionally the small growth on the pituitary gland can grow and cause neurological signs (fits, behaviour change). Scans of the brain are therefore sometimes performed.

Surgical removal of the adrenal gland mass is the treatment of choice for patients with adrenal dependent Cushing’s disease. The outlook depends upon the degree of invasion of the growth into local blood vessels and analysis of the tumour under a microscope. Trilostane can be trialled in those patients for whom surgery is not an option.

‘Iatrogenic’ Cushing’s disease can be caused by the administration of steroid by mouth or topically. It tends to occur in patients on high dose, long term oral steroid (prednisolone) therapy. Treatment involves gradually stopping steroid therapy.

Pet of the Month – May 2016 – O’Riley!

by admin on May 2nd, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

With O’Riley already suffering from Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) his owners were used to him having the occasional flare ups of IBD causing him to not be his normal bouncy self. But when they noticed he was drinking more, urinating more and having more frequent bouts of vomiting as well they brought him in to see if anything else could be contributing to this.

Blood tests showed O’Riley to have higher than normal levels of urea and creatinine, substances which the kidneys excrete, indicating O’Riley’s kidney function was declining. A urine sample was taken to help confirm the diagnosis and also to check if he had excess protein in his urine (‘proteinuria’) as animals with kidney disease who develop this will benefit from additional medications. A clinically silent urinary tract infection was detected, a common complaint for animals with kidney disease, which obscured the protein results. This was addressed with a course of antibiotics before repeating the urine test. O’Riley was found to have proteinuria and started on a medication called an ACE inhibitor. An ultrasound scan of his kidneys was also performed to check for any structural abnormalities and his left kidney was found to be small, a common finding in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD). A renal diet which restricts the amounts of protein and phosphorus, which the kidneys struggle to excrete in kidney disease, was tried but due to O’Riley’s concurrent IBD this treatment had to be abandoned. His phosphate levels were found to be too high and so an additional medication known as a phosphate binder was started. O’Riley also had regular checks of his blood pressure, as hypertension (high blood pressure) is another common result of CKD. When O’Riley’s blood pressure was found to be elevated he was also started on Amlodipine to help reduce this. Blood tests to check on his kidneys a month later showed improvements with lower levels of urea, creatinine and phosphate.

We are delighted to report that apart from an isolated occasion when his kidney disease made him feel unwell and which a brief stay in our hospital on intravenous fluids helped rectify, six months on O’Riley continues to do well.

Pet of the Month April 2016 – Winston!

by admin on April 1st, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags: Tags: cat, feline, vomiting, winston

Young Winston is featured this week as he has fortunately made a swift and complete recovery following treatment for vomiting using an extended course of antacids and a bland diet. Apart from showing off his good looks this article illustrates a common feline problem and the approach taken for pets whose response to treatment is not quite so immediate as his.

You’ve probably witnessed your cat vomiting from time to time without raising too much concern. Vomiting is a protective mechanism that can result from something minor such as overindulgence or access to an irritant, or it can be a sign of a much more serious condition associated with a primary gastrointestinal disorder (e.g. an ingested foreign body) or a systemic disorder (e.g. kidney disease).

What is the difference between your cat vomiting and and your cat regurgitating? Why does it matter?

The oesophagus is a narrow, muscular tube that allows food to pass through on its way to the stomach. In healthy cats, food will move quickly through the oesophagus to the stomach with little to no delay. When you take your cat to your veterinary surgeon because he or she is vomiting, they will ask you questions in attempt to differentiate between vomiting and regurgitation.

Regurgitation is the passive ejection of contents from the oesophagus. The cat will lower its head and food is expelled with little or no effort. The food is usually undigested, may have a tubular shape, and is often covered with a slimy mucus. Cats will also attempt to eat the regurgitated material.

If the muscle of the oesophagus is considered diseased, it will either result in widening of the oesophagus due to loss of muscular tone (called ‘megaoesophagus’), or narrowing of the oesophagus, which acts as an obstruction to material moving down into the stomach (e.g. a stricture, a tumour or a foreign body can all cause narrowing of the oesophagus). A dilated (widened) oesophagus will not effectively, or efficiently, move or push food from the oesophagus into the stomach. This delay can result in regurgitation shortly after eating. The danger of regurgitation is that the contents may also be inhaled into the airways causing pneumonia and a cough. It’s therefore important for your vet to differentiate between vomiting and regurgitation as this will have an impact on deciding which diagnostic tests to perform, and also will help when deciding on the most appropriate treatment options.

Vomiting, on the other hand, is an active process. Cats will often vocalise, be apprehensive and heave/retch to vomit. If food is present in vomit, it is partially digested and can also contain a yellow fluid (bile). Vomiting can be divided down into primary (gastrointestinal) causes, or secondary (non-gastrointestinal) causes.

Primary causes of vomiting are those diseases directly affecting the stomach and upper intestinal tract. Secondary causes are due to diseases lying outside of the gastrointestinal tract and can include neurological disease or accumulation of toxic substances in the blood. Neurological disease and/or toxic substances will stimulate the vomiting centre in the brain and cause the animal to vomit. Additionally, vomiting can be further divided into acute versus chronic causes.

Some common causes for sudden (acute) vomiting in cats include:

- Diet-related causes (diet change, food intolerance)

- Gastric or intestinal foreign bodies (eg. toys, hairballs, or where one part of the intestine moves inside another part of the intestine)

- Gastrointestinal parasites

- Urinary tract causes: acute kidney failure, ruptured bladder

- Acute liver failure

- Pancreatitis

- Ingestion of toxins or chemicals

- Viral infections

- Certain prescribed medications

- Inner ear/neurological disorders

- Decompensation of a more chronic disease

Some common causes for chronic vomiting in cats (vomiting greater than 3 weeks duration) include:

- Gastritis/gastroenteritis (infectious, toxic, dietary indiscretion/intolerance)

- Hyperthyroidism

- Inflammatory bowel disease (gastritis, enteritis, colitis)

- Severe constipation

- Diabetes (ketoacidosis – this is a form of uncontrolled diabetes)

- Chronic liver disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Pancreatitis

- Cancer (gastric/intestinal)

- Inner ear diseases/neurological disorders

- Heart worm disease

What should I do if my cat vomits frequently?

An occasional, isolated bout of vomiting is normal. However, frequent vomiting can be a sign of a more serious condition. Your vet will normally ask you a very detailed clinical history and perform a thorough physical examination. This information can help your vet narrow down potential causes from the very long list of possibilities.

The presence of fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, anaemia or abnormal masses in the abdomen will help your vet make a more specific diagnosis. The mouth should be carefully examined as some foreign objects such as string can entangle themselves around the base of the tongue with the rest of the object extending into the stomach or small intestine. A nodule may be palpated in the neck of cats with hyperthyroidism.

Many times, a full physical examination may be normal and unremarkable. At this stage, your vet may choose to adopt trial treatment/supportive care by implementing a brief starvation period, with or without administration of fluid therapy and various medications (e.g. pain relief, anti-nausea medications, antacids) and assess your cat’s response.

Further investigation of vomiting in cats

Depending on response, your vet may need to perform further investigations to differentiate primary from secondary causes of vomiting. Depending on history, clinical examination, and response to trial therapy, further tests may be needed and may include blood tests, urine analysis and faecal examination to rule out possible toxicities, parasites, and metabolic diseases. Further blood tests may include FIV/FeLV (Feline Immunodeficiency Virus and Feline Leukaemia Virus) to assess viral status. Although FIV/FeLV are not common primary causes of vomiting, they may reflect underlying immunosuppression which may make the cat more susceptible to certain diseases. Your vet may also decide to perform tests to assess the pancreatic health (e.g. pancreatitis).

Depending on the case, your vet may then decide to proceed with ‘second tier’ testing. This usually would involve some diagnostic imaging – x-rays and ultrasound – which can be useful in identifying masses, foreign objects, and other gastrointestinal tract problems such as pancreatitis.

Finally, if indicated, further ‘third tier’ testing may be indicated to obtain a biopsy of intestinal tract tissue if cancer or inflammatory bowel disease is suspected. Biopsies can be collected using either minimally invasive procedures (endoscopy and/or laparoscopy) or more invasive procedures (exploratory laparotomy). Endoscopy (a small camera attached to a long flexible tube) is commonly used to visualise the inside of the oesophagus, stomach and first part of the small intestine and to obtain small biopsies called ‘pinch biopsies’. It may also be possible to provide therapeutic interventions with an endoscope. Laparotomy (open surgery) or laparoscopy (‘key hole surgery’) may be considered for those cases where samples of organs lying outside of the stomach/small intestine and full thickness biopsies of intestines are needed.

This information will help your vet to identify the cause, streamline a treatment plan, and also provide you with a prognosis.

What are some treatment options?

The treatment for vomiting depends upon the underlying cause.

Non-specific treatment may include a 12-24 hour fasting period. Fluids may need to be withheld for a short period of time until vomiting has ceased. Water should never be withheld from an animal with known or suspected kidney disease without replacing fluids intravenously or subcutaneously (under the skin).

Water can be reintroduced in small volumes after a 6-12 hour period. You may wish to start with tuna water (not brine) or chicken broth (with NO added onion/garlic or powders) to encourage fluid intake. Gradual increases in volume may commence over the course of the day if vomiting does not recur.

Provided oral fluids have been well-tolerated, small volumes of a bland, high quality protein source (boiled chicken breast, tuna in spring water, turkey breast, boiled white fish) may then be introduced. It’s advisable to start with a teaspoon size portion every 4-6 hours for 1-2 days. Again, if tolerated, gradual increases in food volume may be attempted with the aim to wean back to the original diet over a 3-5 day period. If a cat is bright and alert and has had no previous health problems, episodes of acute vomiting may be managed at home, although veterinary consultation prior to home treatment is strongly advised. In certain situations (e.g. depression, dehydration, or symptoms lasting longer than 12-24 hours), your cat may require fluid therapy or drugs to help control vomiting. You’ll need to see your vet to determine the proper course of action.

What other symptoms should I watch for?

The causes of vomiting are so varied and can be extremely difficult to accurately diagnose. It’s therefore important to monitor for other signs of ill health that may help direct your vet in his/her quest in identifying the underlying cause.

What to watch for:

- Frequency of vomiting. If your cat vomits once and proceeds to eat regularly and have a normal bowel movement, the vomiting was most likely an isolated incident

- Diarrhoea

- Dehydration (sticky gums, weak, sunken eyes, increased ‘skin tenting’)

- Lethargy

- Blood in vomit

- Weight loss

- Change in appetite and water intake (either increased or decreased)

When is it time to see the vet?

Please see your vet if you notice any of the symptoms mentioned above or if vomiting persists. Depending on your cat’s age, medical history, physical examination findings and particular symptoms, your vet may choose to perform various tests and/or admit your cat for more intensive treatment.

Pet of the Month – March 2016

by admin on March 2nd, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Max developed marked swelling of opposite fore and hind limbs within hours of a muddy walk. Rather uniquely he had emphysema and oedema in his legs. Max was depressed and inappetant and the following day developed skin lesions and a low platelet count was detected on his routine bloods. He was sent to Anderson Moores Veterinary Specialists for fear he had contracted Alabama Rot and he was continued on aggressive fluid therapy, pentoxyphylline, a drug that helps stop vasculitis and general intensive care with frequent monitoring of his platelets and kidney parameters. His urine output was monitored. His feet were maintained in dressings and antibiotics were used for the secondary infections which occurred following the skin lesions and he had opiates for analgesia. Acute Kidney Injury typically develops in 1-10 days so this protocol was continued until he had passed the 10 day mark and then medications were continued until his skin lesions resolved.

Max was home in time for Christmas and we are delighted to report that he has continued to do well.

Pet of the Month – February 2016

by admin on February 4th, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

What a narrow escape Kiki has had! On her night-time travels she slipped when walking through a broken greenhouse and managed to slice her neck open, narrowly missing her jugular vein.

Thankfully she returned home shortly afterwards and on seeing the blood her owner immediately rushed her in to our clinic. We are delighted to report she is doing very well and recovering from extensive corrective surgery – a very near miss indeed!

Pet of the Month – January 2016

by admin on January 4th, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

We are delighted to report that Hadley, who has featured in this column before for eating mussel shells is doing very well after an operation to remove two Mast cell tumours (MCT). Sadly his proclivity for eating unsuitable foodstuffs continued on December 27th when half a Christmas pudding “disappeared’! Induced emesis and intravenous fluids have thankfully settled this unwanted event.

MCT is the most common skin tumour in dogs; it can also affect other areas of the body, including the spleen, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow. MCT represent a cancer of a type of blood cell normally involved in the body’s response to allergens and inflammation. Certain dogs are predisposed to MCT, including brachycephalic (flat-faced) breeds such as Boston Terriers, Boxers, Pugs, and Bulldogs, as well as retriever breeds, though any breed of dog can develop MCT.

When they occur on the skin, MCT vary widely in appearance. They can be a raised lump or bump on or just under the skin, and may be red, ulcerated, or swollen. In addition, many owners will report a waxing and waning size of the tumour, which can occur spontaneously, or can be produced by agitation of the tumour, causing degranulation. Mast cells contain granules filled with substances which can be released into the bloodstream and potentially cause systemic problems, including stomach ulceration and bleeding, swelling and redness at and around the tumour site, and potentially life-threatening complications, such as a dangerous drop in blood pressure and a systemic inflammatory response leading to shock.

When MCT occur on the skin, they can occur anywhere on the body. The biological behaviour of these tumours can vary widely; some may be present for many months without growing much, while others can appear suddenly and grow very quickly. The most common sites of MCT spread (metastasis) are the lymph nodes, spleen and liver.

Diagnosis can be simply achieved via a fine needle aspirate. This requires no anaesthesia and only rarely sedation. Early identification and surgical removal are key to the most favourable outcomes.

Hadley initially found the operation sites to be very itchy after surgery, something not uncommon with MCT. After removing a few of his own sutures Hadley was given additional medication, resutured and had to wear a full body suit! All is now fine.

Pet of the Month – December 2015

by admin on December 2nd, 2015

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

We are delighted to report that Harvey who contracted meningoencephalitis several months ago and has a focal brain lesion is now back home and feeling much better after a recent relapse.

As in humans, the system of membranes which envelops the dog’s central nervous system is called the meninges. If this system becomes inflamed, it is referred to as meningitis. Meningoencephalitis, meanwhile, is the inflammation of the meninges and brain.

This inflammation can result in severe malaise, depression and vomiting as well as neurological symptoms such as impaired movement, altered mental state, and seizures.

Pet of the Month – November 2015

by admin on November 2nd, 2015

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Gemma has had a very lucky escape!

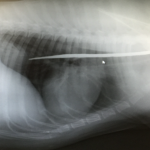

She went lame whilst chasing a ball over the weekend. When this failed to resolve her owner brought her to the surgery for examination. Gemma’s right foreleg was found to be painful and swollen so she was admitted so radiographs could be taken.

We were shocked to discover that a 30cm long metal rod had penetrated her body in the region of her right shoulder and got stuck behind her shoulder blade, missing her chest by millimetres (see image on right). It had obviously been protruding from an unseen object and broken off inside Gemma as she ran by, leaving no visible exterior sign of injury, such as laceration or bleeding, to indicate that she had been impaled.

We used the radiographs to define the rod’s location and it was then surgically removed. We are delighted to report that Gemma, who has been a fantastic patient, is recovering extremely well!

Pet of the Month – October 2015

by admin on October 2nd, 2015

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Poor Jake was recently involved in a road traffic accident. He suffered severe head injuries and developed respiratory difficulties as a consequence.

Jake has been a marvellous patient and has thankfully responded very well to intensive treatment. He is now continuing his recuperation at home.

Pet of the Month – September 2015

by admin on September 7th, 2015

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Just like people, dogs can show allergic symptoms when their immune systems begin to recognise substances -or allergens- as dangerous.

Poor Reny was only playing in the garden for a short period when his muzzle swelled up tremendously and his left eye began to close. It often takes some detective work to find out what substance is causing the allergic reaction and sometimes it is never known. It could be due to an insect bite or sting or a noxious substance to name just a few of many potential causes.

Prompt action brought about a swift resolution although Reny did need to be hospitalised for a short period to monitor him.