News

Archive for the ‘News’ Category

What is a Heart Murmur?

by admin on March 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

Hearing your vet announce that “your pet has a heart murmur” can be very daunting. However, the significance of a murmur very much depends upon the situation. Just as a fever can be something or nothing, a murmur may be similar – it may be insignificant, but it could also be a symptom of a disease that requires treatment. So, first of all, what is a heart murmur?

Simply put, a murmur is a sound produced by a squirt of blood inside the heart when it pumps. There are many causes of a murmur.

There are three sections in this information sheet:

- Murmurs explained

- FAQs about murmurs

- List of the common causes of murmurs in dogs and cats

1. Murmurs explained

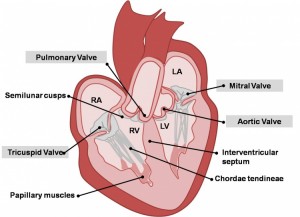

Murmurs due to regurgitation

Each of the four valves in the heart act as non-return valves, permitting blood flow in one direction (forwards). If a valve becomes faulty and no longer prevents backflow, then there is a resultant backward squirt of blood through the gaps in the valve with each heartbeat. This backward squirt of flow through an incompetent valve results in an abnormal heart sound called a heart murmur. A murmur thus sounds like a ‘squirting’ or ‘gushing’ sound during each heartbeat. The most common cause of an incompetent valve in older dogs is Mitral Valve Disease, or Endocardiosis, as it is also known.

Murmurs due to narrowed valves

If a heart valve is abnormally narrowed, usually due to a congenital defect (eg. Aortic Stenosis or Pulmonic Stenosis) then blood flow pumped out through the narrowed valve is pinched, resulting in an abnormal squirt of flow, ie. a murmur. This can be likened to putting a thumb over the end of a hose pipe to make the water squirt, rather than pour.

Murmurs due to ‘holes in the heart’

A murmur can also occur through a hole in the heart – the murmur is caused by the squirt of blood going through the hole. A hole between the left ventricle and right ventricle results in a squirt of blood being pushed through the hole when the heart ventricles pump (this is called a Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)). A hole between the aorta and pulmonary artery (the two major arteries leaving the heart) results in blood squirting through the hole (this is called a Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)).

Puppy murmurs

In puppies less than 6 months of age, in addition to murmurs produced by congenital defects, puppies can have innocent or benign murmurs – often called a puppy murmur. These occur due the fast flow of blood in such a small heart. As the puppy and its heart grow and mature, then the murmur gradually disappears. It is virtually impossible for a vet to discern the difference between a puppy murmur and a congenital defect. If a murmur persists beyond 6 months of age, it is more likely to be a congenital defect.

Murmurs associated with illness

A murmur can also be produced when a dog is anaemic and the blood thin. In this situation, thinner blood (less viscous) results in a faster speed of flow and thus a murmur. A similar situation can occur when a dog is ill for other reasons, such as during a fever.

2. FAQs about heart murmurs in cats and dogs

What is the significance of a murmur?

This depends upon what the cause of the murmur is from the list above, whether the defect causing the murmur is classified as: mild, moderate or severe, and whether it is resulting in heart enlargement or not.

Is the loudness of a murmur significant?

Not always. It depends upon what the cause of the murmur is from the list above. Some murmurs are innocent and of no clinical significance, whereas others are associated with defects. Many defects can be mild and have no effect on the heart and animals can live a full and normal life with them, whereas other defects affect the heart and may need some form of treatment.

Do all these murmurs sound different for each defect?

No, in fact they virtually all sound the same. The squirt (murmur) is heard when the heart beats, so the murmur is brief. The only defect that produces a slightly different sound is a PDA – the murmur is continuous rather than intermittent or brief.

Listening with a stethoscope is not easy and many vets find this difficult. As humans, we all have differing skills and abilities, so there is a lot of variation. It is likely that a veterinary cardiologist will hear murmurs better, because they have had a lot more practice and experience, as well as additional training.

What is the best way to diagnose a murmur?

Nearly always, an ultrasound scan (echocardiography) is the best way to diagnose a murmur. But sometimes additional tests are also required, such as chest x-rays, ECG or blood tests. Echocardiography is a difficult and skilled examination that is best performed by an experienced clinician.

3. List of the common causes of murmurs in dogs and cats

Defects can be congenital, meaning an animal has been born with the defect. Or there can be changes in the heart that develop in adult life, for example due to ageing degeneration of a valve.

Murmur due to Mitral Valve Regurgitation:

- Mitral Valve Disease (MVD) is the most common cause of a murmur in adult dogs in older age

- Mitral Valve Dysplasia is a congenital defect of the valve

- Mitral Valve Regurgitation can occur secondary to heart enlargement of other causes in dogs

- Mitral Valve Regurgitation can be secondary to cardiomyopathy in cats

Murmur due to Aortic Valve Stenosis:

- Subaortic Stenosis and Valvular Aortic Stenosis is a congenital defect of the valve

- Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in cats, often causes ‘Subaortic- like Stenosis’

Murmur due to Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation:

- Tricuspid Valve Disease occurs in adult dogs in older age, most will also have MVD

- Tricuspid Valve Dysplasia is a congenital defect of the valve

- Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation can occur secondary to Pulmonary Hypertension

- Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation can be secondary to heart enlargement of other causes

- Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation, when mild, can be seen in some normal dogs

Murmur due to Pulmonic Valve Stenosis:

- Valvular Pulmonic Stenosis is a congenital defect of the valve

Murmurs associated with holes in the heart:

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus is a congenital defect resulting in abnormal flow between the aorta and pulmonary artery

- Ventricular Septal Defect is a congenital defect in which there is a hole between the two ventricles

Innocent murmurs

These are murmurs due to abnormal flow within the heart and not due to a defect in the heart, ie. there is no congenital defect or degenerative disease. There are a number of causes, these are just some examples:

- Puppy murmurs are innocent murmurs that usually disappear by 4-6 months of age

- Anaemic murmurs are due to the blood being thin

- Fever murmurs are due to turbulence in blood flow

- Flow murmurs are seen in some athletically fit dogs, ie. a murmur with no defect present

Lens Luxation

by admin on February 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

What is the lens?

The lens is a large transparent structure within the eye lying just behind the black part of the eye (the pupil). The lens helps to focus light onto the back of the eye. It is normally held in place by tiny threads all around its edge.

What happens in lens luxation?

In patients suffering from lens luxation (dislocation), the lens shifts out of position and moves either into the front or into the back of the eye. If the lens becomes trapped in the front of the eye, it can cause water-logging of the window of the eye (seen as blueing of the front of the eye) and an increase in pressure within the eye (glaucoma). If it falls into the back of the eye, the lens can damage the sensitive tissue at the back of the eye (the retina) and cause it to loosen (retinal detachment). This can also lead to glaucoma. In both cases, the eye is usually painful, and blindness develops unless early appropriate treatment is given.

What causes lens luxation?

Many cases of lens luxation are hereditary and caused by a weakness in the threads holding the lens in place. This condition is called primary lens luxation and is common in the Jack Russell and other terriers. It is also occasionally seen in other breeds and crossbreeds.

Some cases of lens luxation are due to other eye diseases such as cataracts, inflammation within the eye or chronically increased intraocular pressure (glaucoma). These diseases cause damage to the threads that hold the lens in place and as a result it eventually comes loose.

What are the signs of lens luxation?

In most cases of primary lens luxation, the disease develops very rapidly. In the very early stages the eye may just look slightly red and sore. These signs may be misinterpreted as simple conjunctivitis but are in fact the beginning of a potentially blinding disease. Later the patient is often depressed and reluctant to exercise.

The eye usually appears red and painful, often with a bluish tinge over the cornea. As the pressure in the eye goes up, the optic nerve at the back of the eye (which takes messages from the back of the eye to the brain) becomes damaged and blindness results.

How is lens luxation diagnosed?

Once the lens completely dislocates it is relatively straightforward to see that it is out of position in most patients. In addition, examination by an ophthalmic specialist using specialised equipment may enable a diagnosis of lens luxation to be made well before the lens actually dislocates out of position.

Is treatment possible?

Lens luxation is a serious, blinding painful condition. Although medical management of primary lens luxation is an option, in most cases surgical removal of the lens is likely to give the best chance of preserving vision. Lens removal may also be indicated if the lens has luxated as the result of other eye conditions, but each of these cases must be assessed on their individual merits.

The surgical removal of a luxated lens is an operation that should only be carried out by an eye specialist as it requires special training and skills, the use of an operating microscope and microsurgical instrumentation. The surgery also requires the use of a special muscle-relaxant anaesthetic, as the eye must be held absolutely still in the right position during the operation. During the procedure the patient’s breathing is taken over by the anaesthetist. Again, specially trained staff are required to monitor this anaesthetic.

In surgery for lens luxation, the cornea, which forms the clear window at the front of the eye, is incised and the luxated lens is gently removed. The inside of the eye is coated with special gel during the procedure to help to protect its delicate structures. Some of the natural jelly at the back of the eye (the vitreous) also needs to be removed during the operation, and this is performed using highly specialised mechanised equipment. The wound is stitched with suture material finer than a hair. The stitches dissolve over a period of weeks after the surgery.

Following surgery, intensive medical treatment is required, and several re-examinations are necessary to give the best chance of a successful outcome.

Will my pet cope without a lens?

Most pets cope well without a lens but will need a while to adapt to the new vision. Most dogs without lenses are able to avoid bumping into objects, and many can still chase a ball.

Success chances and possible complications

The chance of a successful outcome depends in part upon the duration of the problem prior to presentation and also whether the lens is completely dislocated at the time of surgery. In early cases, the outcome of surgery can be very satisfactory, but in longstanding cases, the success chances are significantly reduced.

Unfortunately, blinding complications are seen in a significant percentage of cases – up to 30% or 40% depending upon the condition of the eye and duration of the problem by the time of surgery. These complications include persistence of glaucoma, bleeding into the eye and retinal detachment.

Even after successful surgery which has saved vision, it may be necessary to continue with long-term medication, especially to keep the pressure in the eye under control. This may in turn require patients to be returned for check-ups from time to time.

Does the condition affect both eyes?

Yes, unfortunately, primary lens luxation affects both eyes, although not necessarily at the same time. However, there will often be early signs of partial dislocation of the lens in the second eye at the time that the first eye is noticed to have a problem. Without treatment, the second lens will then usually dislocate within a few months of the first, and the natural progression of patients with this condition without surgery is to become blind in both eyes. Glaucoma then usually develops, and this not infrequently means that one or both eyes may need to be removed in order to relieve pain.

Is preventative treatment available for the second eye?

Yes, especially in cases of primary lens luxation. If the earliest signs of lens instability (subluxation) are detected at the time that the first eye is affected then the lens may be surgically removed. Early removal of unstable lenses carries the best chance of long-term success. In early cases, it may be possible to perform the surgery through a smaller incision using specialised equipment, and this, in turn, helps to give a better prognosis.

What happens if vision is irreversibly lost in an eye with a luxated lens?

Eyes that have lost vision irreversibly due to lens luxation are not suitable for lens removal. Because many eyes with lens luxation are painful, it may be necessary to consider removal of the eye under these circumstances.

What happens if an eye needs to be removed?

Eye removal is generally only recommended if the eye is painful and blind and the pain cannot be readily controlled with medication. The thought of an eye being removed may be alarming at first, but it is important to realise that this will generally make the patient feel much more comfortable and much happier very quickly. The hair is clipped at the site of the operation but soon grows back, and this then leaves hairy skin where the eye used to be. There is no hole left behind, and the result is cosmetically perfectly acceptable. And of course our patients don’t look at themselves in the mirror and worry about their appearance, they just feel more comfortable and get on with life!

Cystitis in Cats

by admin on December 6th, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What is special about cystitis in cats?

Unlike dogs and people, cystitis in cats is frequently caused by stress rather than by an infection.

Whilst cystitis in female cats is painful and upsetting, it can actually turn into a life-threatening condition in tom cats if the urethra (the way out of the bladder) is blocked up by swelling, blood clots or crystals. Those cats are absolutely unable to pass urine, which leads to the bladder overfilling. This in turn causes back-pressure which can ultimately lead to kidney failure and collapse. Any male cat that seems unable to pass urine should be seen by a veterinary surgeon immediately.

Why do cats get cystitis?

There are a number of possible causes of cystitis, but the majority of young cats which develop cystitis do so as a result of stress. Sometimes an obvious reason for the underlying stress can be identified, such as the house being decorated or another cat or a dog moving in, but often it is difficult to recognise the actual cause of the stress. Once cats have developed this type of cystitis, they are very prone to having further bouts of it in the future and in some cases management of some variety is necessary to prevent further episodes.

A smaller proportion of cats, especially elderly individuals or those with chronic problems, such as kidney disease, develop cystitis due to infection, generally by bacteria.

There are several other reasons why cystitis may develop, and these include bladder stones, tumours or toxic cystitis. Such cases are uncommon, however.

What are the clinical signs of cystitis?

All types of cystitis have similar clinical signs, not all of which are necessarily observed in every case:

- Frequent visits to the litter tray

- Passing very small amounts of urine on the litter tray or even being unable to pass anything at all

- Accidents in the house or urination in inappropriate places

- Bloody urine

- Painful urination – some cats cry when urinating

- Some cats are restless or seem off colour

How is the disease diagnosed?

The clinical signs are very often already suggestive of cystitis. To rule out other causes and to identify which type of cystitis is affecting your cat, a general physical examination and also further tests, such as a urine analysis, are usually necessary. In some cases blood tests, radiographs/ultrasound examination or other tests may be required, too.

A male cat that is unable to urinate due to complete blockage of the bladder needs to be treated as an emergency.

How is cystitis in cats treated?

If stress-related cystitis is diagnosed, the treatment usually consists of pain relief, relaxation of the cramped bladder muscle and glucosamines, which seemed to soothe the sore inside layer of the bladder. We also strongly advise that cats which are prone to cystitis are fed only on wet food. This is an exception to the general rule, as we usually recommend feeding cats and dogs on dry food. However, we know that the overall water intake for the patient is better when wet food is given, and a slightly more dilute urine can help to prevent further episodes of cystitis. If possible, small amounts of water can be added to the wet food or the cat may be encouraged to drink by flavouring the drinking water with small amounts of something tasty e.g. salt-free chicken broth or tuna. Anything that increases the water intake in such cats is beneficial.

Male cats that are unable to pass urine often need much more intensive treatment. Usually such patients need an emergency general anaesthetic to allow us to unblock the bladder and achieve urine flow. In some cases, especially if the problem has been overlooked for a little while, intensive care may be necessary for several days and unfortunately not all cats with this condition manage to pull through. The earlier the condition is treated, the better.

My cat has cystitis – what is the outlook?

While some cats only ever have one episode of cystitis in their life, once a cat has developed stress-related cystitis he or she is prone to develop further episodes when stressed. It is advisable always to feed such cats on wet food and encourage drinking as much as possible. It is also important to monitor such cats closely – this applies especially to tom cats as they are prone to becoming blocked. In some cases ongoing management or medication is required.

Can dogs get this type of cystitis?

Dogs do not get the stress-related type of cystitis which we see in cats. They certainly can develop cystitis, but it is usually due to an infection or other underlying cause. The signs of cystitis in dogs are similar to those in cats (see above), and if you become aware of such symptoms, you should seek veterinary advice at an early stage.

Zoonoses

by admin on December 2nd, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What is a zoonosis?

A zoonosis is a disease which can be passed between animals and humans.

The following information sheet is designed to give an overview of some common or important diseases which can be passed from cats and dogs to humans, however, the list is not exhaustive. Conditions which can be passed to humans from other domestic or exotic species are not included. In general, these diseases are of most significance to immuno-compromised people.

What does immuno-compromised mean?

People who are immuno-compromised have immune systems which may not work very well. This group would include the very old and very young, people recovering from severe illness or surgery, people with AIDS/HIV and people on chemotherapy drugs.

What skin diseases can be caught from cats and dogs?

Humans can be bitten by cat and dog fleas. The bites are seen as small, red, itchy lumps very often on the lower legs/ankles. It is important to keep cats and dogs regularly treated for fleas using a veterinary prescribed flea treatment. If humans are being bitten it is likely that the environment is infested, so the whole home should be treated as well. Make sure you follow any care and safety instructions when you spray your home.

Ringworm (dermatophytosis) is not a worm at all but a fungal infection of the skin. Many species of animals can carry this infection. It is often seen as patches of hair loss and scaling of the skin on cats and occasionally dogs. When humans pick up ringworm they develop red and often circular patches on their skin. This condition is treatable for both humans and pets.

Humans can also become irritated by mites that they acquire from their pets e.g. ‘fox mange’ (Sarcoptes scabei) and ‘walking dandruff’ (Cheyletiella). Infections in humans are usually self-limiting but it is advisable to visit the doctor. Cats and dogs can be treated under veterinary care after diagnosis in their owners.

Can worms affect humans?

We strongly recommend that pet cats and dogs are regularly wormed. Cat worms are currently not thought to cause problems for human health but we are not certain about this. Toxocara canis is a common round worm of dogs. If children are infected by this worm, the larva can occasionally ‘get lost’ on migration within the body and cause damage to the eyes, brain and elsewhere. Monthly worming of dogs with a good quality round wormer will prevent dogs becoming infected and spreading the worm.

Echinococcus granulosus is a dog tapeworm which also causes problems when larva ‘get lost’ on migration in the body, but this worm is thankfully only found in limited habitats (certain areas of Wales and the Hebrides). Hookworms (Ancyclostoma) which are passed occasionally in dog faeces can cause skin irritation when people have close contact with contaminated soil. Fortunately the condition is easily treated.

My pet has a tummy up-set can I catch anything from it?

Hand washing and basic hygiene should always be used when clearing up after a pet, especially when they have vomiting or diarrhoea. Giardia, Campylobacter, Salmonella and E. coli are just some of the infections which may be passed on to humans. If these bugs are suspected we will test for them but sometimes infections are not obvious, so care should always be taken in clearing up pets’ faeces.

I am pregnant, are there any specific zoonoses I should be concerned about?

Toxoplasmosis is of particular concern for pregnant women. This is a common single-cell parasite which only causes mild flu-like symptoms in most affected people – however, it can be critical to the health of both mother and fetus if a pregnant woman is infected. Many species of animal can be affected by toxoplasmosis, but only cats, the primary host, can spread the disease. When the spores pass out of the cat in its feces they are inactive. It takes about 24 hours of contact with air for the spores to become active or infective. This means that direct handling of an animal is not a great hazard, but pregnant women should not handle cat faeces or the litter tray. The greatest risk factors for Toxoplasmosis are gardening (i.e. handling soil), unwashed fruit and vegetables as well as undercooked meat. However, it is always recommended that pregnant women are especially careful to wash their hands after touching animals and before handling food. If you have any concerns about zoonoses during pregnancy you should discuss these with your midwife or doctor.

Can I catch Weil’s disease from my dog?

Weil’s disease is the severe human form of leptospirosis. This is an uncommon disease in humans and it is very rare for it to be passed by pet dogs. However, if a dog is affected its urine can be infective to humans. Both dogs and humans most commonly catch leptospirosis from stagnant or slow-moving water (specifically that which has been contaminated with rat urine). The disease causes sudden kidney and liver failure. We strongly recommend that dogs are vaccinated against leptospirosis annually. Care should be taken when handling dogs’ urine and, if leptospirosis is suspected, handlers should wash their hands and ideally wear gloves.

What should I do if I am scratched or bitten?

Cat and dog bites can be very serious. Wash all bites liberally under running water and always seek medical advice from your doctor as antibiotics are often required. There may also be legal implications if a dog has bitten a person – please see the UK Government website.

Cat scratches can also be nasty. All scratches should be thoroughly washed. Any scratch which becomes inflamed or painful should prompt a visit to a doctor. There is a bacterium which some cats have in their saliva and on their claws called Bartonella henselae which causes ‘cat scratch disease’ in humans – symptoms include swelling at the site of infection, fever, and swollen glands. Treatment may be required, especially in immuno-compromised patients.

If you have any queries concerns about your dog or cat and Zoonoses, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Lymphoma in Dogs

by admin on November 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What is lymphoma?

Lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is, amongst other things, involved in immunity and fighting infections. Lymphoma arises from cells in the lymphatic system called lymphocytes which normally travel around the body, so this form of cancer is usually widespread. Lymph nodes (sometimes called lymph glands) are part of the lymphatic system and are located all over the body. Lymphoma can affect some or all of the lymph nodes at the same time. It may be possible to feel or see affected lymph nodes that are near the body surface (as shown in the picture) – they usually feel big and firm. Lymph nodes deeper inside the body are also often involved, as well as internal organs such as the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. This widespread involvement is not like tumour spread in other types of cancer.

Lymph nodes you can feel:

1 Submandibular: under the jaw

2 Prescapular: in front of the shoulder

3 Axillary: in the armpit

4 Inguinal: in the groin

5 Popliteal: behind the knee

What tests will my dog have?

The diagnosis of lymphoma is usually confirmed by taking a sample from a lymph node, either by fine needle aspirate or biopsy. Fine needle aspirate of a superficial lymph node is a quick, simple procedure using a needle (similar to those used for booster injections) to collect cells from the node. It causes minimal discomfort and is normally carried out while a patient is awake or under mild sedation. In some cases we need to take a biopsy, involving the removal of a larger sample of tissue – this may be carried out under a general anaesthetic. These tests allow a very accurate assessment of the tumour by a specialist looking at the samples under a microscope.

To allow evaluation of internal lymph nodes and organs, patients usually have X-rays and an ultrasound scan. Mild sedation is usually required for these procedures, as we need our patients to be very still. Blood sampling is also performed to assess a patient’s general health status.

In some cases we will recommend taking samples of bone marrow to investigate whether or not cancer cells are present in the bone marrow. This procedure is carried out under a short general anaesthetic.

All the diagnostic information we obtain allows us to give an accurate prognosis and to discuss appropriate treatment options.

Can lymphoma be treated?

The simple answer is yes. It is very uncommon for lymphoma to be cured, but treatment can make your dog feel well again for a period of time, with minimal side effects. This is called disease remission, when the lymphoma is not completely eliminated but is not present at detectable levels.

Without treatment, survival times for dogs with lymphoma are variable, depending on the tumour type and extent of the disease, but for the most common type of lymphoma the average survival time without treatment is 4 to 6 weeks. With current chemotherapy regimes such as the so-called Madison Wisconsin protocol, the average survival time is approximately 12 months.

Treatment options will be discussed in detail on an individual patient basis. Options include:

Steroid treatment (Prednisolone):

By itself, this increases average survival times to 1 to 3 months, but it does not work in all cases. It will also make subsequent treatment with chemotherapy less successful.

Chemotherapy:

using medications to stop or hinder cancer cells in the process of growth and division.

What does chemotherapy involve?

On each treatment day, before receiving chemotherapy, your pet’s progress is discussed, together with us performing a full physical examination and blood tests. Following this assessment, chemotherapy doses are calculated and the drugs are administered either subcutaneously (under the skin), intravenously (into a vein) via a catheter, or orally.

Chemotherapy with the Madison Wisconsin protocol involves your pet having chemotherapy treatments weekly for nine weeks (with a one week break), then fortnightly up until 6 months (i.e. 25 weeks in total). At 6 months, if your dog is in remission, therapy will be discontinued. Chemotherapy can be restarted when a patient relapses i.e. when lymphoma comes back. Patients are individuals, so the response varies from case to case, and because of this, all patients receiving chemotherapy are carefully monitored and protocols adjusted to suit the individual.

What are the potential side effects of chemotherapy and how can they be minimised?

Side effects can be seen because chemotherapy agents damage both cancer and normal rapidly dividing cells. Normal tissues that are typically affected include the cells of the intestine, bone marrow (which makes the red blood cells, white blood cells and cell fragments involved in blood clotting called platelets) and hair follicles. Hair loss is uncommon in dogs having chemotherapy, but it can be seen in certain breeds that have a continuously growing coat, such as Poodles and Old English Sheepdogs (cats rarely develop hair loss, but may lose their whiskers). Hair usually grows back once chemotherapy is discontinued. Damage to the cells of the intestines can result in changes in appetite or stool consistency and occasionally vomiting. Damage to the bone marrow reduces blood cell production, particularly infection fighting white blood cells (neutrophils).

Steroids are often used in combination with chemotherapy. These medications can make patients feel that they want to eat and drink more (especially during the first week of therapy when doses are usually higher and given every day). Patients should not have their access to drinking water restricted, but it is important not to increase their food intake, as excess weight gain can be problematic. The increased thirst is associated with increased urination, so patients may also need to go out to pass urine more often.

Cyclophosphamide, one of the commonly used chemotherapy agents, can cause irritation to the lining of the bladder, producing cystitis-like signs, so it’s important to bring urine samples when requested and to monitor your pet’s urination very carefully, and to promptly report any signs of problems.

Epirubicin, another chemotherapy agent, can cause damage to the heart muscle over time. The more doses your dog has, the greater the risk. For this reason, we will carry out checks on the heart before the drug is given for the first time and at various points during the treatment course. Heart complications are extremely uncommon and your dog is at much greater risk if the lymphoma is not treated.

We prescribe medications to help to prevent complications, and we will advise you on which signs to monitor. Compared to human patients who receive chemotherapy, pets experience fewer and less severe side effects, and these can usually be managed at home. This is because we use lower drug doses and do not combine as many drugs as in human medicine. Your pet’s quality of life is really important to us and to you.

What precautions do I need to take at home, with my pet having chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy agents can be excreted in the urine and faeces, and care must be taken when handling your pet’s waste. You will be advised of appropriate precautions, and it is important to note explicitly that pregnant women should avoid contact with the pet’s waste following chemotherapy.

What should I look out for?

Signs of gastrointestinal upset: if your pet has vomiting or diarrhoea for more than 24 hours please contact us or your usual vet. Also watch for any dark coloured faeces.

Signs of bone marrow suppression: Neutrophils (infection fighting white blood cells) are at their lowest point usually 5 to 7 days after treatment. If your pet is depressed, off its food, panting excessively or is hot to the touch at this time, please contact us.

Signs of bladder problems: you should alert us if your dog is urinating more frequently than he or she has been, is straining or having difficulty passing urine, or if you see blood in the urine.

What will happen in the future?

Unfortunately, chemotherapy for lymphoma is very unlikely to cure your pet, but will allow a good quality of life to be enjoyed for some time.

Inevitably, the cancer cells become resistant to the drugs we use, and the cancer will come back. At this stage, it is often possible to get the cancer back under control for a while with alternative agents (this is known as a ‘rescue’ treatment). Eventually, the tumour cells will become resistant again and it is likely that your pet will have to be put to sleep when his or her quality of life deteriorates.

Hopefully, this will be after many happy months of good quality life for your pet and you to enjoy together.

Canine Mast Cell Tumours

by admin on October 4th, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Mast cells are normal cells found in most organs and tissues of the body, and are present in highest numbers in locations that interface with the outside world, such as the skin, the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract (stomach and bowels). They contain granules of a chemical called histamine which is important in the normal response of inflammation. When mast cells undergo malignant transformation (become cancerous), mast cell tumours (MCTs) are formed. Mast cell tumours range from being relatively benign and readily cured by surgery, through to showing aggressive and much more serious spread through the body. Ongoing improvements in the understanding of this common disease will hopefully result in better outcomes in dogs with MCTs.

Why do dogs get Mast Cell Tumours (MCTs)?

This is unknown, but as with most cancers is probably due to a number of factors. Some breeds of dog are predisposed to the condition, and this probably suggests an underlying genetic component. Up to 50% of dogs also have a genetic mutation in a protein (a so-called receptor tyrosine kinase protein) which inappropriately drives the progression of mast cell cancer cells.

The role of these receptor tyrosine kinases in canine MCTs is very interesting and also important in understanding the role and mechanisms of the newer drugs available for treating canine MCTs: the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (see Treatment Options).

Where in the body do MCTs occur?

The vast majority of canine MCTs occur in the skin (cutaneous) or just underneath the skin (subcutaneous). In addition, they are occasionally reported in other sites, including the conjunctiva (which lines the eyeball and eyelids), the salivary glands, the lining of the mouth and throat, the gastrointestinal tract, the urethra (the tube from the bladder), the eye socket and the spine.

Breed predisposition

Some breeds of dog are predisposed to getting mast cell tumours, amongst them are:

- Australian Cattle Dog

- Beagle

- Boston Terrier

- Boxer

- Bull Terrier

- Bullmastiff

- Cocker Spaniel

- Dachshund

- English Bulldog

- Fox Terrier

- Golden Retriever

- Labrador Retriever

- Pug

- Rhodesian Ridgeback

- Schnauzer

- Shar-Pei

- Staffordshire Terrier

- Weimaraner

- before surgery to shrink a tumour down

- after surgery if the tumour appears more aggressive on analysis of a biopsy

- as palliative treatment if a tumour cannot be removed, has already spread or if an owner does not want to pursue surgical intervention.

- Rales (clicking, rattling, or crackling noises)

- Coughing

- Nasal discharge

- Discharge from around the eyes

- Swelling under the eyes

Some breeds tend to get MCTs more commonly in certain locations, but more importantly MCTs sometimes behave in a certain way in certain breeds. For example, Pugs are renowned for getting large numbers of low-grade (less aggressive) tumours, and Golden Retrievers commonly get multiple tumours. Boxers with MCTs are generally younger than other breeds, and more commonly have lower-grade MCTs with a more favourable prognosis. In contrast, Shar-Pei’s usually get aggressive high-grade and metastatic (spread to other sites) tumours, often at quite a young age. MCTs in Labrador Retrievers are also frequently more aggressive than in other breeds.

Age

The average age of dogs at presentation is between 7.5 and 9 years, although MCTs can occur at any age.

Paraneoplastic syndromes and complications of granule release

Cancerous mast cells contain 25 to 50 times more histamine than normal mast cells. Histamine is a very inflammatory chemical, and therefore explains why some MCTs wax and wane or suddenly increase in size due to inflammation – especially after they have undergone biopsy/needle aspiration (see diagnosis). Histamine also causes the stomach lining to produce more acid – this can result in stomach ulcers, causing signs such as vomiting or black, tarry stools (this appearance is due to the presence of digested blood coming from the ulcer).

The outlook (prognosis) –

Can we predict whether a dog will do well or not do well due to their MCT? No single factor accurately predicts the biological behaviour or response to treatment in dogs affected by MCTs. Various clinical factors can influence the outcome, such as whether it has spread, potentially the breed and also the tumour location. Tumours in the nail bed, inside the mouth, on the muzzle, in the groin area and in those sites where the skin meets mucus membranes (mucocutaneous junctions), are often correlated with a worse prognosis than those in other parts of the body, although this is not always the case.The single most valuable factor in predicting the outcome for most patients is the grade of the tumour when assessed under a microscope (the histological grade).

How is MCT diagnosed?

Cytology – This means looking at the cells under a microscope, and the sample for this is usually obtained by ‘fine-needle aspirate’. Fine-needle aspirates of MCTs involve taking a small sample of the tumour with a thin needle. This is generally a straightforward procedure which can be done conscious and without sedation in most patients. It should be performed prior to any surgery, because a pre-operative diagnosis of MCT influences the type and extent of surgical intervention required.

Biopsy - This involves taking a larger piece of tumour tissue and sending it away to a pathologist for analysis. This can be performed to help decide on the best treatment, or it can be performed when the tumour has been removed to find out the grade of the tumour.The pathologist looks at the sample of the tumour under the microscope and performs grading to indicate how aggressive the tumour is.

MCT grade and outlook (prognosis)

Low grade (grade 1) tumours and around 75% of intermediate (grade 2) tumours are cured with complete surgical excision. Unfortunately, most high grade (grade 3) tumours and around 25% of intermediate grade tumours have already spread by the time they are diagnosed (even if this spread cannot be detected on scans at the time of diagnosis). These cases benefit from chemotherapy treatment. In some dogs, further analysis of the biopsy samples is useful in determining the best management options. The tumour grade is very important in determining the appropriate therapy for dogs with MCTs.

Further investigations – ‘staging’ of the MCT

As well as performing fine needle aspiration and biopsies of the MCT to determine its grade, additional tests may be required to determine the stage of the tumour i.e. whether or not it has already spread. These further tests can include sampling of nearby lymph nodes, chest X-rays and abdominal ultrasound scanning. Which tests are performed will depend on a number if factors, and these will be discussed with you by the specialist.

Treatment options

Surgery is the cornerstone of management of MCTs, and complete surgical removal is often curative in dogs with low or intermediate grade MCTs. However, to achieve a cure, in some circumstances a significant amount of tissue surrounding the tumour must be excised to ensure that all the tumour cells are removed. This can require a high level of surgical experience and expertise, in order to perform complex reconstructive surgical techniques and may require referral to a specialist.

If complete removal is not possible, or where the tumour appears to be more aggressive (e.g. high-grade) then radiation therapy and chemotherapy treatments become more useful. The optimum treatment depends on the tumour grade, stage and other factors unique to the individual dog.

Chemotherapy can be used:

Fortunately, the drugs used for chemotherapy in MCTs are extremely well tolerated and most owners are very happy with their dog’s quality of life on treatment. A new group of drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors is also available – these block proteins (called tyrosine kinases) which are found on the surface of cancerous mast cells. They can be used where tumours cannot be surgically removed or have recurred despite previous treatments. They can have some side effects, but most dogs tolerate these drugs well.

In some instances referral may be recommended to an RCVS Recognised Specialist in the fields of both medical and surgical oncology. The expertise provided by a combination of medical and surgical cancer specialists has particular advantages in MCT treatment.

Summary

Dogs have a unique risk to develop MCTs in the skin, and they can be frustrating to manage, even for specialist oncologists.

Knowing what the best treatment is for an individual dog depends on knowing the grade of the MCT and whether or not it has already spread.

It is important to recognise that most dogs can survive for a long time with mast cell cancer and can be cured. However, some dogs have a more aggressive type of MCT and treatment in these cases is of a more palliative nature, trying to improve patient comfort and life expectancy, but without being able to achieve a cure.

If you have any queries or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Glaucoma

by admin on August 31st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What is glaucoma?

Glaucoma is an increased pressure inside the eye, caused by an obstruction to the drainage of the fluid from within the eye. In order to keep the eye inflated, fluid is normally produced and cleared away from the eye all the time. The fluid inside the eye is not related to the tear fluid (which is on the surface of the eye).

The blockage of fluid drainage within the eye can be due to an inborn defect (primary glaucoma) or due to another eye disease that interferes with drainage of the fluid inside the eye (secondary glaucoma). Common causes of secondary glaucoma are inflammation inside the eye or a shift of the position of the lens within the eye.

Is my dog at risk?

Many cases of primary glaucoma are inherited and due to an abnormally formed drainage passage within the eye. Affected breeds include the Basset Hound, Welsh Springer Spaniel, Cocker Spaniel, Siberian Husky, Great Dane, the Flat Coated Retriever and many others. Often one eye is affected initially but there is a high risk that the other eye will follow at some point in the future.

A test (gonioscopy) is available to determine the predisposition of your dog to develop glaucoma. In this test, a special contact lens is applied to the eye to allow assessment of the structure concerned with drainage of fluid from the inside of the eye.

What are the signs of glaucoma?

In most cases, the disease develops very rapidly. The patient is often depressed and reluctant to exercise. The eye becomes blind and appears red, painful and sore with a bluish tinge over the cornea. Less commonly, the pressure increase is slow and the clinical signs are not as pronounced. However, a gradual reduction in vision is often noticed.

How is glaucoma diagnosed?

A special instrument called a tonometer is used to measure the pressure inside the eye. Local anesthetic is applied to the eye for this test which is usually very well tolerated.

Is treatment possible?

The aim of treatment in glaucoma is to preserve vision and to relieve the pain caused by the pressure increase. In order to reduce the pressure within the eye, drugs are given to reduce fluid production within the eye and to improve removal of fluid from the eye. In some cases of secondary glaucoma (see previously mentioned), treatment of the underlying cause, such as anti-inflammatory medication or removal of a dislocated lens, can lead to the pressure decreasing.

Patients with primary glaucoma are more difficult to treat and it is important to realise that no cure for the disease exists. In some patients, pressure control can be achieved with medical treatment only. However, with time, most patients become less responsive to the treatment and surgical alternatives may have to be considered. These include laser therapy or the surgical placement of a drainage implant into the affected eye.

Regular check ups will also be necessary to re-assess the second eye and check its pressure.

Is preventative treatment available for the second eye?

No preventative treatment is available that can totally stop glaucoma developing in the second eye. However, there is evidence that with the help of medication, the onset of the condition in the second eye may be delayed.

What happens if the pressure cannot be controlled?

Eyes that have lost vision but continue to have an increased pressure are a cause of chronic pain for the patient. Removal of the eye must be considered in such cases to ensure the welfare and comfort of the patient. Occasionally, both eyes may, unfortunately, be lost. Should this be the case, most dogs will adapt very well to being blind and continue to lead a good quality life.

Syringomyelia

by admin on August 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Syringomyelia is a relatively common condition, especially in breeds like the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and the Griffon Bruxellois, in which it is suspected to be an inherited disorder. Other names that have been used to describe this condition include syringohydromyelia, Arnold-Chiari or Chiari-like malformation, and caudal occipital malformation.

What is syringomyelia and what causes it?

Syringomyelia is a neurological condition where fluid filled cavities develop within the spinal cord (the bundle of nerves that run inside the spine). The most common reason for the fluid build-up is that there is an abnormality where the skull joins onto the vertebrae (the bones of the spine) in the neck, causing fluid in the brain (called cerebrospinal fluid or CSF) to be forced down the centre of the spinal cord, where it causes the tissues to become distended and cavities to form.

What are the most common signs of syringomyelia?

Clinical signs or symptoms can vary widely between dogs and there is no relation between the size of the syringomyelia (cavity in the spinal cord) and the severity of the signs – in other words a dog with severe fluid build-up can have relatively mild symptoms, and vice versa. The most common symptom that develops is intermittent neck pain, although back pain is also possible. Affected dogs may yelp and are often reluctant to jump and climb. They may feel sensations like ‘pins and needles’ (referred to as hyperaesthesia). Another common sign is scratching of the neck and shoulder region called ‘phantom scratching’, as there is generally no contact of the foot with the skin of the neck. Occasionally dogs become weak or wobbly if there is significant damage to nerves within the spinal cord. Cavalier King Charles Spaniels will typically show clinical signs between 6 months and 3 years of age. Not all dogs with syringomyelia will show signs of pain or other clinical symptoms, so the presence of syringomyelia can be an incidental finding on an MRI scan or specialised X-rays, when neurological investigations are being performed.

Other neurological conditions, such as slipped discs (cervical and thoracolumbar disc disease), can mimic the signs of syringomyelia and it is important for us to rule them out before concluding that your pet is suffering from syringomyelia.

How can syringomyelia be diagnosed?

The best method of diagnosing syringomyelia is an MRI scan of the brain and spine. It is necessary to perform this investigation under a general anaesthetic. The scan and anaesthetic are safe procedures. In the future it is possible there will be a genetic test to identify dogs with syringomyelia.

How can syringomyelia be treated?

Medical therapy is usually the treatment of choice in dogs suffering from syringomyelia. Several types of medication are used to manage episodes of pain, including a drug called gabapentin. This drug is safe, with few side effects apart from possible sleepiness. Other medications that may be used include anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids and drugs that reduce the production of fluid in the brain and spinal cord.

Occasionally medical management is unsuccessful and surgery needs to be considered. The aim of surgery is to improve the shape of the back of the skull and reduce the flow of fluid down the centre of the spinal cord. Many dogs will improve following surgery, although some patients will have persistent signs despite surgery, whereas others may show improvement initially but then develop recurrence of their symptoms.

Disc Disease in Dogs

by admin on July 4th, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Dachshunds and similar breeds such Pekingese, Lhasa Apsos and Shih Tzus, have short legs and a relatively long back. These breeds suffer from a condition called ‘chondrodystropic dwarfism’. As a result they can be prone to back problems, more specifically disc disease.

What are intervertebral discs?

The intervertebral disc is a structure that sits between the bones in the back (the vertebra) and acts as a shock absorber. The structure of a disc is a little like a jam doughnut with a tough fibrous outer layer (annulus fibrosus) like the dough, and a liquid/jelly inner layer (nucleus pulposus) like the jam.

In chondrodystrophoid breeds like dachshunds, the discs undergo change where the nucleus pulposus changes from a jelly-like substance into cartilage. Sometimes the cartilage can mineralise and become more like bone and show up on an x-ray. In these breeds, this change occurs in all discs from approximately one year of age and is considered part of usual development for these dogs. This change in the discs is a degenerative process and predisposes the disc to disease.

The most common type of disc disease in dachshunds and other chondrodystrophoid breeds is ‘extrusion’. This is where the annulus fibrosus ruptures and allows the leakage of the nucleus pulposus into the spinal canal. An analogy we often use is the jam leaking from a jam doughnut when it is squeezed.

What are the signs of disc disease in dachshunds and other breeds?

The first evidence that there might be a problem is that your dog may be in pain. This may consist of yelping and/or a hunched back and more subtle signs such as quietness and inappetence (lack of appetite). Back pain is commonly mistaken for abdominal pain.

After pain there may be mobility problems. The first thing to occur is wobbliness of the hind limbs – termed ‘ataxia’. After this, weakness can develop with the wobbliness, which is termed paresis. Subsequently, the patient may lose control of the back legs altogether and not be able to walk. If there is no movement in the hind limbs this is ‘paralysis’.

Will my dog need to be referred to a specialist?

Spinal disease can sometimes be difficult to manage and your dog may be referred to a specialist. At the referral clinic, your dog will be assessed by the specialist neurologist or neurosurgeon. They will test various reflexes to decide where they think the issue may be. They will perform a clinical examination which will assess for other disease processes and look for any areas of pain. One thing that is important to assess is the presence of pain sensation. We call this ‘deep pain sensation’. To assess this, the specialist will pinch your dog’s toes, usually with fingers initially but it may need to be with forceps. This is not a pleasant test to perform but it is necessary as the presence of deep pain comes with a more favourable prognosis. The loss of deep pain sensation means the prognosis is worse and without surgery is considered very poor.

What investigations will be performed?

After the clinical examination, we will generally have a good idea where the problem is and the next step is to confirm the diagnosis. The best way of diagnosing disc disease is with MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CT (computed tomography). With MRI we get detailed information about the soft tissue such as the disc itself and the spinal cord. Computed tomography uses the same technology as x-ray and provides good information about the bone and mineral structures and can tell us where the lesion is and whether or not surgery is indicated.

How is disc extrusion treated?

If a disc extrusion – the ‘jam out of the doughnut’ scenario – is diagnosed then we can opt for conservative care or surgical management.

Conservative care is a non-surgical management and can be considered in dogs where the signs are mild or intermittent and when there is only mild compression of the spinal cord. It can also be considered if there are concerns regarding the cost of surgery.

Surgical treatment involves making a window through the bone structures of the vertebra, into the spinal canal, a procedure called a ‘hemilaminectomy’. Once into the spinal canal, the disc material (nucleus pulposus) is removed and the spinal cord is decompressed. Surgical treatment tends to give a speedier and more predictable recovery and is often considered the treatment of choice, where indicated.

What is the prognosis for a dog with disc disease?

When dealing with spinal injury, particularly from disc disease, we aim for patients to achieve a functional recovery. This means the patient is pain free, is able to get around on their own (although they may still be wobbly) and able to toilet themselves unaided. Whether a patient will return to normal or whether there will be residual deficits is down to the individual.

The prognosis for patients who have intact deep pain sensation is favourable, with most patients (80-90%) achieving a functional recovery. In patients without deep pain sensation, the prognosis is guarded, with only 50% of cases achieving a functional recovery but without surgery the prognosis for a functional recovery is approximately 5%.

Surgery tends to speed recovery and aid early pain control. We expect most patients to recover within the first 2 weeks after surgery, with a smaller number of patients taking longer (2-6 weeks). If there is no improvement after 6 weeks the prognosis becomes more uncertain and long term disability may be present. This occurs in approximately 1 in 10 patients.

Mycoplasma in Poultry

by admin on May 30th, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

The ‘Head Cold’ of the Poultry World

As more and more pet owners are keeping poultry we felt it appropriate to look at one of the most common infections that may be seen.

The main culprit of Mycoplasma infection in backyard poultry is Mycoplasma gallisepticum. This is one of the organisms that makes up the colloquially-termed ‘chronic respiratory disease syndrome’ (potentially in association with Infectious Laryngotracheitis) in poultry worldwide. It is considered to be responsible for some of the greatest economic losses throughout commercial flocks around the globe, but can just as easily impact on smaller backyard flocks.

Who catches Mycoplasma, and how?

Poultry, including chickens and turkeys, are most often presented with respiratory issues involving Mycoplasma gallisepticum, but a wide range of other birds including pheasants and wildfowl can be affected.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum can be spread vertically (from hen to egg) leading to infected chicks, or, and perhaps more commonly, through horizontal transmission (bird to bird). The disease can be spread short distances through the air as an aerosol, or on shoes/water drinkers/feeders. The disease itself may remain dormant within the infected bird for potentially months before causing any overt clinical disease. It is often at this stage that rapid spread of the disease occurs throughout a flock.

What does Mycoplasma in poultry look like?

Focusing on the presenting signs of poultry, the degree of clinical signs can vary widely from no apparent signs up to the potential death of the bird in more aggressive, complicated disease development.

The more common presenting signs can include:

In more advanced cases, sinusitis may become apparent.

There may also be more generic signs of illness present including the birds appearing fluffed up, off food, keeping themselves away from the rest of the flock and reduction in egg production or going off lay completely.

Clinical signs are often quicker to develop and more severe in turkeys than chickens.

Can Mycoplasma in poultry be treated?

Mild to moderate disease can be treated successfully with appropriate antibiotics prescribed by your vet, pain relief and good nursing management (TLC!). It is important to note however that once your bird/flock has suffered from the disease, it likely to circulate and be present from thereon in. This becomes an important factor when either bringing in new birds or selling/moving your own birds.

Chickens, as well as most other birds, will suffer a much more marked immune ‘crash’ when stressed in comparison to other animals. This means that when birds are moved to a new location or mixed with other birds, the stress can induce a marked reduction in their active immunity causing a rapid onset of disease symptoms (sneezing, coughing, etc.).

Due to the risk of disease spread amongst new birds, it is absolutely vital to quarantine any incoming birds for at least 3-4 weeks to ensure that you are not putting your own birds at risk of disease.

Prevention is better than cure!

Vaccinations are available against certain strains, but use of a vaccine must be with caution as quarantine procedures would still always be advised, and any new birds bought in would have to have been vaccinated. The danger with vaccinating poultry is that all too often it is seen as an easily-achievable blanket cover for disease. Good biosecurity, involving washing boots, is important. Always thoroughly disinfect items that are brought in or taken off the holding containing your particular birds.