News

Archive for the ‘News’ Category

Ear Disease

by admin on September 7th, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

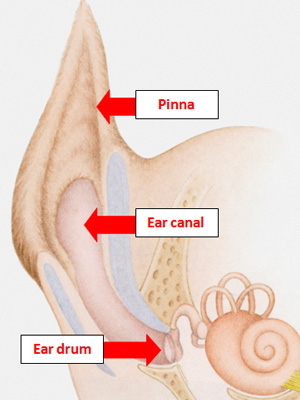

Ear disease is a very common problem in companion animals, and most vets working in practice will diagnose it on a daily basis. The ear canal is an L-shaped tube lined by skin and it culminates at the deepest part with the ear drum. The ear flap (pinna) and canal help to funnel sound waves down to the ear drum for normal hearing to occur. Ear disease can affect one or both of the ears and can occur in conjunction with skin disease at other body sites too. For this reason, vets frequently examine the whole body even though the ears seem to be the main problem.

There are numerous causes of ear disease, with some being very common and others extremely rare. Contrary to popular belief, features such as excessively hairy ear canals and long floppy ears in certain dog breeds do not result in ear disease on their own. However, they can contribute to the problem, and can also make treatment more difficult.

Parasites

One of the most common causes of inflammation in a dog’s ear is a microscopic parasitic mite called Otodectes cynotis or the ‘ear mite’. This mite is usually acquired from other animals and lives down in the ear canal. The inflammation it causes results in pain and itching and a build-up of waxy debris. More rarely, other parasites such as Demodex mites can also cause ear inflammation.

Allergies

The allergic skin diseases of dogs frequently cause inflammation of the ear canals. This group of diseases cause recurrent or relapsing ear disease beginning in early life, often between the ages of 6 months and 3 years. In some cases, dogs with allergies to environmental or food substances have ear disease as their only symptom. Allergic disease in dogs is very common.

Foreign bodies

The active and adventurous lifestyle of dogs means that there is often scope for foreign objects to fall down the ear canals and trigger ear disease. Plant material like grass seeds are common causes, but just about anything from the environment could have a similar effect. Foreign bodies are a very common cause for ear disease in dogs.

Hormonal diseases

Middle aged to older dogs are more likely to suffer from this group of diseases. In rare cases, some of these hormonal diseases can lower the body’s immune system and result in ear disease.

Autoimmune diseases (where the immune system attacks the cells of the body)

These diseases are all very rare, and usually cause skin disease at other body locations too. However, they can result in inflammation in the ear canals and result in ear disease.

Scaling skin diseases

Some dogs with greasy and scaly skin diseases can also develop ear disease. These dogs are also particularly prone to ear infections. These diseases are a relatively rare cause of ear disease in dogs.

How does ear disease in dogs usually present?

Ear disease usually presents with either scratching at the affected ear or head shaking, but some pets present with both. Other pets will rub their heads due to the irritation or hold their heads to one side. A build-up of ear wax is commonly seen, and in some cases where infections are also present, discharge builds up. Some pets present with discharge that looks like pus. When this occurs, most owners will also notice an unpleasant smell. When the inflammation is severe, it can be very painful and pets will often cry when the ear is touched.

How is ear disease in dogs diagnosed?

Ear disease should be diagnosed by a vet, as it is necessary to examine the ear using an instrument called an otoscope. This allows the ear canal to be examined in detail, and often allows the cause to be identified (such as parasites or a foreign body).

Swabs are sometimes taken from the depths of the canals to see if the ear is infected by bacteria or yeast organisms. These microbes, which are often in the ear canal normally, frequently cause a problem once ear disease has been triggered by something else. Once an infection is set up, treatment for this is also needed.

How is ear disease treated?

Luckily, treatment of ear disease is usually relatively straight forward. Identification of the initial trigger is important, as failure to do so will often result in relapses. If mites are found, spot-on products are frequently prescribed to treat them. If foreign objects are seen by your vet on examination of the ear canal, removal is needed. This often needs to be done under sedation or anaesthetic to avoid the risks of damaging the deeper structures like the ear drum. If allergies are diagnosed, further investigations for these diseases will be recommended by your vet.

If infections are identified, ear drops are usually prescribed, and they are used until the infection has been brought under control. Ear cleaning solutions are also sometimes used to help break up the waxy debris and return the ear canal to normal.

In summary, ear diseas is a very common problem, and many pets experience it at some point in their lives. Although there are a number of causes, careful identification and appropriate treatment can ensure a very successful outcome.

Liver disease in dogs

by admin on July 31st, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

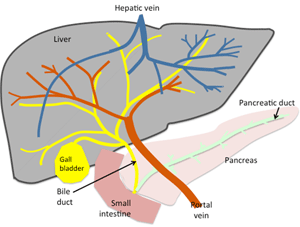

The liver is one of the largest organs in the body; about 3.5% of the body mass. It is situated just behind the diaphragm that separates the chest from the abdomen. The liver is very important and has many functions. Because of its central metabolic role it is affected by many disease processes that occur outside the liver such as endocrine (glandular) conditions. Liver disease in dogs can occur, but fortunately it can often be effectively managed.

What does the liver do?

The liver has many functions that are listed below:

- Carbohydrate metabolism – glucose, glycogen, hormones

- Lipid metabolism and storage

- Protein metabolism (including coagulation proteins)

- Vitamin metabolism and storage

- Immunologic function

- Endocrine hormone metabolism

- Mineral storage – copper, iron, zinc

- Haematologic function

- Digestive function – bile and bile acids

- Detoxification and excretion

The liver has two major parts – the liver cells themselves (hepatocytes) that undertake the metabolic functions of the liver, and the biliary system.

What types of liver disease do dogs get?

Broadly there are three areas of the liver that can be affected by disease.

- The cellular structure of the substance of the liver; these diseases are most commonly infectious or inflammatory and are referred to as ‘hepatitis’. Cancer of the liver cells (hepatocellular carcinoma) is relatively rare although cancers from other organs commonly spread to the liver.

- Diseases of the biliary system, which are usually inflammatory (cholangitis) or obstructive. Biliary system cancers are also rare.

- Diseases that affect the vascular supply to the liver; the most common being abnormal blood vessels that cause blood to bypass the liver (known as ‘portosystemic shunts’).

What are the signs of liver disease in dogs?

Signs of liver disease can be very variable depending on which part(s) of the liver is/are affected and whether the disease is sudden (acute) in onset or has been developing over a period of time (chronic).

Acute disease is most often seen as marked depression and inappetence, vomiting and jaundice (yellow tinge to the skin, mucous membranes and the whites of the eyes). Sometimes disorientation, apparent blindness, head pressing, seizures and blood clotting problems will occur.

Dogs with more chronic disease tend to show weight loss and loss of appetite, diarrhoea and vomiting, increased thirst and urination. Fluid will sometimes accumulate in the abdomen giving a pot-bellied appearance.

How is liver disease in dogs diagnosed?

- A variety of tests can be used to help with the diagnosis of liver disease. Analysis of blood samples are usually the first tests that are undertaken. They can be used to…

- Assess the number of liver cells that are damaged, although they do not give information about the severity of the damage, eg. alkaline phosphatase (ALP) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

- Assess how well the liver is functioning eg. dynamic bile acids, protein, bilirubin or ammonia levels

- Assess the clotting factors produced by the liver

- Look for specific infectious diseases such as canine adenovirus, toxoplasmosis or leptospirosis

- Look for specific genetic diseases such as copper storage hepatopathy in Bedlington terriers

- Liver size and architecture can be assessed using imaging such as x-rays and ultrasound. X-rays are good at illustrating overall liver size and position whereas ultrasound gives information about the internal architecture including the gall bladder, biliary system and vasculature.

Ultimately although blood samples and imaging can identify that disease is affecting the liver, understanding the disease process itself may require biopsies to be taken from the liver. These can be obtained with ultrasound guidance or surgically.

It is important to remember that the liver has a central metabolic role in the body so many non-liver diseases, such as diabetes for example, can cause secondary changes in the liver; hence wider testing may be necessary to identify the primary cause of any liver changes.

How is liver disease in dogs treated?

Treatment of liver disease will depend very much on the cause and consequences of the liver disease identified. For example, surgical intervention may be appropriate in some vascular diseases and to manage some obstructive and infectious biliary disease. In many cases, however, either the disease process has not been identified or a diagnosis has been made but no specific treatments are available, in which case symptomatic and supportive treatments are given.

In acute disease this may require hospitalisation and intensive support including fluid therapy, pain relief, management of intestinal ulceration and seizuring, assisted feeding and antibacterial cover. In chronic disease or recovering patients, supporting the liver function becomes important. Potential treatments include s-adenosyl methionine that helps the liver to deal with potentially damaging metabolic products called free radicals, antioxidants such as vitamin E, nutraceuticals such as milk thistle (silybum) and ursodeoxycholic acid – choleretics that aid bile flow and have anti-inflammatory properties. These products are often combined with dietary changes that aim to reduce liver work by moderating protein and fat intake and optimising the vitamin and mineral balance.

A variety of other drugs may also be prescribed depending on the specific condition that is being treated.

What about liver transplantation?

Liver transplantation, whilst technically possible, has only been performed for research purposes in dogs. Like all organ transplant in pets, the source of donor tissue raises many serious ethical issues.

Are some breeds of dogs at particular risk of liver disease?

Certain breeds of dog are recognised as having specific liver diseases such as copper storage disease in Bedlington and West Highland White terriers, portovascular anomalies in Irish Wolfhounds and Yorkshire terriers or idiopathic (cause unknown) chronic hepatitis in Doberman pinschers, Cocker spaniels and Labrador retrievers to name but a few.

Can I prevent my dog from getting liver disease?

Whilst we cannot prevent all liver disease, a major cause of sudden liver disease is intoxication, so by making sure your dog does not have access to medicines or chemicals around the house and keeping an eye on them whilst out to prevent scavenging, the risk van be significantly reduced. Similarly vaccination will protect against some of the infectious causes such as canine adenovirus and certain leptospira.

Fear Aggression In Dogs

by admin on June 30th, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

Fear is one of the most common triggers for threatening or aggressive behaviour in dogs. But what is fear, why do some dogs become fearful of things that won’t actually harm them and what makes some of them go to the extreme of using threat or aggression when they are feeling afraid?

Fear is one of the most common triggers for threatening or aggressive behaviour in dogs. But what is fear, why do some dogs become fearful of things that won’t actually harm them and what makes some of them go to the extreme of using threat or aggression when they are feeling afraid?

What is fear?

Fear is one of the six basic emotions seen in all mammals and is healthy, normal and desirable. It causes unpleasant feelings when a dog is around anything that may harm him, prompting him to move away from it and so protecting him from danger. However, as the saying goes ‘a life lived in fear is a life half lived’. If a dog is excessively fearful this not only interferes with doing the things he needs to do to survive, such as going out to get food and be around other dogs, but it also affects his quality of life. Dogs therefore need to learn to balance the protective benefits of fear with the need to interact with others and explore their environment. All being well, puppies learn to do this as part of their normal development during the first 12 weeks of life. They then grow up able to balance curiosity and caution in a way that keeps them safe whilst allowing them to behave in a normal way.

What can cause a dog to be fearful?

Many things influence how dogs react to whatever is going on around them. Their physical state, including their genetic drives, age, breeding cycle, illness or pain, and some medications all play a part. Dogs also start learning before they are even born and every experience they have has the potential to affect their future behavior in some way. This combination of ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’ then combines to determine how the dog reacts to new experiences. This is discussed more in the article ‘Dog Aggression’.

Most of the time these influences ensure the dog is only afraid of things that pose a genuine threat to him. However, very occasionally one or more of them will cause the dog to feel afraid of things that don’t pose a real threat, or to react excessively if they do. For example poorly socialised dogs may be fearful of other dogs even if they are being friendly, and dogs that have been physically punished in the past may become afraid of anyone raising their arm even if they are not threatening to strike the dog. Equally a dog that has been attacked by another dog in the past may escalate to using very strong aggression such as snapping or biting in response to even very mild threat from another dog.

Why do we sometimes see fear aggression in dogs?

Fear aggression in dogs only tends to arise if the dog has no other way of dealing with something that is scaring him. When they are afraid, a dog’s instinctive reaction is to get away from the trigger so the unpleasant feelings it is causing stop. If the fear is being triggered by something inanimate, such as a car or sudden noise, the dog will typically achieve this by moving away or hiding. Dogs may also try to back away or hide if they are worried by a person or another dog. However, depending on the circumstances, the dog may also try to increase the distance between themselves and a human or canine target through communication.

In most cases this will involve the use of appeasing signals. These are intended to show the target that they don’t pose a threat and to ask to be left alone. They include things like licking the lips, turning the head away and cowering.

If the target reads these signals and backs away, the dog will then stop feeling so fearful. He may also feel less fearful the next time he is in the same situation as he will know the scary person or dog will leave him alone if he asks. However, these signals don’t always work. Some dogs may still behave aggressively due to their own problem behaviour. People also often don’t recognise or respond to these signals, and things like cowering may even make some well-meaning people get closer to the dog to try and reassure them. This can inadvertently make the dog more afraid, as they feel unable to get away from the person that is scaring them.

If appeasing signals don’t work some dogs may then try using threat to make the target back away instead. Low level threat is quite subtle and includes things like leaning forward, staring at the target or holding the tail erect.

Even when this looks confident it is still often underpinned by fear and is just the dog’s way of putting on a show of false bravado to increase the chance the target will back off. As with appeasing, if this works the dog is less likely to be fearful in the same situation next time. However this strategy may also sometimes fail, for the same reasons as appeasing does, causing some dogs to then use more obvious threat such as growling or snapping. This type of behaviour is what people are often referring to when they talk about fear aggression in dogs. This escalation will very often work to make the person or other dog back off. However some dogs may retaliate and some people will punish their dog for growling or snapping at them. This can then sometimes trigger the dog to bite.

Can some dogs show threat or bite without warning?

There are occasions on which a dog may appear to use higher level threat or aggression, such as lunging, snapping and biting, without having used appeasing signals or lower level threat as a warning first. Sometimes this will be because the warnings were there but weren’t seen. We don’t very often catch bites on video but when we do we almost always see all the warning signs that the target didn’t. Dogs can also learn that lower level signals don’t work or that they result in the target retaliating or punishing them, such as if someone smacks the dog or pins him down for growling (the latter is often called an ‘alpha’ or ‘dominance’ roll). The dog then learns to skip these warnings and go straight to using very high levels of threat or even biting. The reasons behind the behaviour are still the same. All that has changed is the speed with which the dog has escalated to a bite.

What should I do if my dog shows signs of threat or aggression?

Fear aggression in dogs isn’t very common. However, if your dog is using threat or aggression out of fear then he is in distress and so not only are the people or dogs it is targeted to at risk, but your dog’s own welfare is also being compromised. It is therefore important that you seek help as soon as possible for everyone’s safety and welfare, and to prevent the behaviour deteriorating. The first step is to speak to your vet to ensure there isn’t a medical cause for his behaviour. He or she will then be able to refer you to an appropriately accredited Clinical Animal Behaviourist who can diagnose the reason for the behaviour and help you change it.

Common appeasing signals in dogs:

- Licking their nose or lips

- Chomping – like chewing a toffee

- Looking away

- Turning or leaning away

- Pulling their ears back

- Narrowing their eyes

- Sniffing or licking the other’s muzzle or face

- Cowering

- Tucking their tail (it may still be wagging)

- Walking away, or trying to escape or hide

- Rolling onto their side or back whilst avoiding eye contact

Common threat signals in dogs:

- Becoming still and tense

- Staring at the target

- Leaning forward

- Holding their tail up

- Holding their ears up and forward

- Physically controlling the other e.g. blocking their way, pinning them down or holding them using their muzzle without using pressure

- Mounting

- Putting their head over the other’s neck

- Aggressive barking

- Growling

- Snarling

- Snapping

Total Hip Replacement in Dogs

by admin on June 1st, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

Hind limb (back leg) lameness is a common reason small animal patients present to a veterinary surgeon. This is a more frequent scenario in dogs but we also see cats with this type of lameness. The causes of hind limb lameness are varied, but hip pain is a frequent reason for our patients to become lame.

Hind limb (back leg) lameness is a common reason small animal patients present to a veterinary surgeon. This is a more frequent scenario in dogs but we also see cats with this type of lameness. The causes of hind limb lameness are varied, but hip pain is a frequent reason for our patients to become lame.

What causes hip pain in dogs?

There are many causes of hip pain, however hip dysplasia, and the subsequent development of osteoarthritis, is the most common condition leading to this in dogs. This condition is also recognised in cats. In smaller dogs with hip pain, commonly terrier-type or poodle-type breeds, a condition called ‘avascular necrosis of the femoral head’ or ‘Legg Calvé Perthes disease’ can be diagnosed. Some of these patients will respond to medical therapy, but what happens if the lameness and the pain persist despite appropriate medication?

Can surgery help?

In patients where medical therapy does not control the lameness or pain, surgery can be considered. In many of these cases, the changes in the hip joint are severe and there is no chance of a corrective surgical procedure being successful. We therefore look at surgical salvage procedures to help reduce pain and ideally improve limb function. The two main surgical procedures for the hip joint are ‘femoral head and neck excision arthroplasty’ (also called femoral head ostectomy – FHO) and ‘total hip replacement’ (THR).

Femoral head and neck excision arthroplasty

Femoral head and neck excision arthroplasty is where the femoral head (the ‘ball’ part of the ball and socket joint) is removed and a false joint is allowed to form. This can reduce pain and is a reasonable treatment option. However, limb function is not always good and in one study limb function was considered poor in over 40% of cases.

Total hip replacement

Our aim should be not only to improve comfort, but also to improve limb function as best we can. This can be achieved with total hip replacement. This is where the femoral head is removed and replaced with a metal ball and the socket (the ‘acetabulum’) is replaced with a plastic cup.

This procedure has a high success rate and can improve limb function to near normal. It has historically been recommended in large dogs but we now know that smaller dogs can benefit from this procedure and the implants have been manufactured small enough to use in small breed dogs and in cats.

There are several different systems available. The main differences between the systems are whether the implants are secured with cement or not – what we term ‘cemented’ or ‘cementless’ systems.

Questions to ask if you think your dog needs a hip replacement…

Is total hip replacement the best option for my pet?

All surgical procedures carry risk and total hip replacement in dogs is no different. The complication rate is approximately 10%, so the risks of surgery need to be weighed against the potential benefits. If there is a painful lameness that is poorly responsive to medical treatment including weight control, exercise control and painkiller medication, a total hip replacement is generally indicated.

Is there a reason why my pet may not be a candidate for surgery?

Infection elsewhere in the body (skin, ear or gums) can increase the risk of infection of the total hip replacement. If surgery has been performed on the hip previously, total hip replacement may not be appropriate or can carry a higher complication risk. An immature skeleton may prevent total hip replacement from being performed although recent evidence shows this is technically possible. Maturity of the skeleton often occurs between 8-12 months. The procedure is generally expensive and cost may prohibit this surgery for some owners.

Who will be doing the surgery?

Total hip replacement is a highly skilled procedure. It should ideally be performed by a surgeon(s) with appropriate level training and good levels of experience. It is important, as a pet owner, that you are as informed as possible before making a decision to have a total hip replacement performed and the bond between a surgeon and pet owner is very important. As a pet owner in the UK, you can request to be referred to whichever clinic you wish.

Can complications occur with total hip replacement?

In short, yes. The complication rate for this procedure is generally low, meaning that a high number of patients have an uneventful recovery period. The main complications for this procedure are infection and luxation (dislocation). Other complications are rare but include fracture of the femur, sciatic nerve problems, implant loosening and embolism at the time of surgery.

What aftercare is required after total hip replacement?

Your pet will require a significant period of rest after surgery (usually several weeks) followed by gradually increasing levels of lead exercise and then off-lead activity over several months. This should be discussed with your surgeon in detail prior to surgery.

What is the prognosis for my pet?

This is a procedure which can significantly improve the life of patients with chronic hip pain. Some owners report dramatic changes in not only the way that their pet uses the limb but also in the patient’s quality of life. A good to excellent outcome is expected in most patients.

Chronic Kidney Disease in Cats

by admin on May 1st, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

‘Chronic kidney disease’ (Part 1) is a term used to refer to cats with kidney insufficiency or failure. ‘Chronic’ simply means long term. ‘Insufficiency’ or ‘failure’ means that the kidneys are no longer able to adequately perform their normal tasks. ‘Chronic kidney failure’ refers to the situation where the kidneys have not been able to perform one or more of their normal tasks adequately for a period of time (months to even years). Because the word ‘failure’ evokes such a sense of doom, we often opt for the term ‘chronic renal insufficiency’ or ‘chronic kidney disease’ instead, as many cases can be treated successfully and can look forward to months or often years of quality life.

‘Chronic kidney disease’ (Part 1) is a term used to refer to cats with kidney insufficiency or failure. ‘Chronic’ simply means long term. ‘Insufficiency’ or ‘failure’ means that the kidneys are no longer able to adequately perform their normal tasks. ‘Chronic kidney failure’ refers to the situation where the kidneys have not been able to perform one or more of their normal tasks adequately for a period of time (months to even years). Because the word ‘failure’ evokes such a sense of doom, we often opt for the term ‘chronic renal insufficiency’ or ‘chronic kidney disease’ instead, as many cases can be treated successfully and can look forward to months or often years of quality life.

What do the kidneys do?

The kidneys perform many functions in the body, including:

- helping to maintain fluid balance in the body

- producing certain hormones which stimulate red blood cell production and activate Vitamin D

- regulating blood pressure

- regulating electrolyte balance

- excreting waste products in the urine. Blood is constantly filtered through the kidneys to remove the toxic waste products of the body’s metabolism. Urine is produced in this process.

- concentrating the urine by returning water to the body, preventing dehydration

Fortunately, there is considerable ‘reserve capacity’ in the kidneys. It is well recognised that in healthy animals and humans, it is possible to remove one kidney completely without any adverse consequences due to the capacity of the other kidney to take over normal function. In fact, two thirds to three quarters of the total functioning kidney tissue (of both kidneys) has to be lost before clinical signs of chronic kidney disease develop.

How common is chronic kidney disease in cats?

Chronic kidney disease can affect any cat, of any age, any sex, and any breed. It is most commonly seen in middle to old-aged cats (those over 7 years of age), and it becomes increasingly more common with advancing age. It has been estimated that around 20-50% of cats over 15 years of age will have some degree of chronic kidney disease and it is seen more frequently in cats than in dogs.

What causes chronic kidney disease?

Most cases of chronic kidney disease are considered ‘idiopathic’ (i.e. they have an unknown underlying cause). However, some causes are well known and recognised, including:

- Polycystic Kidney Disease (an inherited disease in Persians/Persian lines where cysts replace normal kidney tissue)

- infections (also called ‘pyelonephritis’, from infection from the bladder or bacteria from blood stream, or the disease Feline Infectious Peritonitis)

- toxins (e.g. antifreeze, certain drugs)

- tumours (e.g. kidney lymphoma)

Other conditions can also gradually affect the kidneys from birth (‘congenital’ defects). Trauma, hypokalaemia (low blood potassium), and hypercalcaemia (high blood calcium) can also be contributory causes of chronic kidney disease in cats.

Intensive research is still on-going in attempt to uncover the underlying cause(s) of most cases of this disease.

If an underlying cause can be identified, this is often treated in an attempt to slow the progression of ongoing and irreversible damage to the kidneys. In most cases however, treatment is usually directed at management of the disease and the complications which arise from it.

What are the clinical signs of chronic kidney disease in cats?

‘Azotemia’ is a condition where toxins have built up in the bloodstream and can be detected on blood tests. The term ‘uraemia’ means that the patient is experiencing symptoms of poisoning from the build-up of these products in the blood stream.

Many other signs of chronic kidney disease are considered vague and non-specific—some arise from the accumulation of toxins in the blood system whilst others arise as complications from the body trying to ‘stabilise’ the disease.

Clinical signs include:

- weight loss

- poor, unkempt hair coat

- excessive drinking

- excessive urination

- nausea

- loss of appetite

- anaemia

- lethargy

- bad smelling breath (halitosis)

- high blood pressure

- (sometimes) calcification of soft tissue

How will my vet diagnose chronic kidney disease?

A diagnosis of chronic kidney disease is usually made by collecting both a blood and urine sample at the same time. There are two substances in the blood – urea and creatinine – which are commonly measured, as these are by-products of metabolism that are normally excreted by the kidneys. In chronic kidney disease, the blood concentration of these two products will increase to varying levels. There are other conditions which can also cause elevation of these substances (e.g. dehydration) and hence why a urine sample is usually assessed at the same time to assess the concentrating ability of the kidneys. Typically with chronic kidney disease, there will be increased urea and creatinine concentrations as well as poorly concentrated urine. The urine ‘specific gravity’ is a measurement of urine concentration.

Furthermore, screening blood tests may also highlight important complications which may have developed as a result of chronic kidney disease such as hypokalaemia (low blood potassium), anaemia, and hyperphosphataemia (high blood phosphate). High blood pressure is a common complication of chronic kidney disease in cats and if uncontrolled, can worsen the kidney disease. Therefore, your vet will usually want to measure your cat’s blood pressure if there are any concerns about kidney disease. Depending on the case, your vet may want to perform additional tests such as total thyroid, urine culture (to rule out kidney infection), urine protein creatinine ratio to assess if there is significant protein loss in the urine which can contribute to the progression of kidney disease, and ultrasonography to rule out kidney or ureteral stones/cysts/masses.

If there are signs of kidney disease, your vet will attempt to ‘stage’ the disease on a scale of 1-4 (‘IRIS Staging’) depending on creatinine values, urine protein to creatinine value, and blood pressure measurements, in order to facilitate treatment and monitoring of the patient and progression of disease.

Early diagnosis of chronic kidney disease in cats

Because chronic kidney disease is such a common disease in cats, routine screening of all mature and older cats (over 7 years old) can assist with early diagnosis and intervention, which in turn, may slow down the progression of disease and prolong a good quality of life. Yearly or twice yearly routine veterinary examinations are extremely important in older cats. During these examinations, your vet will check a urine sample and record your cat’s body weight. A declining urine concentration or body weight may be early signs that chronic kidney disease is developing and that further investigations should be explored.

How do you treat chronic kidney disease in cats?

It has been estimated that around 20-50% of cats over 15 years of age will have some degree of chronic kidney disease. As we spoke about above, ‘uraemia’ means that the patient is experiencing symptoms of poisoning from the build-up of toxins in the bloodstream due to the kidney disease. Our goal in treatment is to slow the progression of irreversible disease and prevent uraemic episodes which can make a cat feel unwell. Although chronic kidney disease is not a curable or reversible disease, appropriate support and treatment can both increase the quality of life, and prolong life by slowing down the progression of the disease.

The goal in early stage kidney disease patients is to postpone or even fully prevent the development of uraemia. The goal in patients in the later stages of chronic kidney disease is to resolve the uraemia and bring the patient back to an earlier stage of disease.

If a specific cause for the chronic kidney disease is identified (eg, bacterial infection of the kidneys), treatment is prescribed (e.g. antibiotics) to arrest the progression of the disease. In most cases, however, treatment is aimed at reducing the symptoms of the disease. Many cats will need to initially be put on a drip (this is known as ‘intravenous fluid therapy’) to correct dehydration and eliminate the excessive build up of toxins in the blood (similar to dialysis in humans). Once stable, treatment goals are aimed at supporting kidney function and minimising the complications of chronic kidney disease, such as the development of uraemic episodes. Despite therapy, chronic kidney disease is considered irreversible and will eventually progress over time.

Optimal management of chronic kidney disease usually requires regular monitoring by your vet, including weight checks, blood and urine tests, and blood pressure assessment, to identify any treatable complications as they arise (eg, anaemia, low potassium, high phosphate levels, urinary tract infections, and high blood pressure).

Dietary management of chronic kidney disease in cats

Cats with chronic kidney disease are more likely to become dehydrated (due to the reduced ability of the kidneys to conserve water). Maintaining a good fluid intake is therefore very important, and may help to slow progression of the disease. As cats obtain much of their water intake from their food, whenever possible, cats with chronic kidney disease should be fed tinned (or sachet) foods rather than dry foods.

An ideal diet for a cat with renal failure is a diet low in phosphate and lower in protein compared to maintenance cat diets. Saying that, protein restriction must be performed with care as too much protein restriction can be extremely detrimental to the general health of the cat. This will result in the body breaking down its own muscle to satisfy requirements, resulting in significant weight loss/poor condition and can worsen kidney disease.

Low phosphate content

Restricting the phosphate content of the diet appears very beneficial in protecting the kidneys from further damage in cats with chronic kidney disease. While restricting protein in the diet helps maintain quality of life, restricting phosphate thus appears to prolong the life of cats with chronic kidney disease. If blood phosphate concentrations remain high despite being on a low phosphate diet, further treatment with drugs known as ‘phosphate binders’, which reduce the amount of phosphate absorbed from the intestine, may also be indicated.

Other dietary measures

Other aspects of the diet may also have an important role to play in helping manage cats with chronic kidney disease. These include:

- the addition of anti-oxidants to try to protect the kidneys against further damage

- essential fatty acids to help maintain blood flow through the kidneys and reduce inflammation

- added potassium to prevent hypokalaemia (low blood potassium)

Managing the change to a new diet

Cats will often develop a strong preference for particular diets. Lower protein diets can be less palatable and therefore changing a cat’s diet with the appropriate therapeutic diet can be challenging. These tips may help:

- Always make gradual changes over a period of 1-2 weeks, especially if your cat is considered ‘fussy’

- Only increase the amount of the new food once your cat is happy to eat the old mixture

- Warming the food to body temperature may help increase the palatability and stimulate appetite with the released aroma

In most cases, with sufficient care and time, cats can be very successfully transitioned to a new diet, and as this is such an important part of managing chronic kidney disease it is worth taking the time to do this properly.

If cats absolutely refuse to eat any of a new diet, it is important that they eat something, so keep offering their old diet in this situation and contact your vet for further advice.

Managing dehydration

Using a wet rather than a dry diet is important to increase water intake in cats with chronic kidney disease. However, they sometimes still do not consume enough water to compensate for what is being lost in the urine. In these cases, make sure a good supply of fresh water is always available, and cats should be encouraged to drink by offering several watering stations around the house (pint glasses filled with water are always useful!). Using flavoured waters (chicken, tuna spring water – not brine!) or water fountains can encourage drinking. Using intermittent intravenous fluid therapy at your vet clinic may be required every few months. Your vet can also teach you how to administer intermittent subcutaneous fluid therapy in the home environment.

Phosphate binders

If, despite using a low phosphate diet, blood phosphate levels remain high, using a phosphate binder added to the diet may be required. This is important, as controlling blood phosphate levels appears to have a good protective effect on the kidneys in cats with chronic kidney disease.

Potassium supplementation

Some cats with chronic kidney disease will also develop low blood potassium levels. This can cause muscle weakness, can contribute to poor appetite and itself can worsen chronic kidney disease. Where this is identified, potassium supplementation (usually in the form of tablets, gel or powder added to the diet) would be required.

Controlling blood pressure

Cats with chronic kidney disease are at risk of developing high blood pressure and this can have a number of damaging effects including acute blindness/blood accumulation in eyes, strain on heart muscle, and worsening of the kidney disease. Blood pressure should ideally be monitored in all cats with chronic kidney disease and can be treated with medication if diagnosed.

Treatment of anaemia

In advanced chronic kidney disease, anaemia can be quite common and is due to the lack of production of a hormone by the kidneys called erythropoeitin. This hormone stimulates the bone marrow to make red blood cells. Anaemia can also result from blood loss from the intestines due to the effects of toxins on the stomach lining. Severe anaemia may lead to lethargy and weakness and result in poor quality of life. Depending on the underlying cause, and severity, a variety of options may be available to alleviate the effects of anemia including iron supplementation, management of stomach ulceration, and the administration of erythropoietin to stimulate the bone marrow.

Treatment of nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are more common in advanced chronic kidney disease and can cause poor appetite and significantly affect a cat’s quality of life. Various drugs can be used to control these signs.

Use of ‘ACE inhibitors’ and ARBs (Angiotensin Receptor Blockers)

Blocking the activation of a hormone known as ‘angiotensin’ may be of benefit in chronic kidney disease in cats. This can be achieved by using so called ‘ACE-inhibitors’ (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors), or using angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

Drugs such as ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers can benefit cats with chronic kidney disease by dilating blood vessels and supporting blood flow through the kidneys, lowering blood pressure, and also significantly reducing protein loss through the kidneys which can lead to the progression of disease, and so potentially improve survival in these patients.

What is the prognosis for cats with chronic kidney disease?

Because chronic kidney disease is usually progressive over time, it will eventually lead to the need for euthanasia once it has reached ‘end stage’ with recurrent uraemic episodes. However, the rate of progression of kidney disease will vary considerably between individual cats. With appropriate support and treatment, quality of life can be improved and progression of the disease slowed down. Therefore the long term prognosis will greatly depend on the stage/severity of the disease and the underlying cause in each individual patient and your vet will be able to discuss this with you.

Disc Disease in Dogs

by on April 2nd, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

Dachshunds and similar breeds such Pekingese, Lhasa Apsos and Shih Tzus, have short legs and a relatively long back. These breeds suffer from a condition called ‘chondrodystropic dwarfism’. As a result they can be prone to back problems, more specifically disc disease.

Dachshunds and similar breeds such Pekingese, Lhasa Apsos and Shih Tzus, have short legs and a relatively long back. These breeds suffer from a condition called ‘chondrodystropic dwarfism’. As a result they can be prone to back problems, more specifically disc disease.

What are intervertebral discs?

The intervertebral disc is a structure that sits between the bones in the back (the vertebra) and acts as a shock absorber. The structure of a disc is a little like a jam doughnut with a tough fibrous outer layer (annulus fibrosus) like the dough, and a liquid/jelly inner layer (nucleus pulposus) like the jam.

In chondrodystrophoid breeds like dachshunds, the discs undergo change where the nucleus pulposus changes from a jelly-like substance into cartilage. Sometimes the cartilage can mineralise and become more like bone and show up on an x-ray. In these breeds, this change occurs in all discs from approximately one year of age and is considered part of usual development for these dogs. This change in the discs is a degenerative process and predisposes the disc to disease.

The most common type of disc disease in dachshunds and other chondrodystrophoid breeds is ‘extrusion’. This is where the annulus fibrosus ruptures and allows the leakage of the nucleus pulposus into the spinal canal. An analogy we often use is the jam leaking from a jam doughnut when it is squeezed.

What are the signs of disc disease in dachshunds and other breeds?

The first evidence that there might be a problem is that your dog may be in pain. This may consist of yelping and/or a hunched back and more subtle signs such as quietness and inappetence (lack of appetite). Back pain is commonly mistaken for abdominal pain.

After pain there may be mobility problems. The first thing to occur is wobbliness of the hind limbs – termed ‘ataxia’. After this, weakness can develop with the wobbliness, which is termed paresis. Subsequently, the patient may lose control of the back legs altogether and not be able to walk. If there is no movement in the hind limbs this is ‘paralysis’.

Will my dog need to be referred to a specialist?

Spinal disease can sometimes be difficult to manage and your dog may be referred to a specialist. At the referral clinic, your dog will be assessed by the specialist neurologist or neurosurgeon. They will test various reflexes to decide where they think the issue may be. They will perform a clinical examination which will assess for other disease processes and look for any areas of pain. One thing that is important to assess is the presence of pain sensation. We call this ‘deep pain sensation’. To assess this, the specialist will pinch your dog’s toes, usually with fingers initially but it may need to be with forceps. This is not a pleasant test to perform but it is necessary as the presence of deep pain comes with a more favourable prognosis. The loss of deep pain sensation means the prognosis is worse and without surgery is considered very poor.

What investigations will be performed?

After the clinical examination, we will generally have a good idea where the problem is and the next step is to confirm the diagnosis. The best way of diagnosing disc disease is with MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CT (computed tomography). With MRI we get detailed information about the soft tissue such as the disc itself and the spinal cord. Computed tomography uses the same technology as x-ray and provides good information about the bone and mineral structures and can tell us where the lesion is and whether or not surgery is indicated.

How is disc extrusion treated?

If a disc extrusion – the ‘jam out of the doughnut’ scenario – is diagnosed then we can opt for conservative care or surgical management.

Conservative care is a non-surgical management and can be considered in dogs where the signs are mild or intermittent and when there is only mild compression of the spinal cord. It can also be considered if there are concerns regarding the cost of surgery.

Surgical treatment involves making a window through the bone structures of the vertebra, into the spinal canal, a procedure called a ‘hemilaminectomy’. Once into the spinal canal, the disc material (nucleus pulposus) is removed and the spinal cord is decompressed. Surgical treatment tends to give a speedier and more predictable recovery and is often considered the treatment of choice, where indicated.

What is the prognosis for a dog with disc disease?

When dealing with spinal injury, particularly from disc disease, we aim for patients to achieve a functional recovery. This means the patient is pain free, is able to get around on their own (although they may still be wobbly) and able to toilet themselves unaided. Whether a patient will return to normal or whether there will be residual deficits is down to the individual.

The prognosis for patients who have intact deep pain sensation is favourable, with most patients (80-90%) achieving a functional recovery. In patients without deep pain sensation, the prognosis is guarded, with only 50% of cases achieving a functional recovery but without surgery the prognosis for a functional recovery is approximately 5%.

Surgery tends to speed recovery and aid early pain control. We expect most patients to recover within the first 2 weeks after surgery, with a smaller number of patients taking longer (2-6 weeks). If there is no improvement after 6 weeks the prognosis becomes more uncertain and long term disability may be present. This occurs in approximately 1 in 10 patients.

Inappropriate Urination in Cats

by on March 5th, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

Urination in cats – when does it become a problem?

Urination in cats – when does it become a problem?

- The perceived threat of a neighbouring cat

- The appearance and stress of a newly introduced kitten or human baby

- Negative associations with the litter tray

- The pain of urination

- A change in litter type

Head Tilt in Dogs

by on January 30th, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

What Does it Mean if My Dog has a Head Tilt?

What Does it Mean if My Dog has a Head Tilt?

- Infections

- Polyps

- Reactions to topical drops or solutions if the ear drum is damaged

- Hits to the head

- (Occasionally) ear tumours

- (Rarely) a genetic abnormality affecting puppies, especially those of the Doberman breed

- Idiopathic vestibular disease

- Tumours

- Trauma

- Inflammation

- Stroke

- Rarely, similar signs can be seen in dogs that are receiving a specific antibiotic called metronidazole. Recovery will often take place within days of stopping this medication.

Winter Coughs – Be prepared

by on January 5th, 2015

Category: News, Tags:

We have seen a surprising number of coughing dogs over the last few weeks all caused by a contagious form of infectious tracheobronchitis otherwise know as Kennel Cough – an unfortunate name as you do not need to be in kennels to catch it!

These infectious coughs, very similar to what we can catch, are caused by a strain of doggy flu (parainfluenza) and a bacteria called Bordetella bronchiseptica working together.

This infection can be vaccinated against with a few droplets up a nostril. This vaccination needs boosting annually to keep protection as high as possible.

Kennel cough usually presents as a harsh honking cough, often with the poor dog retching at the end. This is due to coughing with such force that the windpipe collapses trigging the gag reflex. Understandably many people worry that their dog initially is choking with something stuck in their throats.

These germs are extremely contagious, every time a dog coughs it releases thousands of infectious droplets which can survive in the environment and even on our clothes! Infected dogs should be rested and isolated until the cough has gone. This can mean your dog is not allowed to go for a walk for some weeks!

Just like our human flu vaccinations, kennel cough vaccines can never give 100% protection but will often manage to reduce the severity of signs and duration of signs if any new strains emerge.

If your dog is walked in busy parks or is likely to be mixing with other dogs, either in kennels or with a dog walker, we would definitely recommend vaccinating against Kennel Cough. As always if you are at all worried about your dog or not sure of his/her vaccination status then please contact the surgery for advice.

Dry Eye

by on December 3rd, 2014

Category: News, Tags:

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), commonly referred to as “Dry Eye”, is one of the most common dog eye problems. Dry Eye affects 1 in every 22 dogs.

Dry Eye is caused by destruction of the tear glands by the dog’s immune system. This means that too few natural tears are produced. Damage to the tear glands is irreversible. If left untreated, eventually the tear glands are completely destroyed and the dog loses the ability to produce tears. Dry Eye is a painful condition, and ultimately leads to permanent blindness.

Natural tears have many important functions which are lost in Dry Eye: they carry vital nutrients and oxygen, lubricate and cleanse the eye, and help protect against infection. Without tears, the eye becomes very dry and uncomfortable. Conjunctivitis, eye infections and ulcers become more common and discharge may be seen from the eyes. New blood vessels start to grow on the surface of the eye and dark pigmentation may develop. Eventually these changes lead to permanent blindness. It is very important to diagnose Dry Eye early, before these undesirable changes become severe and much of the tear tissue is destroyed.

It is important to recognize that in the vast majority of cases, Dry Eye is a lifelong condition and requires lifelong treatment. If not treated correctly, the dog will experience discomfort and the disease will affect its sight and welfare long term.

Dry Eye has a very variable appearance, so it is not possible to diagnose the condition just by looking at it. Fortunately there is a quick and simple test to diagnose Dry Eye, and with correct treatment the condition can be managed successfully long term.

Dry eye can affect all breeds at any age, so it is important to be aware of the signs to look out for.

Signs of Dry Eye

The appearance of Dry Eye can be quite varied and subtle, especially early in the disease. It is better for the health of the dog’s eyes to pick up the problem early, so that more tear tissue remains and fewer abnormal changes to the eyes develop. The earlier the problem is diagnosed and treated, the better the long term outlook for the dog’s eyes.

We recommend testing virtually all sore eyes for Dry Eye, to make sure the condition is diagnosed as early as possible.

If your dog has any of the following signs, you should make an appointment with your veterinarian. Remember to tell your veterinarian if your dog has experienced any previous eye problems.

Signs to look out for

- Uncomfortable eyes – your dog may blink excessively, rub its eyes or try to keep its eyes closed

- Eyes red and inflamed

- Discharge from the eyes

- Dry looking eyes

- Frequent conjunctivitis, eye infections or corneal ulcers

- Dark pigment on the surface of the eyes

- Prominent blood vessels on the surface of the eyes

As dogs with Dry Eye are prone to getting eye infections and conjunctivitis, we recommend testing for Dry Eye in all dogs that have had more than one eye infection in any 12-month period. Otherwise, Dry Eye could be missed and the dog only treated for the infection, and not the ongoing underlying problem.

Diagnosing Dry Eye

Diagnosis of Dry Eye is quick and simple – the test only takes 60 seconds. Your veterinarian probably already tests most dogs with eye problems as well as predisposed breeds routinely.

Your veterinarian measures tear production in dogs using a Schirmer tear test (STT). The STT involves placing a special strip of paper in the eye to assess tear production. Usually the tear production in both eyes is tested as the results are often quite different. The test will not cause your dog any discomfort and does not require sedation or anesthesia. The results of this test are available are immediately. The results of the test are interpreted along with other findings, such as clinical signs, to determine whether KCS is present. If your dog has Dry Eye, it is not producing sufficient tears and should be started on treatment immediately.

Breeds affected by Dry Eye

Dry Eye is very common – 1 in every 22 dogs are affected by this disease. However, in certain breeds, this figure is almost doubled. It is important to be aware that the eyes of some dogs affected by Dry Eye look quite normal, despite severely reduced tear production and destruction of the tear glands. The sooner Dry Eye is diagnosed and the correct treatment started, the better the long term outlook for the dog’s eyes. Dry Eye is also painful (a bit like having grit in your eyes) so prompt treatment will also improve the welfare of the dog.

Predisposed Breeds

All breeds of dogs can develop Dry Eye at any age, but some are more prone to the condition. Breeds of dog particularly susceptible to Dry Eye include:

English Cocker spaniel

West Highland White terrier

Cavalier King Charles spaniel

Shih-Tzu

Other breeds include the Yorkshire terrier, Bulldog, Pekingese, Pug and Lhasa Apso.

We recommend testing susceptible breeds regularly and many owners elect to have their dog tested during a routine appointment, such as for vaccination. This ensures that Dry Eye is picked up early and treatment started before too much tear gland tissue is destroyed.

Diagnosis of Dry Eye is quick and simple – the test only takes 60 seconds and involves placing a special strip of paper in the eye to assess tear production.

Call us today to make an appointment.