News

Special Offer – May – Feline Hypertension Month

by admin on May 1st, 2018

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the month – May – Pepper

by admin on May 1st, 2018

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Pepper is Pet of the Month for May. She is a rescue dog with a chequered past who has recently found a good home. Her new owner is making good progress dealing with her separation anxiety.

Separation anxiety and behavioural problems can occur in dogs when they are left home alone.

Dogs are social creatures that have evolved to live with humans. It isn’t surprising therefore that unwanted behaviour sometimes occurs when a dog or puppy is left ‘home alone’. However, whilst it is often assumed that the problem behaviour is triggered by ‘separation anxiety’, this is not always the case. It is therefore very important that the reason for the unwanted behaviour is clearly identified for each individual.

What sort of problem behaviour is typically seen?

The most commonly reported separation problems in dogs are excessive barking or howling, eliminating indoors and damage to the house or its contents. Dogs may also show physical symptoms such as excessive salivation, or compulsive behaviours such as pacing or excessively licking themselves. Most start to show the problem behaviour as soon as the owner has left, but others may not do so for some time or may start to feel distressed as soon as they realise the owner is about to go out. They may then try to stop them leaving, perhaps by blocking their access to the door or – rarely – by becoming aggressive.

What causes separation anxiety or other problem behaviour when a dog is left alone?

Dogs may show unwanted behaviour when alone for a wide variety of reasons. For example elimination may be an involuntary reflex reaction due to separation anxiety. However, it may also occur because the dog isn’t properly house trained and so eliminates if he is caught short whilst the owner is out. It may be due to a urinary tract infection or another medical problem that makes the dog need to eliminate more often. In geriatric dogs it may be due to declining mental faculties resulting in confusion about when or where to eliminate.

Separation anxiety and other problem behaviour when a dog is home alone may occur for a wide variety of reasons

Destructive behaviour when left alone, such as when the dog scrabbles at a door or window, may be caused by the dog trying to follow the owner due to separation anxiety. Alternatively, the dog may chew out of boredom or may cause damage whilst trying to get to something he wants. It also isn’t uncommon for a dog to spend a happy afternoon raiding the cupboards and fridge when left alone in the kitchen, but to settle perfectly happily if left in a room where there is no access to food. This is more a case of ‘whilst the cat’s away….’ than emotional distress.

Vocalisation may also have multiple causes. Dogs vocalise to communicate and may howl or bark for prolonged periods due to separation anxiety. However, they are also likely to bark if someone approaches the property and they are trying to guard it. It therefore can’t always be assumed any barking or howling is triggered by emotional distress at being alone.

Even where the unwanted behaviour is triggered by emotional distress, this may arise for different reasons in different dogs. Some dogs appear to become overly attached to or dependant on their owner. These dogs seem genuinely distressed at being separated from them. In other cases the distress may be because the dog didn’t learn to feel comfortable being alone as a puppy. He may then become distressed the first time this happens, such as when a family member returns to work or a doggy (or feline) companion dies. Some may bark and scrabble at doors out of frustration because they want to accompany the owner on their adventure into the wide world outside. In a few cases the unwanted behaviour is triggered by something happening when the owner is out that makes the dog scared. This can then lead to the dog becoming fearful whenever they are alone in case it happens again.

How do we know what is causing the separation anxiety or other problem behaviour?

Finding the causes for separation anxiety (or other problem behaviour) requires a careful assessment of what is happening when the dog is both with people and alone. Video recordings of the dog’s behaviour when no-one is there can also be very revealing.

For example if a dog causes damage to doorways as soon as and every time the owner leaves, this is likely to be due to some kind of emotional distress. Observation of the behaviour will show if it is due to anxiety or frustration, and the dog’s history will reveal if it’s due to lack of familiarisation as a puppy or over attachment. If the behaviour doesn’t occur until much later, is directed to household contents and occurs in a young or under exercised dog, it is more likely to be boredom. If the behaviour is intermittent, video recordings may reveal certain triggers for the behaviour, such as when bins are collected in a dog with a phobia of lorries.

How can we prevent separation anxiety and other separation problems in dogs?

Most puppies can be familiarised to being home alone if they are taught to gradually accept this when they are very young. Other problem behaviours can be prevented by teaching your dog to prefer being outside when he wants to eliminate and making sure he has plenty of exercise, stimulation and companionship.

Top tips to help familiarise puppies to being home alone

- Start by leaving when your puppy is tired, well fed and has just been out into the garden

- Place your puppy in a safe area such as his crate or a puppy proofed area of the house

- Give your puppy something engaging e.g. a new toy, or a food item such as a Kong with a small amount of food inside

- Leave calmly but don’t sneak away – it is important that your puppy knows you have gone

- Initially leave for just five minutes. Make sure you are somewhere your puppy cannot hear, see or smell you

- Come back after the allotted time regardless of what is happening e.g. barking or whining

- If your puppy is quiet he can be greeted immediately

- If he is making noise ask him to ‘sit’, then give attention when he obeys. If he doesn’t yet know this command just wait for him to be quiet then greet him. Don’t ignore him for long periods as this is punishing

- Repeat 3-4 times a day. He should quickly stop being concerned by you leaving and settle to his toy or food item

- You can then start to increase how long he is left for. Start by increasing this by five minutes at a time, up to 30 minutes, then by 10 minutes at a time up to an hour. Each increment should be repeated 3 or 4 times. As the duration he is left for goes up the frequency can reduce

- Even puppies that live with another dog must learn to be alone

How can we stop this behaviour?

If prevention hasn’t worked then the method of correction will depend on the cause. For example, if indoor elimination is due to a lack of house training this can be rectified by teaching the dog to prefer to be outside to eliminate using similar methods to those used with puppies. If the dog is being destructive due to boredom this may be helped with toys, improvements in overall exercise and stimulation or reducing the period of time the dog is left alone. However more complex problems may require a tailored treatment package developed specifically for your dog’s needs by a specialist in this area. If your pet is showing problem behaviour when left alone then discuss this with your vet. They will be able to rule out any underlying medical problems and, if necessary, refer you to a suitably qualified behaviour expert.

FELINE HYPERTENSION

by admin on May 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

To encourage awareness of Feline Hypertension this month we are offering the owners of all cats over 8 years of age with no previous history of hypertension a FREE Screening test with one of our nurses.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, usually occurs in cats secondary to other diseases. The most common diseases to cause high blood pressure in cats are chronic renal failure (kidney disease), hyperthyroidism and anemia. Cushing’s disease and certain forms of cancer can also cause high blood pressure.

Hypertension is a serious problem in the cat, as it can cause blindness and strokes, just as in people. The first symptom seen is usually sudden blindness from retinal detachment – the high blood pressure literally blows out the back of the eye. If retinal detachment is caught early, with prompt and aggressive drug treatment the retina will sometimes reattach itself at least partially, and some vision will be restored. Many cats, however, will be permanently blind as a result. Owners will sometimes notice the cat’s pupils are fixed and fully dilated, or only respond very slowly and sluggishly to light. This is an emergency situation which should be treated as soon as possible.

The other common symptom of untreated high blood pressure is bleeding into the brain. Cats may suddenly show signs of disorientation, circling around and around in one spot, or otherwise acting strange. Some cats will wander the house crying as if distressed.

Ideally, high blood pressure should be diagnosed and treated before the cat becomes blind or suffers brain damage. If your cat has been diagnosed with chronic renal failure, hyperthyroidism or anemia, a blood pressure check will probably be recommended as well.

Some cats with high blood pressure will have heart murmurs or abnormal heart rhythms. If your veterinarian picks up a heart murmur or arrhythmia in a cat, especially an older cat prone to kidney or thyroid disease, a blood pressure check will be recommended. We may also pick up on high blood pressure when we draw a blood sample – if the blood gushes into the syringe without our having to pull back on the

plunger, the cat’s blood pressure is probably very high.

About 65% of cats with chronic renal failure have some degree of hypertension. This is a serious problem because hypertension in turn worsens the kidney disease. It becomes a vicious cycle in which the high blood pressure worsens the kidney disease, which increases the blood pressure even more, which then worsens the kidney disease, etc. Any cat diagnosed with chronic renal disease should have a blood pressure check on a regular basis.

In cats with hyperthyroidism the hypertension is usually temporary. Once the thyroid disease is controlled with medication or radiation treatment, the blood pressure goes back down. Treatment for high blood pressure in this disease is usually only needed for a few weeks to months. Treatment is still important, however, to prevent blindness and brain damage.

Although blood pressure measuring is important to monitor, it can also be difficult to do accurately in cats. Most cats are stressed and nervous at the veterinary clinic, and some are hostile. Blood pressure readings will probably be higher than they would be if measured when the cat was at home in its own environment. If a cat is aggressive or terrified, readings may not be possible at all. We will advise you as to whether an accurate blood pressure reading is possible in your cat.

We try to make the experience as stress free as possible, in a quiet room. The measurement itself is painless, just as it is in humans, but the cat may be frightened by the procedure. The cat needs to be held still, and a Doppler monitor is used to get the measurement. The monitor makes a noise which may frighten to some cats. The feeling of the cuff on the leg also makes some cats nervous, as does being held.

The goal of treatment is to decrease the blood pressure gradually to avoid a sudden decrease in blood flow to the kidneys, which will make kidney disease worse. In cats with chronic renal failure and high blood pressure, the pressure should be rechecked every 3-7 days, depending on how good the first reading was. Once two good readings on two successive visits are obtained, the cat is considered stable on the medication. The blood pressure is then rechecked along with kidney blood testing about every three months. Drug treatment will be necessary for the rest of the cat’s life.

There are two medications commonly used to treat hypertension. Amlodipine is usually tried first. If the response is not adequate, we may switch to benazapril. Occasionally, a cat will need both amlodipine and benazapril to control the high blood pressure.

For cats with chronic renal failure but a normal first blood pressure check, rechecks are recommended every 6-12 months. Hypertension may show up later in the course of the disease, as kidney function gradually worsens with time. In cats recently diagnosed with hyperthyroidism, the blood pressure may be high. If affirmative we will prescribe a two to three week course of blood pressure medication for the cat while the thyroid level is coming down in response to treatment. Once the thyroid level is back in the normal range, the medication can usually be stopped.

Cats that have already suffered blindness or visual impairment from hypertension usually get around well in their own home with some modifications to the environment. Your cat may not be able to find its way to the basement litter tray any more but blind cats rarely stop using the tray as long as it is accessible to them. Be sure the food and water bowls are also accessible without climbing or jumping. Dabbing some perfume or cologne on table legs and doorways once a week at first with help your pet to smell where it’s going and makes navigation easier.

Be sure to call us if you have trouble administering your cat’s medication or you notice any change. We are always glad to help!

See website: http://www.amodeus.vet for further information

HOME MONITORING OF HEART FAILURE

by admin on April 3rd, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

This article provides key aspects of monitoring your pet with heart failure at home and explains the parameters to record. These need to be monitored frequently (daily) in the few weeks after initial diagnosis and commencement of medications, or at any time when things are unstable, such as a relapse or progression in symptoms. The frequency of recording can be less (weekly) when everything is stable and your pet is happy. You can record all of these using a diary or computer database. Remember to always bring your record back with you to every visit.

Sleeping Respiratory Rate (SRR)

This should be recorded when your pet has had a period of rest and is asleep. This might be by your feet or in bed. It is best to record this when your pet falls asleep when you are in the room, as opposed to going into the room where your pet is already asleep – as they usually wake up when you enter.

Breathing is often best seen when your pet is lying on the side and the chest and flank can be seen to rise and fall. A breath in and then out is recorded as one breath. The rate is given as the number of breaths in 1 minute.

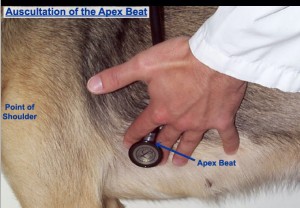

Heart rate (HR) at rest:

This is more difficult to record, but it is possible to do and it provides very useful information. The heart rate when ‘in the vets’ is always somewhat elevated because of excitement or nervousness, so does not represent the real heart rate at home.

The heartbeat can be felt by placing your hand on the chest over the heart, just inside the ‘armpits’ on the left side, but can be either side of the chest. You could purchase a cheap stethoscope and learn to listen to the heart rate. Feeling the pulse in the leg does not always represent the heart rate, as some abnormal or weak heartbeats might not produce a palpable pulse, so we prefer that you do not use this method.

You could purchase a heart rate monitor, and whilst these are a little more expensive, over the course of your pet’s life, often represent good value for money. The rate is given as the number of heartbeats in 1 minute.

Weight

One of the effects of heart failure is the accumulation of excess fluid in the lungs (oedema), chest cavity (pleural fluid) or abdomen (ascites). One litre of fluid is equivalent to 1 kg in weight. Thus monitoring your pet’s body weight is a useful means to track the loss or gain in fluid accumulation.

We recommend weighing your pet weekly. It is often best to use the scales at your own vets for consistency and accuracy.

Appetite

Your pet’s appetite may reflect his/her well-being. It is a simple scoring system, comparing appetite to when your pet was well prior to this illness and is as follows:

Appetite Scores:

1 Ate hardly anything

2 Ate much less than normal

3 Ate a little less than normal

4 Normal

5 Ate very well

Exercise

Once any congestion has resolved with treatment, a return to some exercise is good for the well-being of your pet and for the circulation. The ability to exercise also reflects the ability of the heart to function and circulate blood, so it can be a useful indication of how well your pet is doing. Again this is a simple scoring system, comparing the ability to exercise to when your pet was well prior to this illness and is as follows:

Exercise Scores:

1 Can hardly exercise at all

2 Is exercising much less than normal

3 Is exercising a little less than normal

4 Normal

5 Exercises very well

Cough

Coughing is a common symptom in dogs (it is rare in cats). This can occur for a few reasons. One is that an enlarged heart presses on the windpipe, compressing it and this triggers a cough; it probably feels like something is stuck in the throat. Another is the accumulation of fluid in the lungs (oedema), this needs to be moderately severe to trig, of course,h. Then of course a dog (or cat) can be coughing secondary to various lung conditions such as bronchitis (or asthma in cats). Monitoring the frequency and severity of a cough can therefore be useful.

Cough Scores:

1 Very often, daily

2 Often, daily

3 Often, weekly

4 Occasionally, weekly

5 None

The Happiness Factor

This is a surprisingly useful overall score of how well your pet is. It is a simple scoring system, comparing how happy your pet is compared to when your pet was well, prior to this illness and is as follows:

Happiness Scores:

1 Very unhappy

2 Much less happy than normal

3 A little less happy than normal

4 Happy, back to normal

5 Really happy

Pet of the month – April – Hank

by admin on April 3rd, 2018

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

In his owners words:

“Hank, my 7 year old black Labrador had been competing in a working test on Sunday and wasn’t his usual self. He seemed reluctant to jump and just wasn’t as obedient as he normally is. I have no idea if he was already feeling a little off colour that day, and guess I will never know. Within 45 minutes of eating his dinner that evening he started to try and vomit, but nothing was coming up. He was stretching, lying in the praying position and just generally not looking very happy. I was immediately suspicious that this could be a torsion and so I rang Lisa and Kate who agreed to see him. By the time I got to the surgery at 6.30 pm he was clearly becoming distressed, so we x-rayed his abdomen and it was showing that indeed he had a twisted stomach. By then was pale and shocked and his abdomen was getting larger by the minute. Hank was put on fluids and prepped for surgery. His surgery lasted over 3 hours, but was thankfully successful.

Only 48 hours after surgery, Hank was allowed home, and has made an amazing recovery. He is now training once again and exercising normally. I guess after all the years working at Fitzalan House I have learnt a thing or two as I managed to spot the signs of what was happening but without the prompt veterinary care he received I could have easily lost him. I am so very grateful for Lisa and Kate’s attention to him that night, they undoubtedly saved his life, and I cant thank them enough.”

What is gastric-dilatation and volvulus (GDV)? Is my dog at risk? Gastric dilatation and volvulus, or GDV as it is commonly abbreviated, is a relatively common clinical syndrome seen in large / giant breeds of dog. Dilatation refers to bloating of the stomach with gas, and volvulus refers to twisting of the stomach about its axis. The cause of this syndrome is not completely understood. In fact it is quite controversial which occurs first; the bloat or the volvulus (twisting). Indeed both components do not have to occur together and some patients will develop relatively simple bloat alone. GDV is a potentially life threatening condition and emergency veterinary attention should be sought immediately if it is suspected.

Why is GDV potentially life-threatening to dogs?

There are a number of serious and potentially fatal consequences that occur as a result of GDV. Initially the severe distension of the stomach stretches the blood vessels over its surface reducing the blood supply to the stomach walls. This is made worse by the twisting of the stomach which also twists the blood vessels, effectively shutting off blood supply to the stomach. A lack of blood flow means there is a lack of oxygen and nutrients delivered to the stomach and waste products are not removed. As with any organ this will result in parts of it dying. This process happens very quickly and in severe cases could result in part of the stomach wall rupturing and releasing its contents into the abdomen.

The large distended stomach occupies much more space inside the abdominal cavity and compresses surrounding structures. Severe distension puts pressure on the diaphragm and interferes with the patient’s ability to breath. It also applies pressure to a large blood vessel in the abdomen (the vena cava) that normally returns blood from the back half of the body to the heart. Pressure on this vessel obstructs flow therefore reducing the amount of blood returned. If blood can’t be returned to the heart, then it in turn can’t pump it out to the rest of the body. If there is insufficient blood being pumped, the blood pressure falls dramatically making the patient weak and potentially leading to collapse.

To add insult to injury, other organs in the body such as the lungs, kidneys, liver and intestines do not receive a blood supply and begin to fail. The lack of a functional circulation also means that toxic products build up in these organs that further compromise the patient. These changes can happen in a matter of hours, emphasizing the importance of early veterinary attention.

What are the symptoms of GDV in dogs?

The symptoms generally include obvious distension or enlargement of the abdomen with unproductive vomiting or retching. The patient may drool excessively and appear restless or agitated. As the condition progresses the patient may become increasingly weak or even develop shock and collapse.

What is the treatment for GDV?

The age and breed of the patient coupled with the clinical signs of a severely bloated abdomen will make your vet highly suspicious of this condition. They will immediately place one or more an intra-venous catheters to allow administration of fluids to support the circulation and dilute toxins in the blood. They may also analyse the patient’s blood to assess the severity of organ damage.

The next stage involves attempts to decompress the stomach. This is usually accomplished by passage of a specially designed tube through the mouth down into the stomach. There is a gag that can be used to assist in this process but many patients will require sedation or anaesthesia to complete the task. It can be very challenging or sometimes impossible to perform stomach tubing. This is particularly the case when the stomach is twisted 360 degrees or more. In this instance a cannula (tube) may have to be inserted through the body wall and into the stomach to allow deflation. Deflation is clearly an imperative step because it will relieve pressure on the diaphragm and help restore blood flow back to the heart through the vena cava.

Radiographs of the abdomen are often required to help distinguish between simple dilatation and dilatation with volvulus. In the latter case surgery will be required as soon as the patient is stabilised. The aim of the surgery is to de-rotate the stomach and assess it for areas of devitalisation. If there are areas of the stomach that have undergone necrosis (died), these need to be removed surgically.

It is vital that the stomach is attached to the inside of the body wall. This is called a gastropexy and it will prevent volvulus in the future. This is essential as up to three quarters of the patients that do not have this performed will have another episode in the future. This also applies to those patients suffering with bloat alone as they have the same risk.

What are the risk factors for GDV in dogs?

There are several factors that have been clearly demonstrated to increase an individual’s risk of developing this condition. These include:

- Being a purebred large / giant breed

- Having a deep and narrow chest conformation

- Having a history of previous bloat

- Having a history of bloat or GDV in a first degree relative (parent or sibling)

- Increasing age

- Having an aggressive or fearful temperament

- Eating fewer meals per day

- Eating rapidly

- Being fed a food with small particle size

- Exercising or stress after a meal

What breeds are predisposed to this condition?

The breeds most commonly affected are large purebred dogs that have a narrow deep chest confirmation. Those at most risk include:

- Great Danes

- Gordon setters

- Irish setters

- Weimaraners

- St. Bernard’s

- Standard poodles

- Bassett hounds

Although these are the breeds we typically see GDV in, it is worthy to remember that it can happen in any patient.

What is the prognosis?

With improved understanding of the secondary consequences of GDV and excellent anaesthesia, surgical and post-operative care now available for veterinary patients a good prognosis can be achieved for this condition. Survival rates of 73-90% would be typical. There will always be a range quoted for survival because individual patient’s circumstances in terms of severity, age, general health and treatment received will have an impact on the outcome. One important factor that has been shown to decrease the survival is the presence of clinical signs for greater than six hours. This emphasizes the importance of prompt veterinary attention in all cases.

If you are in any doubt that your dog is suffering from bloat or GDV, please call your vet immediately.

What is a Heart Murmur?

by admin on March 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

Hearing your vet announce that “your pet has a heart murmur” can be very daunting. However, the significance of a murmur very much depends upon the situation. Just as a fever can be something or nothing, a murmur may be similar – it may be insignificant, but it could also be a symptom of a disease that requires treatment. So, first of all, what is a heart murmur?

Simply put, a murmur is a sound produced by a squirt of blood inside the heart when it pumps. There are many causes of a murmur.

There are three sections in this information sheet:

- Murmurs explained

- FAQs about murmurs

- List of the common causes of murmurs in dogs and cats

1. Murmurs explained

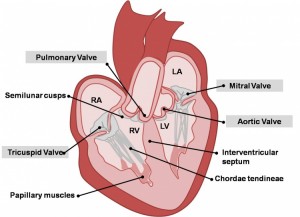

Murmurs due to regurgitation

Each of the four valves in the heart act as non-return valves, permitting blood flow in one direction (forwards). If a valve becomes faulty and no longer prevents backflow, then there is a resultant backward squirt of blood through the gaps in the valve with each heartbeat. This backward squirt of flow through an incompetent valve results in an abnormal heart sound called a heart murmur. A murmur thus sounds like a ‘squirting’ or ‘gushing’ sound during each heartbeat. The most common cause of an incompetent valve in older dogs is Mitral Valve Disease, or Endocardiosis, as it is also known.

Murmurs due to narrowed valves

If a heart valve is abnormally narrowed, usually due to a congenital defect (eg. Aortic Stenosis or Pulmonic Stenosis) then blood flow pumped out through the narrowed valve is pinched, resulting in an abnormal squirt of flow, ie. a murmur. This can be likened to putting a thumb over the end of a hose pipe to make the water squirt, rather than pour.

Murmurs due to ‘holes in the heart’

A murmur can also occur through a hole in the heart – the murmur is caused by the squirt of blood going through the hole. A hole between the left ventricle and right ventricle results in a squirt of blood being pushed through the hole when the heart ventricles pump (this is called a Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)). A hole between the aorta and pulmonary artery (the two major arteries leaving the heart) results in blood squirting through the hole (this is called a Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)).

Puppy murmurs

In puppies less than 6 months of age, in addition to murmurs produced by congenital defects, puppies can have innocent or benign murmurs – often called a puppy murmur. These occur due the fast flow of blood in such a small heart. As the puppy and its heart grow and mature, then the murmur gradually disappears. It is virtually impossible for a vet to discern the difference between a puppy murmur and a congenital defect. If a murmur persists beyond 6 months of age, it is more likely to be a congenital defect.

Murmurs associated with illness

A murmur can also be produced when a dog is anaemic and the blood thin. In this situation, thinner blood (less viscous) results in a faster speed of flow and thus a murmur. A similar situation can occur when a dog is ill for other reasons, such as during a fever.

2. FAQs about heart murmurs in cats and dogs

What is the significance of a murmur?

This depends upon what the cause of the murmur is from the list above, whether the defect causing the murmur is classified as: mild, moderate or severe, and whether it is resulting in heart enlargement or not.

Is the loudness of a murmur significant?

Not always. It depends upon what the cause of the murmur is from the list above. Some murmurs are innocent and of no clinical significance, whereas others are associated with defects. Many defects can be mild and have no effect on the heart and animals can live a full and normal life with them, whereas other defects affect the heart and may need some form of treatment.

Do all these murmurs sound different for each defect?

No, in fact they virtually all sound the same. The squirt (murmur) is heard when the heart beats, so the murmur is brief. The only defect that produces a slightly different sound is a PDA – the murmur is continuous rather than intermittent or brief.

Listening with a stethoscope is not easy and many vets find this difficult. As humans, we all have differing skills and abilities, so there is a lot of variation. It is likely that a veterinary cardiologist will hear murmurs better, because they have had a lot more practice and experience, as well as additional training.

What is the best way to diagnose a murmur?

Nearly always, an ultrasound scan (echocardiography) is the best way to diagnose a murmur. But sometimes additional tests are also required, such as chest x-rays, ECG or blood tests. Echocardiography is a difficult and skilled examination that is best performed by an experienced clinician.

3. List of the common causes of murmurs in dogs and cats

Defects can be congenital, meaning an animal has been born with the defect. Or there can be changes in the heart that develop in adult life, for example due to ageing degeneration of a valve.

Murmur due to Mitral Valve Regurgitation:

- Mitral Valve Disease (MVD) is the most common cause of a murmur in adult dogs in older age

- Mitral Valve Dysplasia is a congenital defect of the valve

- Mitral Valve Regurgitation can occur secondary to heart enlargement of other causes in dogs

- Mitral Valve Regurgitation can be secondary to cardiomyopathy in cats

Murmur due to Aortic Valve Stenosis:

- Subaortic Stenosis and Valvular Aortic Stenosis is a congenital defect of the valve

- Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in cats, often causes ‘Subaortic- like Stenosis’

Murmur due to Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation:

- Tricuspid Valve Disease occurs in adult dogs in older age, most will also have MVD

- Tricuspid Valve Dysplasia is a congenital defect of the valve

- Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation can occur secondary to Pulmonary Hypertension

- Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation can be secondary to heart enlargement of other causes

- Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation, when mild, can be seen in some normal dogs

Murmur due to Pulmonic Valve Stenosis:

- Valvular Pulmonic Stenosis is a congenital defect of the valve

Murmurs associated with holes in the heart:

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus is a congenital defect resulting in abnormal flow between the aorta and pulmonary artery

- Ventricular Septal Defect is a congenital defect in which there is a hole between the two ventricles

Innocent murmurs

These are murmurs due to abnormal flow within the heart and not due to a defect in the heart, ie. there is no congenital defect or degenerative disease. There are a number of causes, these are just some examples:

- Puppy murmurs are innocent murmurs that usually disappear by 4-6 months of age

- Anaemic murmurs are due to the blood being thin

- Fever murmurs are due to turbulence in blood flow

- Flow murmurs are seen in some athletically fit dogs, ie. a murmur with no defect present

Special Offer – March – Wellness Screen Offer

by admin on March 1st, 2018

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the month – March – Poppy

by admin on March 1st, 2018

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Meet our wonderful slimmer, Poppy. She started Sienna’s weight clinic at a whopping 17kg and now weighs 12.7kg. Her overall weight loss is absolutely enormous! Poppy and her owners have done so well to achieve her target weight!

Meet our wonderful slimmer, Poppy. She started Sienna’s weight clinic at a whopping 17kg and now weighs 12.7kg. Her overall weight loss is absolutely enormous! Poppy and her owners have done so well to achieve her target weight!

Her quality of life has improved dramatically. She attends hydrotherapy once a week for her hip problems and now swims with jets on because she’s too good!

Congratulations Poppy!!

Canine obesity is in fact the most common nutritional disorder seen in dogs. As with humans, it’s caused by an imbalance of taking in more energy than giving out. This can give rise to a persistent and potentially life threatening energy surplus.

How to know if your dog is overweight

Signs of canine obesity include owners struggling to see or feel their dog’s ribs, spine or waistline; abdominal sagging; a bigger, rounder face; a reluctance to go for walks or lagging behind; excessive panting; and the dog appearing tired and lazy. Grossly overweight dogs may even need assistance getting up and down, in and out of vehicles, and often refuse to move or play games.

Problems associated with obesity

Vets see these problems all too often, with obese pets posing greater risks from anaesthetic and surgical complications, heat or exercise intolerance, complications from cardio-respiratory disorders, hormone problems, skin disease, cancer, urogenital disorders, even early death. Canine obesity may even contribute to tracheal collapse and laryngeal paralysis too.

Common canine problems suffered as a result of obesity include diabetes (where the pancreas fails to secrete enough insulin in order to regulate blood glucose levels); heart disease (caused by high cholesterol levels); as well as arthritis directly affecting mobility, making it even harder for your pet to lose weight.

Until fairly recently, fatty tissue was thought to be just a relatively lifeless energy store and insulator; but we now know it secretes hormones affecting appetite, inflammation, insulin sensitivity and bodily function, as well as influencing water balance and blood pressure leading to kidney disease and high blood pressure.

Ways to prevent obesity

If your dog is overweight then carefully start changing his feeding habits; increasing exercise (e.g. more or longer walks, or take up a canine activity such as agility or flyball); looking at the type of food and his intake; creating a feeding plan.

One of the very best ways is to make regular visits to your vet nurse for weight loss advice and to have free weight checks and record your success.

Come and join our weight clinics today! There is a small £5 joining fee after which you and your pet receive a weight management booklet with tips on keeping your pet at a healthy weight, body condition score chart, measuring cup, calorie chart of common treats, food diary and leaflets on foods available to help your pet lose weight.

This is followed by regular free of charge check-up appointments to ensure your pet reaches his/her optimal weight.

Phone today to book an appointment with our weight management nurse Sienna!

Lens Luxation

by admin on February 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

What is the lens?

The lens is a large transparent structure within the eye lying just behind the black part of the eye (the pupil). The lens helps to focus light onto the back of the eye. It is normally held in place by tiny threads all around its edge.

What happens in lens luxation?

In patients suffering from lens luxation (dislocation), the lens shifts out of position and moves either into the front or into the back of the eye. If the lens becomes trapped in the front of the eye, it can cause water-logging of the window of the eye (seen as blueing of the front of the eye) and an increase in pressure within the eye (glaucoma). If it falls into the back of the eye, the lens can damage the sensitive tissue at the back of the eye (the retina) and cause it to loosen (retinal detachment). This can also lead to glaucoma. In both cases, the eye is usually painful, and blindness develops unless early appropriate treatment is given.

What causes lens luxation?

Many cases of lens luxation are hereditary and caused by a weakness in the threads holding the lens in place. This condition is called primary lens luxation and is common in the Jack Russell and other terriers. It is also occasionally seen in other breeds and crossbreeds.

Some cases of lens luxation are due to other eye diseases such as cataracts, inflammation within the eye or chronically increased intraocular pressure (glaucoma). These diseases cause damage to the threads that hold the lens in place and as a result it eventually comes loose.

What are the signs of lens luxation?

In most cases of primary lens luxation, the disease develops very rapidly. In the very early stages the eye may just look slightly red and sore. These signs may be misinterpreted as simple conjunctivitis but are in fact the beginning of a potentially blinding disease. Later the patient is often depressed and reluctant to exercise.

The eye usually appears red and painful, often with a bluish tinge over the cornea. As the pressure in the eye goes up, the optic nerve at the back of the eye (which takes messages from the back of the eye to the brain) becomes damaged and blindness results.

How is lens luxation diagnosed?

Once the lens completely dislocates it is relatively straightforward to see that it is out of position in most patients. In addition, examination by an ophthalmic specialist using specialised equipment may enable a diagnosis of lens luxation to be made well before the lens actually dislocates out of position.

Is treatment possible?

Lens luxation is a serious, blinding painful condition. Although medical management of primary lens luxation is an option, in most cases surgical removal of the lens is likely to give the best chance of preserving vision. Lens removal may also be indicated if the lens has luxated as the result of other eye conditions, but each of these cases must be assessed on their individual merits.

The surgical removal of a luxated lens is an operation that should only be carried out by an eye specialist as it requires special training and skills, the use of an operating microscope and microsurgical instrumentation. The surgery also requires the use of a special muscle-relaxant anaesthetic, as the eye must be held absolutely still in the right position during the operation. During the procedure the patient’s breathing is taken over by the anaesthetist. Again, specially trained staff are required to monitor this anaesthetic.

In surgery for lens luxation, the cornea, which forms the clear window at the front of the eye, is incised and the luxated lens is gently removed. The inside of the eye is coated with special gel during the procedure to help to protect its delicate structures. Some of the natural jelly at the back of the eye (the vitreous) also needs to be removed during the operation, and this is performed using highly specialised mechanised equipment. The wound is stitched with suture material finer than a hair. The stitches dissolve over a period of weeks after the surgery.

Following surgery, intensive medical treatment is required, and several re-examinations are necessary to give the best chance of a successful outcome.

Will my pet cope without a lens?

Most pets cope well without a lens but will need a while to adapt to the new vision. Most dogs without lenses are able to avoid bumping into objects, and many can still chase a ball.

Success chances and possible complications

The chance of a successful outcome depends in part upon the duration of the problem prior to presentation and also whether the lens is completely dislocated at the time of surgery. In early cases, the outcome of surgery can be very satisfactory, but in longstanding cases, the success chances are significantly reduced.

Unfortunately, blinding complications are seen in a significant percentage of cases – up to 30% or 40% depending upon the condition of the eye and duration of the problem by the time of surgery. These complications include persistence of glaucoma, bleeding into the eye and retinal detachment.

Even after successful surgery which has saved vision, it may be necessary to continue with long-term medication, especially to keep the pressure in the eye under control. This may in turn require patients to be returned for check-ups from time to time.

Does the condition affect both eyes?

Yes, unfortunately, primary lens luxation affects both eyes, although not necessarily at the same time. However, there will often be early signs of partial dislocation of the lens in the second eye at the time that the first eye is noticed to have a problem. Without treatment, the second lens will then usually dislocate within a few months of the first, and the natural progression of patients with this condition without surgery is to become blind in both eyes. Glaucoma then usually develops, and this not infrequently means that one or both eyes may need to be removed in order to relieve pain.

Is preventative treatment available for the second eye?

Yes, especially in cases of primary lens luxation. If the earliest signs of lens instability (subluxation) are detected at the time that the first eye is affected then the lens may be surgically removed. Early removal of unstable lenses carries the best chance of long-term success. In early cases, it may be possible to perform the surgery through a smaller incision using specialised equipment, and this, in turn, helps to give a better prognosis.

What happens if vision is irreversibly lost in an eye with a luxated lens?

Eyes that have lost vision irreversibly due to lens luxation are not suitable for lens removal. Because many eyes with lens luxation are painful, it may be necessary to consider removal of the eye under these circumstances.

What happens if an eye needs to be removed?

Eye removal is generally only recommended if the eye is painful and blind and the pain cannot be readily controlled with medication. The thought of an eye being removed may be alarming at first, but it is important to realise that this will generally make the patient feel much more comfortable and much happier very quickly. The hair is clipped at the site of the operation but soon grows back, and this then leaves hairy skin where the eye used to be. There is no hole left behind, and the result is cosmetically perfectly acceptable. And of course our patients don’t look at themselves in the mirror and worry about their appearance, they just feel more comfortable and get on with life!