News

Archive for the ‘News’ Category

Canine Demodicosis

by admin on January 2nd, 2019

Category: News, Tags:

What are Demodex mites? And what is demodicosis?

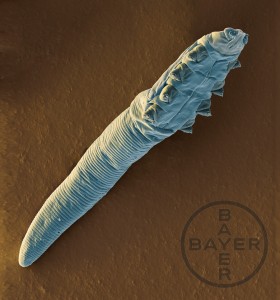

Demodex spp. are cigar shaped microscopic parasitic mites that live within the hair follicles of all dogs. These mites are passed to puppies from their mothers in the first few days of life, and then live within the hair follicles for the duration of animal’s life without causing problems. It is thought that the body’s immune system helps to keep mite numbers ‘in check’ and prevent the populations getting out of control. For the vast majority of dogs, these mites never cause a problem. However in some instances, mite populations become huge resulting in inflammation and clinical disease. This disease is called demodicosis.

What causes demodicosis?

There are two presentations of demodicosis depending on the age at which it develops. Juvenile onset demodicosis tends to occur in puppyhood between the ages of 3 months and 18 months, and occurs in both localised and generalised forms. The exact cause is quite poorly understood but probably occurs due to a mite specific genetic defect in the immune system which allows mite numbers to increase. This defect may or may not resolve as the puppy ages. It is thought to be ‘mite specific’ because these puppies are healthy in all other respects and do not succumb to other infections. Generalised demodicosis can be a very severe disease. Adult onset demodicosis usually occurs in the generalised form and in dogs over 4 years of age. It is generally considered a more severe disease than its juvenile onset counterpart. In these cases, mite numbers have been controlled in normal numbers in the hair follicles for years prior to the onset of disease, which tends to result from a systemic illness affecting the immune system. Common triggers for adult onset demodicosis include hormonal diseases and cancer.

What are the clinical signs?

Localised demodicosis in juvenile dogs presents as patches of hair loss and red inflamed skin. These patches often occur around the face, head and feet and are not typically itchy.

Generalised disease in juvenile and adult dogs is a more serious disease, although there is no uniformly accepted way of defining the number of lesions needed to classify generalised disease. Patches of hair loss and inflammation develop which often coalesce into large areas of thickened skin and sores. As the parasites damage the hair follicles, secondary bacterial infections are very common and affected dogs can develop discharging lumps within the skin. Bleeding from these lesions is not uncommon. As with the localised form, lesions often start around the head, face and feet, but often spread to involve large areas of the body surface. The ears can also be affected with this parasite, resulting in secondary infections. Itchiness and pain are commonly seen.

How is it diagnosed?

Demodicosis can often be suspected following a review of the animal’s history and assessment of the clinical signs. The parasitic mites within the hair follicles result in plugging and the formation of ‘black heads’. The plugged follicles also cause large amounts of scale to be present on the hairs themselves. Demodicosis can usually be diagnosed relatively easily. Hairs can be plucked from the affected skin and then examined under a microscope for the presence of the mites. Alternatively, the skin can be squeezed and then scraped with a blade to collect up the surface debris from the skin. This material is then also examined under a microscope for the parasites.

If the numbers of mites are abnormal and if mites can be recovered from multiple sites, demodicosis can be diagnosed. Rarely, a biopsy of affected skin is needed to diagnose the condition.

Is it contagious?

Demodex mites from dogs are considered non-infectious to in-contact animals and people. It is thought that Demodex mites can only be passed between dogs in the first few days of life from the mother to the pup.

How is it treated?

The treatment used for demodicosis depends on the age of the animal and the severity of the disease. Mild and localised forms of demodicosis in young dogs may not require treatment, and may resolve spontaneously as the animal ages. These cases should be closely monitored if no treatment is given. Generalised cases in young dogs and those in adult dogs require intensive treatment. Secondary infections must be treated with courses of antibiotics, and a swab is often submitted to a laboratory to grow the organisms to ensure the correct antibiotic is selected. The licensed treatments for demodicosis in the UK include a dip solution called Aludex and a spot-on product called Advocate. The dip is performed on a weekly basis until mite numbers are brought under control. Advocate spot-on is generally used for milder cases and is usually used monthly. In severe cases not responding to the licensed treatments, off-licence treatments must be used. Some of these drugs, such as Ivermectin and Milbemycin, are used for demodicosis in other countries.

An essential part of treating adult onset cases is to identify the underlying illness that triggered the problem. This often requires blood testing and scans (CT, ultrasound) to investigate.

Treatment must continue until mite numbers have returned to a normal level and this can take a very long time. This can only be assessed by repeat sampling of the patient using plucks of the hair or scrapes of the skin

What is the prognosis?

The prognosis for localised disease in young dogs is very good, and most recover uneventfully from the disease. Generalised cases in young dogs can take many weeks or even months of treatment, but it is usually possible to control the disease with a good long term outlook.

The prognosis for adult onset generalised demodicosis is far more uncertain, as many of these dogs have an underlying systemic illness. If this illness can be identified and cured, the prognosis for managing the demodicosis is much better. Some cases require long term medication to keep mite numbers controlled.

Patellar Luxation

by admin on December 3rd, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

What is patellar luxation?

The patella is a small bone at the front of the knee (stifle joint). In people it is referred to as the ‘knee-cap’. It is positioned between the quadriceps muscle and a tendon that attaches to the shin bone (tibia). This is termed the quadriceps mechanism. The patella glides in a groove at the end of the thigh bone (femur) as the knee flexes and extends.

Occasionally the patella slips out of the groove. This is called luxation, or dislocation, of the patella. Most commonly the luxation is towards the inside (medial aspect) of the knee, however, it can also dislocate towards the outside (lateral aspect) of the joint.

Patellar luxation can affect dogs and cats.

Why does the patella luxate?

The patella luxates because it (and the quadriceps mechanism in general) is not aligned properly with the underlying groove (trochlea). The resultant abnormal tracking or movement of the patella causes it to slip out of the groove.

The cause of the abnormal alignment is often quite complex, involving varying degrees of deformity of the thigh bone (femur) and shin bone (tibia). In severe cases in dogs, the thigh bone (femur) is bowed at the end due to abnormal growth. These dogs often have either a bow-legged or knock-kneed appearance.

Patellar luxation is most common in certain breeds of dogs, such as Poodles, Yorkshire Terriers, Staffordshire Bull Terriers and Labrador Retrievers. Both knees (stifles) are often affected. These features suggest the condition may be genetic.

Luxation of the patella due to injury (trauma) is uncommon.

Is patellar luxation associated with any other knee (stifle) problems?

Patellar luxation is associated with the development of osteoarthritis within the knee (stifle). This occurs in every case. Osteoarthritis tends to be a progressive disorder and it is doubtful whether treatment of the patellar luxation reduces or stops this progression.

Occasionally luxation of the patella is associated with rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament in the knee (stifle). This may be due to chance or possibly due to abnormal forces on the joint that weaken the ligament.

What are the signs of patellar luxation?

The signs of patellar luxation can be quite variable. A ‘skipping’ action with the hind leg being carried for a few steps is typical. This occurs when the patella slips out of the groove and resolves when it goes back in again. If both patellae luxate at the same time, dogs and cats can have difficulty walking, often with a crouched action.

How is patellar luxation diagnosed?

Examination may reveal muscle wastage (atrophy), especially over the front of the thigh (the quadriceps muscles), although this is often minimal. Manipulation of the knee (stifle joint) may enable the detection of instability of the patella as it slips in and out of the groove. In some dogs the patella is permanently out of the groove. The severity of the luxation is graded from 1 to 4, with a grade 4 being the most severe.

X-rays (radiographs) provide additional information, especially regarding the presence and severity of osteoarthritis. Specific views may be necessary to assess the shape of the thigh bone (femur) and shin bone (tibia).

How can patellar luxation be treated?

Some dogs with patellar luxation can be managed satisfactorily without the need for surgery. The smaller the dog and the milder the grade of luxation (e.g. grade 1 out of 4), the more likely it is that this approach will be successful. Exercise may need to be restricted. Hydrotherapy is often beneficial. Dogs that are overweight benefit from being placed on a diet. Tit-bits may need to be withdrawn and food portions reduced in size. Regular monitoring of weight may be necessary.

Many dogs with patellar luxation benefit from surgery. The key types of surgery, which are described below, are: 1. quadriceps mechanism realignment, 2. trochlea deepening and 3. femoral osteotomy.

1. Quadriceps realignment surgery

The aim of this surgery is to move a small piece of bone (the tibial tuberosity) at the top of the shin (tibia) that is attached to the patella and reposition it so that the patella is correctly aligned with the groove in the thigh (femur) bone. This procedure is called a tibial tuberosity transposition. The transposed piece of bone is re-attached with one or two small pins, with or without additional support with a figure-of-8 wire.

Exercise following quadriceps realignment surgery must be very restricted for the first few weeks until the cut bone and soft tissues heal. It must be on a lead or harness to prevent strenuous activity, such as chasing a cat or squirrel. At other times, confinement to a pen or a small room in the house is necessary. Jumping and climbing should be avoided. After a few weeks, exercise may be gradually increased in a controlled manner (still on a lead). Hydrotherapy may be recommended.

2. Trochlea (groove) deepening surgery

In dogs and cats with patellar luxation the groove (trochlea) at the end of the thigh bone (femur) is often shallow. In these cases it may be necessary to deepen the groove. This can be done by removing a block or wedge of bone and cartilage from the groove, deepening the base, and replacing the block or wedge. These techniques are called ‘recession’ techniques since they recess the surface of the groove and thus make the groove deeper, while at the same time preserving the surface (cartilage) of the groove.

3. Femoral osteotomy surgery

Femoral osteotomy surgery involves changing the shape of the deformed thigh bone (the femur) by cutting it just above the knee (stifle) and stabilising it in a new position with a plate and screws. This may be all that is needed to prevent the patella luxating, however, in some dogs it is also necessary to perform a tibial tuberosity transposition.

Exercise following femoral osteotomy surgery must be restricted until the cut bone has healed. Exercise must be on a lead or harness to prevent strenuous activity. Jumping and climbing should be avoided. X-rays (radiographs) are necessary between six and eight weeks following surgery to ensure bone healing is progressing without complication. Exercise may then be gradually increased in a controlled manner. Hydrotherapy may be recommended.

What is the outlook with patellar luxation surgery?

The outlook or prognosis with patellar luxation surgery is generally good. Although all dogs and cats develop osteoarthritis to some degree, this is often not a cause of pain or lameness. Stiffness, especially after rest, can be a feature in some cases. Potential complications include recurrence of the patellar luxation and loosening of implants. These are uncommon.

Cataract Surgery

by admin on November 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

A cataract is an opacity or clouding in the lens in the eye. The opacity normally makes the lens look white. The lens in the eye is like the lens in a camera except that, rather than being at the front as it is in a camera, the lens in the eye is deep inside it, just behind the coloured part of the eye (the iris). The lens shows up as black in the central part of the eye (the pupil). The lens is normally crystal clear but it looks black because the darkness inside the eye shows through it. The lens is there to focus light on the sensitive tissue at the back of the eye (the retina).

Cataracts often form in both eyes and they frequently get worse. One eye is often more affected than the other, at least initially. It is not known why most cataracts develop. They are most common in older dogs and sometimes they occur due to other problems such as diabetes or disease in the back of the eye (the retina). Some cataracts are inherited.

What treatment is there for cataracts?

At the moment the only treatment for cataracts is surgery. Unfortunately not every cataract is suitable for surgical treatment, and it is necessary for the eye specialist to assess each patient and decide what therapy might be possible. Some cataracts are more complicated to treat than others, and the specialist will give guidance depending upon the circumstances in each case.

When is the best time to operate on a cataract?

The previous belief that it is best to let a cataract ‘ripen’ and the eye to become totally blind before removing the opaque lens (the cataract) has been proven wrong. Any cataract that is developing will cause potentially damaging inflammation in the eye due to release of lens proteins – a condition called ‘lens-induced uveitis’. Lens-induced uveitis can be subtle and easily missed – or, in some cases, it can be severe and associated with an obviously sore and inflamed eye.

Left untreated, even low levels of lens-induced uveitis are likely to result in complications, including adhesions (sticking) between the iris and the lens, retinal detachment (where the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye comes away from the back of the eye and stops working) and glaucoma (increased pressure in the eye which is potentially blinding and painful). Many eyes with long-standing cataracts that have not been operated on will eventually become irreparably blind and painful, and have to be removed as a result of the effects of lens-induced uveitis.

Early cataract surgery is therefore recommended in order to avoid the detrimental effects of lens-induced uveitis, and in general surgery is carried out once a cataract starts to interfere significantly with vision. This especially applies to young and diabetic patients, where progression of cataracts can often be rapid and result in significant complications if treatment is delayed. We will endeavour to see such patients at short notice and we will also often advise the referring veterinary surgeon to start treatment with topical anti-inflammatory drugs to manage lens-induced uveitis prior to us seeing the patient.

Cataracts in older dogs or patients with very slowly progressive cataracts may be monitored, but we will often recommend the prophylactic use of anti-inflammatory drugs in such cases.

The surgery

Your dog will usually be admitted on the morning of the surgery and no breakfast should be given. Water should not be withheld overnight. Diabetic patients need special management, and this should be discussed with the vet involved. After the patient is admitted, drops are given every 15 minutes prior to surgery to prepare the eye for the operation. These drops help to dilate the pupil and reduce the effects of inflammation which always happens in dogs having cataract surgery.

Before surgery all patients have an ultrasound scan to check for problems such as retinal detachment or rupture (bursting) of the lens. These changes are more common in advanced cases. The scan is performed under sedation. Some patients may be found to be unsuitable for surgery when the ultrasound scan is carried out.

Cataract surgery is performed under a full general anaesthetic and a muscle relaxant is given so that the eye comes into the correct position for the operation. This means that a ventilator needs to be used to inflate the chest during the procedure. We monitor your dog very carefully throughout the surgery using very modern sensitive equipment and the staff involved are specially trained in the procedure. This helps to reduce the risks of the anaesthetic to a very low level.

The operation is very delicate and involves the use of an operating microscope and tiny instruments. Two small cuts are made in the window of the eye (the cornea), near where the coloured part (the iris) joins the white part.

The lens is just behind the iris and lies in a delicate bag of tissue called the capsule. After the eye has been filled with a special gel called a viscoelastic, some of the lens capsule is taken out. The gel which is used helps to inflate the eye and protect the structures inside it from the effects of the surgery, and especially from the instruments and the ultrasound. The cataract (in other words, the lens) is then removed through the hole in the capsule using a technique called phacoemulsification – this is an ultrasound procedure using very sophisticated equipment which is exactly the same as that which would be used on a human eye. This type of surgery has been shown to give the best results in dogs’ and humans’ cataracts. There is currently no laser treatment for cataracts in dogs or humans.

In most patients it is possible to put in a special artificial lens where the old lens was. Plastic lenses make vision in the eye similar to the way it used to be before the cataract developed. The lenses used in our patients are made especially for dogs as they are bigger and more powerful than human lenses. They are permanent and buried deep inside the eye. The complication rate of lenses is very low indeed. For technical reasons it is not possible to implant an artificial lens in some eyes. Not having a lens implanted does not make the difference between being blind and having sight – it is similar to someone who wears glasses not putting them on.

At the end of the surgery the wounds in the eye are closed with tiny dissolving stitches. These are absorbed over the next few weeks, leaving only very small scars.

Some dogs can have both eyes operated on at the same time. The main reason for doing this is that it makes it more likely that the patient will have vision after the surgery – if something goes wrong with one eye, hopefully it will not also go wrong in the other one. However, a dog with one good eye will have overall vision which is almost as good as that in a dog with two good eyes, and so it is not essential to have both eyes operated on.

Most patients stay in overnight after their operation and are discharged the following day, provided that progress is satisfactory. Most dogs can see something on the day after surgery, but it frequently takes a few weeks for vision to settle down as the eye adjusts to the effect of surgery and the presence of a plastic lens implant. In addition, there is often some clouding inside the eye which takes time to clear.

Aftercare

The aftercare following cataract surgery is intensive. All patients develop inflammation inside their eyes after surgery. This happens more in dogs than in humans. Usually there are several types of drops used. The most frequently applied drops are used six times daily initially. The number of applications gradually decreases over the next two months or so. There are also tablets to be given for a few weeks after the surgery.

Your dog will need to be kept as quiet as possible for a few weeks after the surgery, although this can obviously be difficult with many of our patients! You can only do your best in this regard. Pulling on a lead should be avoided for several weeks after surgery, as this puts up the pressure inside the eye and can encourage bleeding. Avoiding pulling around the neck is best achieved by using a harness, and it is a good idea to obtain one before the operation – it can be fitted at the time that your dog goes home. A plastic Elizabethan collar also has to be worn for about a week after the operation.

There will need to be at least four or five re-examinations after surgery. These are mostly within the first two to three months after the operation. Some patients, especially those with complicated cataracts, may need longer term treatment and more check-ups than average.

Risks and complications

The success rate of cataract surgery in dogs is about 90 to 95% initially. This means that 5 to 10% of patients cannot see in the operated eye after surgery. There are various reasons why not all patients have a successful outcome or may have a less straightforward recovery than normal. These include:

Inflammation

Every patient gets inflammation after surgery, no matter how smoothly the surgery goes. This is usually well controlled by the medications which are given. The occasional dog gets more inflammation than average, and this can lead to changes in the eye. These may not be of any great significance, but sometimes they can cause reduced vision.

Occasionally an injection into the eye is needed to dissolve inflammatory clot material. Inflammation is the main problem in dogs after surgery, and is the major reason why frequent medications and regular post-operative check-ups are required.

Infection

This can be very serious, but is extremely rare. Antibiotics in the form of tablets and ointment are used before and after the surgery to help to prevent this.

Wound breakdown

This means that the wound gives way. Again this is an uncommon complication, but if it occurs another general anaesthetic will be required to re-stitch the wound.

Bleeding

A very small amount of bleeding at the time of surgery is not unusual and this is not a major problem. Very occasionally a larger haemorrhage can develop and this can affect vision.

Increased pressure

The pressure in the eye can occasionally go up in the first few days after surgery, but eye drops will usually settle this down very quickly. Rarely a more severe increase in pressure may develop (glaucoma). If this problem develops it will involve additional medication and possibly surgery. It can lead to blindness and even loss of the eye in severe cases which don’t respond to treatment.

Ulcers

Occasionally the surface layer of the window at the front of the eye (the cornea) can partly come away after surgery. This is usually a very minor problem which normally resolves within about a week.

Corneal oedema (water-logging)

The window at the front of the eye (the cornea) can very occasionally go blue after surgery due to disturbance of its inner layer. Careful surgery and the use of viscoelastic gel (as previously mentioned) help to reduce the chances of oedema developing.

Retinal detachment

This is an uncommon complication, but if the sensitive tissue at the back of the eye detaches it can lead to loss of sight. A routine ultrasound scan before the surgery helps to identify at-risk patients.

Poor vision

Some dogs have problems inside their eyes (for example with their retina) which cannot always be detected before the surgery, and this may then mean that the surgery is not successful, or that the vision given by the surgery is not as good as it once was. Some suspect cases may have an electrical test (an electroretinogram) performed on the eyes to look for retinal problems before surgery, but this may well require sedation or even general anaesthesia and is not necessary or recommended for every case.

‘After-cataract’

A small percentage of dogs that see well immediately after their surgery may not continue to do so for the rest of their lives. This later deterioration may happen for many reasons (such as some of the complications mentioned). However, one such problem is known as after-cataract, in which a white membrane can grow across the pupil inside the eye. In most patients the amount of after-cataract which forms is not significant, but it can very occasionally affect vision in the long-term. Having a plastic lens implant has been shown to help to prevent the membrane growing across the pupil.

If after-cataract becomes very severe it can be removed surgically, although this is very rarely necessary.

Conclusion

The success rate of cataract surgery in dogs is high, and the great majority of patients do very well after their operation. It is undoubtedly a major undertaking, but the procedure is one which is commonly performed.

Feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)

by admin on October 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

What are FeLV and FIV?

Feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) both belong to the same group of viruses, the retrovirus group. This means they are somewhat related to one another and act in a similar way. Retroviruses such as FeLV and FIV are particularly successful because the immune system usually fails to remove them completely (unlike many other viruses), so affected cats become infected for life. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is related to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but humans and cats cannot infect each other with their respective viruses.

How do cats get FeLV or FIV?

Cats can get FeLV and FIV through contact with other cats.

Feline leukaemia virus is usually transmitted through saliva, most commonly by friendly, social cats who like mutual grooming and do not mind sharing food bowls. However, FeLV can also be transmitted through bites.

Feline immunodeficiency virus is usually transmitted through biting by an infected cat, so individuals with FIV are typically entire tom cats or any other cats that like fighting.

What are the clinical signs of FeLV and FIV?

Both FeLV and FIV cause similar problems by gradually weakening the immune system. The protection this system normally gives against invading bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites functions less and less well, and infected cats become prone to infections that a healthy immune system would often just fight off. As the immune system also helps to protect the body against cancer, infected cats in advanced stages of the disease have a much higher chance of developing a cancerous disease. Anaemia is another common problem, particularly in cats with FeLV. Despite its name, feline leukaemia virus does not necessarily cause leukaemia – it can do so, but it also causes a multitude of other diseases.

When an infected cat becomes ill, the clinical signs seen are usually due to the secondary infection or the cancerous disease which develops, rather than the underlying FeLV or FIV infection. This means that there are no typical clinical signs for either disease. Vets usually become suspicious when cats are presented either with persisting infections which they should be able to fight off, or with ‘non-standard’ disease, or with several concurrent infectious problems, or if the response to treatment is not as expected.

How and when is the disease diagnosed?

There are two possible situations in which tests are carried out for either FeLV or FIV.

- FeLV or FIV is suspected as an underlying disease

- A healthy cat is tested for FeLV and FIV to ensure that he or she is not carrying the virus already. This may be advisable before a newly adopted cat is introduced into the household, before breeding is attempted or before the first FeLV vaccination is given.

Whatever the reason for testing a particular cat, it is usually possible to diagnose FeLV and FIV with a blood test that can be done at the surgery. However, in some cases we may suggest sending a blood sample to a laboratory for more advanced testing methods to be used.

Can FeLV or FIV be treated?

Cats carrying FeLV and FIV virus cannot be cured. Both viruses cannot be destroyed by medication – this is similar to the situation in people with HIV. In human medicine, advanced anti-viral drugs are now available – these can effectively suppress the activity of the virus for long periods of time. Few of these (very costly) drugs have been used in cats and it is not really known whether such drugs are effective for FeLV/FIV or safe for cats to take. This means that there is currently no recommended specific treatment against either FeLV or FIV.

As the majority of clinical signs caused by both FeLV and FIV are due to a non-functioning immune system, it is often possible to treat any secondary infections or problems, thereby giving the patient a reasonable quality of life for a longer period of time. However, it must be remembered that the infected individual is a danger to the rest of the cat population and will spread FeLV or FIV unless he or she is kept isolated from other cats.

Can FeLV or FIV be prevented?

Whilst FeLV cannot be treated once a cat carries the disease, it is possible to prevent infection by vaccination. FeLV vaccination is advisable for all cats that can go out or have contact with cats that go out. Only cats that are kept indoors and have no contact with other cats do not need FeLV vaccination.

Unfortunately there is no FIV vaccine which is licensed for use in the UK, so prevention is much more difficult than it is for FeLV. Any cat that is not kept indoors at all times is at risk of infection with FIV.

My cat has tested positive for FeLV or FIV – what is the outlook?

This can depend very much on why your cat has been tested. If he or she was tested because of severe or recurrent illness and is positive for one or both diseases, this means that the disease is already present and the immune system is already compromised. Under these circumstances unfortunately the outlook may be poor. It may be possible to give your cat a reasonable quality of life for a period of time with medication and very good care. However, he or she will be shedding the virus and will therefore be a danger to other cats. If other cats live in the family, they should certainly be tested – even if they appear healthy – in order to find out whether they are already carrying the virus.

If your FeLV or FIV positive cat is otherwise healthy and was tested as a routine precaution, then the outlook depends very much on the particular circumstances. Depending on the individual animal, it may take months or even many years before the disease breaks out and the cat will seem healthy in the meantime. However, he or she will be able to pass on the virus to other cats. This means that your cat should be kept indoors and away from other cats. It is also advisable to ensure good health through regular vaccinations and worming, very good nutrition and dental care.

While some cats are happy to stay indoors and away from other cats – especially if someone in the family is at home at all times, too – others will not like being so confined, especially if they are used to an outdoor life. Should such a situation arise, we will discuss the options with you in detail and should you feel that you are able to give your cat a good quality of life we will also discuss special health-care issues to keep your cat happy and comfortable for as long as possible.

Perineal Rupture

by admin on August 31st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

What is a perineal rupture?

A perineal rupture (sometimes called a perineal hernia) is a weakness or separation of the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm. The pelvic diaphragm is formed from a group of muscles that are situated around the rectum and form the caudal (back) wall of the abdominal cavity.

A perineal rupture is an abnormal hole in this diaphragm or sheet of muscles that allows fat or organs from the abdominal cavity to bulge into the area surrounding the anus (the perineum).

What are the clinical signs?

Clinical signs can include:

- Perineal swelling – this can fluctuate in size

- Perineal bruising

- Pain/discomfort associated with the swelling

- Pain or discomfort when passing of faeces

- Constipation

- Urine retention – an inability to empty the bladder properly

- Acute illness due to obstruction of urine flow from the bladder

- Generalised malaise

What animals are affected?

The condition predominantly affects middle aged to older male dogs, particularly entire (uncastrated) males. However, younger male dogs, female dogs and cats can also be affected.

What are the causes?

There is a strong association between perineal rupture and the male hormone levels in middle aged to older entire male dogs. Any disease process that affects the levels of male hormones can therefore predispose to perineal rupture.

In addition, any condition that results in straining or increased intra-abdominal pressure can result in failure of the pelvic diaphragm muscles.

Risk factors for perineal rupture include:

- Entire (uncastrated) male status

- Disease of the testicles (e.g. tumours)

- Disease of the prostate gland, which is found near the neck of the bladder in male animals (e.g. benign enlargement, abscess, cysts, tumours)

- Straining due to abdominal disease (e.g. colitis [inflammation of the large intestine])

- Pregnancy (due to increased abdominal pressure)

What does investigation involve?

In order to maximise the chance of successful treatment of the rupture, it is important to identify risk factors that are present in the patient and treat these at the same time as treating the rupture. Each investigation is likely to be tailored specifically to the patient, although typically this may include the following:

- Rectal examination (which may require sedation or general anaesthesia) – this will include assessment of the side opposite to the obvious rupture

- Blood tests

- Urine analysis

- Ultrasound scan of the abdomen and possibly of the hernia

- Prostate gland investigation/biopsy

- Examination of the testicles

- Chest X-rays in some cases

Cases with displacement of the bladder can present as emergencies and require urgent stabilisation prior to investigation and treatment.

What treatment options are available?

Most cases will require repair of the rupture and this is combined with castration in entire males to reduce the risk of failure. Those cases with other disease processes that have contributed to the development of the rupture will need to receive treatment for that underlying problem, prior to or at the same time as repair of the rupture.

Some ruptures are repaired using the muscles that are present within the pelvic diaphragm, although many require movement of additional muscle into the area in order to close the rupture. In some severe cases, mobilisation of a muscle from a hind leg or a synthetic mesh may be required to complete the closure.

Further support for the repair can be given by fixing the bladder and colon (large intestine) into the abdomen but this is not necessary in all cases.

What is the prognosis (outlook)?

Over 90% of uncomplicated cases receiving rupture repair and castration resolve following the surgery.

In experienced hands, complications following surgery are infrequent, and animals usually stay in the hospital for a few days to ensure they are comfortable and passing faeces easily.

Despite careful selection of the technique used and meticulous care, complications can occur in a minority of cases and these include:

- Recurrence of the rupture – stool softeners may be advised long term to reduce the straining during defaecation and therefore protect the repair

- Rupture of the other side

- Infection (the surgical site is in the perineal region, near to the anus which is a source of bacteria)

- Faecal incontinence – this is uncommon and usually temporary

Pododermatitis

by admin on August 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

What is pododermatitis?

Pododermatitis is a term used to describe inflammation affecting the skin of the feet. It often causes dogs to have swollen, red and itchy feet, which can progress to painful sores if left untreated. In very severe cases, dogs can even become lame. This is a relatively common skin problem in dogs and can be present on its own or as part of a more widespread skin problem. There are many causes of pododermatitis and in some patients more than one cause is present at the same time. It is important to obtain an accurate diagnosis so that the right treatment can be selected.

What causes pododermatitis?

Parasites

The parasitic mite Demodex can infect the haired skin of the feet and result in pododermatitis. Demodex mites are present in very low numbers in the skin of all dogs, but in some patients, either due to a genetic susceptibility, or due to a process that lowers the immune system, these mites can populate the skin in very large numbers causing disease. Pododermatitis due to these mites tends to result in hair loss, swelling and bleeding sores in some cases. This mite is not infectious to other animals or people, but requires specific treatment to reduce mite numbers down to normal levels again. Very rarely, other parasites can also contribute to pododermatitis.

Foreign bodies

Foreign bodies like grass seeds are a very common cause of pododermatitis in dogs. Foreign bodies tend to penetrate the skin of the feet when dogs are out walking/running and then trigger inflammation when they become trapped within the feet. The body often attempts to ‘expel’ these structures resulting in painful and often discharging lumps between the toes. Affected patients often lick and chew at the affected sites. Foreign bodies are particularly likely when one lesion is present on one foot.

Allergies

Allergic diseases in dogs and cats are very common, and results in inflammation in the skin. This inflammation is very commonly seen affecting the feet, and results in redness, excessive licking and chewing at the affected sites. The most common triggers for allergic pododermatitis are food items and environmental substances such as dust mites and pollens, and skin disease usually starts in early life between the ages of 6 months and 3 years.

Deep infections

A very common feature of pododermatitis, particularly in dogs, is a deep infection of the feet. This is usually due to bacteria, but can be due to rare fungal organisms, and often results in multiple painful, swollen and discharging lumps. Affected animals usually lick and chew excessively and can become lame in severe cases. Bleeding lesions are relatively common with deep infections.

Conformation

A frustrating cause of pododermatitis is termed conformational pododermatitis. This usually occurs in heavy set dogs with excessively splayed feet. This results in weight bearing on hairy parts of the foot adjacent to the footpads and triggers inflammation of the hair follicles. Over time, this inflammation damages the hair follicles and results in chronic inflammation with the feet. Dogs with this condition tend to have large areas of pad extension, with painful and swollen lumps around the toes.

Hormonal diseases

Certain hormonal diseases can also be involved in the development of pododermatitis as the local skin immune system is reduced and the ability to fend off infections is compromised. The most commonly involved diseases include an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) or overactive adrenal glands (Cushing’s disease). However, pododermatitis is a relatively rare symptom of these diseases and dogs and cats usually show other more characteristic symptoms.

How is pododermatitis diagnosed?

Diagnosis of pododermatitis can often be achieved following a thorough evaluation of the history and clinical signs. Hair plucks and skin scrapings are performed to diagnose Demodex mite infestation and swab samples are often taken to establish if an infection is present. If lumps are discharging fluid, a sample of this fluid may also be sent to a laboratory to grow (culture) any infectious organisms. If the clinical picture is very suggestive of a foreign body, X-rays may be needed along with a surgical procedure to remove the offending item. Allergies are often only diagnosed once infections/parasites are treated and removed. If redness and inflammation remain, allergy testing may be required. Hormonal diseases are often suspected if other clinical signs are present but usually require blood testing to diagnose. Conformational pododermatitis is usually diagnosed by examining the feet and assessing the shape (conformation) of the footpads.

What are the treatments available?

Treatments for pododermatitis vary depending on the underlying cause. Parasitic infestations are usually treated with dips/rinses for the feet. Deep infections are often treated with long courses of antibiotics or antifungal medications in the rare cases due to fungal infection. Foreign bodies are best treated by identifying the foreign body and removing it in a minor surgical procedure. Hormonal diseases require treatment specific to the condition, but sometimes involve supplementing with hormone, as is the case in hypothyroidism. Allergic diseases are treated by identifying the triggers and removing them if possible.

Conformational pododermatitis is perhaps the most difficult to treat, as the defect is due to the conformation of the patient. Many of these cases can only be managed rather than cured and require modifications such as protective boots, good foot hygiene and avoidance of rough and uneven terrain. In some of the very worst cases, conformational pododermatitis can be corrected with surgery to fuse the toe webs together.

What is the prognosis?

As there are numerous causes of pododermatitis and more than one can be present at the same time, a good prognosis depends on identifying all the contributing factors and correcting them if possible. If this can be done, the vast majority of cases will have a good outcome. Cases of conformational pododermatitis are rarely cured, and require long term management.

Recurrent Corneal Ulcers (Indolent Ulcers)

by Hannah Wright on July 9th, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

What is the cornea?

The cornea is the clear window of the eye. It is a delicate structure which is less than a millimetre thick. In order to be transparent, the cornea has no blood vessels. It consists of three layers which are arranged like those of a sandwich. The three layers comprise: 1) the epithelium – this is the thin outer ‘skin’ of the cornea; 2) the stroma which is the much thicker middle layer of the ‘sandwich’; 3) the endothelium – this is the inner layer of the cornea and is very thin indeed (only one cell thick).

What is a corneal ulcer?

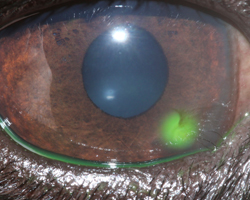

Any injury involving the cornea can be described as an ulcer. Generally, corneal ulcers are described as superficial or deep, depending on whether they just involve the outer skin (the epithelium), in which case they are called superficial ulcers or erosions – or whether they extend into the middle layer (the stroma), in which case they are called deep ulcers. The attached image shows the use of a dye called fluorescein which will stain ulcers and show up the defect. Most superficial ulcers heal rapidly as the cells of the surrounding outer ‘skin’ (the epithelium) slide and grow into the defect. The new skin that grows then sticks to the tissue underneath. Most superficial ulcers will have healed within a week.

How do I notice that my dog has an ulcer?

The cornea is sensitive because it has a lot of nerve endings, and ulceration is usually associated with quite marked discomfort because the nerves are exposed. Signs of eye discomfort include weeping, blinking, squinting, pawing at the eye and general depression.

What makes an ulcer indolent?

An indolent ulcer is an ulcer which fails to heal in the expected time. It then tends to cause ongoing discomfort and irritation. Eyes affected with indolent ulcers try to grow a new surface skin over the defect, but the incoming cells fail to stick down onto the layer underneath (the stroma). As a result, a thin layer of loose tissue can often be seen surrounding the ulcerated area. The reason why the cells fail to stick is not fully understood but is believed to be mainly because the epithelial cells fail to form tiny ‘feet’ that normally hold on to the tissue underneath.

Are certain breeds predisposed to develop indolent ulcers?

Certain breeds are predisposed to develop indolent ulcers – Boxers, Corgis, Staffordshire Bull Terriers and West Highland White Terriers are often affected. However, any dog can develop an indolent ulcer, and older patients are more commonly affected. Once a dog has suffered an indolent ulcer in one eye, it may develop one in the other eye, or recurrence of ulceration in the first eye. This can happen at any time after the first ulcer (sometimes years later).

What treatment options are available if my dog has an indolent ulcer?

It is not possible to achieve healing of indolent ulcers with the use of antibiotic or false tear ointments alone. In order for healing to occur, it is important that all loose tissue is removed and that the exposed stroma is treated and ‘freshened up’ to allow adhesion of new epithelial (‘skin’) cells. The process of removal of loose epithelium is called ‘debridement’ and in most patients it can be carried out with the use of local anaesthetic drops in the eye. Diamond Burr Debridement is the gold standard although other methods may be employed. Following the debridement, the exposed stroma is sometimes abraided with small dot-like scratches using a fine needle to allow the ‘feet’ of the new cells to take hold. The latter procedure is called a ‘punctate’ or ‘grid’ ‘keratotomy’.

In very fractious patients, it may be necessary to give a sedative to perform these procedures. More severe and longstanding cases require more radical treatment under a general anaesthetic. In this instance all diseased epithelium and some of the underlying stroma is removed. This procedure is carried out under the operating microscope with a sharp knife. The operation has a high success rate but is not suitable for every case.

What care will be required following debridement and cautery?

Usually, a broad spectrum antibiotic will be dispensed to be applied three times daily to help to prevent infection. In some cases, it may be necessary to give a drug (atropine) which widens the pupil and reduces pain associated with the ulcer. Often patients with an indolent ulcer will receive a painkiller which is given with food. In some patients, the pain associated with the ulcer appears more severe than in others.

How does the eye appear during healing of the ulcer?

In some patients, healing of the ulcer occurs fast and the cornea will only be slightly cloudy during treatment. However, in patients where healing of the ulcer is slow, it is common to find that blood vessels grow into the cornea and that pink granulation tissue forms to cover the defect. During this time, the eye may appear very red and odd looking. However, once the defect is fully covered, the granulation tissue will gradually clear over a period of months, leaving only minor corneal scarring in the majority of cases. Vision in most patients will return to normal or near normal after an episode of indolent ulceration.

How long does an indolent ulcer take to heal on average?

With a single treatment of debridement and cautery, approximately 80% of indolent ulcers heal within one to two weeks. The remaining 20% may require more than one treatment and, on occasions, it can take several weeks until full healing of an indolent ulcer is achieved.

The option of surgery for an indolent ulcer may have to be reconsidered if it fails to heal after several attempts at debridement and/or keratotomy.

What complications can occur if my pet has an indolent ulcer?

The biggest concern is certainly the possibility of infection. This can occur even if a suitable broad spectrum antibiotic is used on a preventative basis. If infection occurs, indolent ulcers may become deep and may require urgent surgical intervention.

Until healing of the indolent ulcer is achieved, it is advisable that the patient returns to the surgery to ensure satisfactory progress. Once the ulcer has fully healed, patients should not require frequent veterinary attention and a return will only be necessary in selected cases or if the problem recurs in either eye.

Healthcare advice for pets travelling abroad

by admin on June 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

When taking your pet abroad it is important to realise that there are potential disease risks which need to be considered. Animals from the UK will have no natural immunity to several diseases which are common in Europe and elsewhere.

The four main disease risks are Leishmaniasis, Babesiosis, Ehrlichiosis and Heartworm. All are potentially life-threatening and so must be carefully considered before travel. These diseases are all transmitted to pets when they are bitten by an infected insect (an insect which spreads a disease in this way is known as a vector). Different insects, or vectors, spread different diseases. With the exception of Heartworm, the only way to protect your pet from catching the disease is to prevent it being bitten by the vectors. Therefore, it is useful to know the feeding habits of the vectors and where they are likely to be found. The tables below give information about these diseases and their insect vectors.

The lists of geographical areas mentioned in the tables are not exhaustive. Also, high-risk times of day or year may be noted in the tables, but vectors will also feed outside these peak times. These diseases principally affect dogs, but cats may also be affected.

Whenever you are travelling abroad with your pet it is sensible to seek the advice of a local veterinary surgeon with regard to preventative health, as he or she will best know the local disease risks. If your pet falls ill while you are abroad you should seek veterinary assistance as soon as possible. It is worth finding out about local vets in the area before travelling, especially if the language is going to be a problem.

Should your pet fall ill after you have returned to the UK, do remember to mention to your veterinary surgeon that your dog or cat has travelled or lived abroad, even if it was years previously, as some of these diseases can take many years to emerge.

Leishmaniasis:

Cause of Leishmaniasis

- Protozoal Parasite

Vector

- Phlebotomine Sandfly

Where do Sandflies live?

- Woods and gardens (not beaches!)

- Mediterranean countries and islands

Feeding activity of Sandflies

- Potentially any time of day

- Peak activity May to October

Prevention of bites

- Do not allow dogs to sleep outside. Sandflies enjoy similar cool resting places to dogs!

- Allowing animals to sleep upstairs may reduce bites, as Sandflies have limited flight

- Environmental insect repellents – e.g. coils and plug-ins

- Scalibor repellent collar for dogs or Advantix

The speed of onset of illness

- It may take up to 6 years for signs to develop after an animal has been bitten

Clinical signs of illness

- Chronic or recurrent weight loss, skin and eye lesions, lameness and enlarged lymph nodes

Treatment

- Variable success of treatment

Special considerations

- Zoonosis (i.e. it can potentially be passed to humans)

Babesiosis:

Cause of Babesiosis

- Protozoal parasite of the red blood cell

Vector

- Tick

Where do Ticks live?

- Forest and rough grazing including campsites!

- France, Southern Europe but as far north as Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands

Feeding activity of Tick

- Especially Spring and Autumn

Prevention of Tick bites

- Prevent tick attachment – repellent collars (Scalibor for dogs)

- Treatments to kill attached ticks – Frontline (cats) or Advantix (dogs)

- Daily checking and removal of ticks using Tick Hook (see note below)

Speed of onset of illness

- Rapid onset disease is possible

Clinical signs of illness

- Due to haemolyticanaemia (destruction of the red blood cells). Pale mucus membranes, jaundice, weakness, fast breathing, red urine, collapse, death

Treatment

- May not be curative

Ehrlichiosis:

Cause of Ehrlichiosis

- A rickettsial parasite in the white blood cells

Vector

- Tick

Where is this Tick found?

- France, Corsica, Spain, Italy and Portugal, and further north to Germany, Belgium and Holland

Feeding activity

- As for Babesiosis

Prevention

- As for Babesiosis

Speed of onset of illness

- Rapid onset disease, sub-clinical infection (i.e. the parasite is in the body but does not cause signs of illness) or chronic infection (i.e. causing a slower, long term illness) are all possible

Clinical signs

- Fever, anorexia and enlarged lymph nodes

Treatment

- Vets most commonly prescribe the antibiotic doxycycline to treat ehrlichiosis in dogs. It is typically given once a day for three to four weeks. Other medications can also be used when the situation warrants.

If a dog receives treatment in a timely manner, his condition will usually begin to improve rapidly, often within just a day or two, and the prognosis for complete recovery is good. In more severe cases, additional treatments (e.g., intravenous fluids, blood transfusions, immunosuppressive medications, and/or pain relievers) may also be necessary.

Heartworm (Dirofilariasis):

Cause of Heartworm

- Nematode worm found in pulmonary arteries (those in the lungs) and heart

Vector

- Mosquitoes

Where do the Mosquitoes live?

- From northern France south to the Mediterranean. Much of the USA and Canada

- Hyper-endemic in the Po Valley in Italy

Feeding activity of Mosquitoes

- Mainly at night but some species feed during the day

- Especially from May to September

Prevention of Mosquito bites

- Small mesh nets or window covers

- Environmental insect repellents – coils and plug-ins

- Scalibor repellent collar for dogs and Advantix

Prevention of disease

- Drug prophylaxis (preventative treatment) using Milbemax tablets – start a month before exposure, then give monthly until one month after return to the UK. Where dogs may have been previously exposed, testing is required prior to treatment. Testing comprises blood tests and chest X-rays (radiographs)

Clinical signs

- Associated with respiratory disease and heart failure

Treatment

- Dogs with heartworm disease will initially receive treatment needed to stabilise their condition. They will then be given medication to kill circulating microfilariae, and most will undergo a series of three injections over a month’s time to kill adult worms in the heart and lungs. Hospitalisation when these injections are given, and possibly at other times, is necessary so that your vet can watch closely for side effects. Prednisolone and doxycycline are also typically prescribed to reduce the chances that the dog will react badly to the death of the worms. Other treatments may be needed based on an individual dog’s condition.

If a dog has caval syndrome, a surgical procedure will be necessary to remove adult worms from the right heart and pulmonary artery by way of the jugular vein. Most dogs with caval syndrome die regardless of treatment.

Summary General Recommendations:

Ticks

Prevent tick attachment

- Scalibor collars (dogs)

- Advantix spot-on (dogs)

Kill Ticks

- Frontline (cats)

- Advantix spot-on (dogs)

Daily check for ticks and remove any found using a Tick Hook

Sandflies and Mosquitoes:

- Keep your pet inside at times of peak activity

- Use meshes/netting over windows

- Use environmental repellents

- Scalibor collar (dogs) or Advantix (dogs)

Heartworm prevention:

- Monthly Milbemax tablets or fortnightly Advocate

- Start one month before exposure and continue until one month after return

Please note:

It is important to take great care when removing ticks to ensure that the mouth parts are fully removed. Failure to do so may cause an abscess or granuloma (inflamed lump) to develop. To ensure safe removal we recommend using a specially designed Tick Hook. These come with instructions for safe tick removal.

All of the above products can be supplied by our clinic. Please note that for licensed veterinary products to be dispensed, your pet needs to be under our care which may require a clinical examination if we have not seen your pet for some time.

FELINE HYPERTENSION

by admin on May 1st, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

To encourage awareness of Feline Hypertension this month we are offering the owners of all cats over 8 years of age with no previous history of hypertension a FREE Screening test with one of our nurses.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, usually occurs in cats secondary to other diseases. The most common diseases to cause high blood pressure in cats are chronic renal failure (kidney disease), hyperthyroidism and anemia. Cushing’s disease and certain forms of cancer can also cause high blood pressure.

Hypertension is a serious problem in the cat, as it can cause blindness and strokes, just as in people. The first symptom seen is usually sudden blindness from retinal detachment – the high blood pressure literally blows out the back of the eye. If retinal detachment is caught early, with prompt and aggressive drug treatment the retina will sometimes reattach itself at least partially, and some vision will be restored. Many cats, however, will be permanently blind as a result. Owners will sometimes notice the cat’s pupils are fixed and fully dilated, or only respond very slowly and sluggishly to light. This is an emergency situation which should be treated as soon as possible.

The other common symptom of untreated high blood pressure is bleeding into the brain. Cats may suddenly show signs of disorientation, circling around and around in one spot, or otherwise acting strange. Some cats will wander the house crying as if distressed.

Ideally, high blood pressure should be diagnosed and treated before the cat becomes blind or suffers brain damage. If your cat has been diagnosed with chronic renal failure, hyperthyroidism or anemia, a blood pressure check will probably be recommended as well.

Some cats with high blood pressure will have heart murmurs or abnormal heart rhythms. If your veterinarian picks up a heart murmur or arrhythmia in a cat, especially an older cat prone to kidney or thyroid disease, a blood pressure check will be recommended. We may also pick up on high blood pressure when we draw a blood sample – if the blood gushes into the syringe without our having to pull back on the

plunger, the cat’s blood pressure is probably very high.

About 65% of cats with chronic renal failure have some degree of hypertension. This is a serious problem because hypertension in turn worsens the kidney disease. It becomes a vicious cycle in which the high blood pressure worsens the kidney disease, which increases the blood pressure even more, which then worsens the kidney disease, etc. Any cat diagnosed with chronic renal disease should have a blood pressure check on a regular basis.

In cats with hyperthyroidism the hypertension is usually temporary. Once the thyroid disease is controlled with medication or radiation treatment, the blood pressure goes back down. Treatment for high blood pressure in this disease is usually only needed for a few weeks to months. Treatment is still important, however, to prevent blindness and brain damage.

Although blood pressure measuring is important to monitor, it can also be difficult to do accurately in cats. Most cats are stressed and nervous at the veterinary clinic, and some are hostile. Blood pressure readings will probably be higher than they would be if measured when the cat was at home in its own environment. If a cat is aggressive or terrified, readings may not be possible at all. We will advise you as to whether an accurate blood pressure reading is possible in your cat.

We try to make the experience as stress free as possible, in a quiet room. The measurement itself is painless, just as it is in humans, but the cat may be frightened by the procedure. The cat needs to be held still, and a Doppler monitor is used to get the measurement. The monitor makes a noise which may frighten to some cats. The feeling of the cuff on the leg also makes some cats nervous, as does being held.

The goal of treatment is to decrease the blood pressure gradually to avoid a sudden decrease in blood flow to the kidneys, which will make kidney disease worse. In cats with chronic renal failure and high blood pressure, the pressure should be rechecked every 3-7 days, depending on how good the first reading was. Once two good readings on two successive visits are obtained, the cat is considered stable on the medication. The blood pressure is then rechecked along with kidney blood testing about every three months. Drug treatment will be necessary for the rest of the cat’s life.

There are two medications commonly used to treat hypertension. Amlodipine is usually tried first. If the response is not adequate, we may switch to benazapril. Occasionally, a cat will need both amlodipine and benazapril to control the high blood pressure.

For cats with chronic renal failure but a normal first blood pressure check, rechecks are recommended every 6-12 months. Hypertension may show up later in the course of the disease, as kidney function gradually worsens with time. In cats recently diagnosed with hyperthyroidism, the blood pressure may be high. If affirmative we will prescribe a two to three week course of blood pressure medication for the cat while the thyroid level is coming down in response to treatment. Once the thyroid level is back in the normal range, the medication can usually be stopped.

Cats that have already suffered blindness or visual impairment from hypertension usually get around well in their own home with some modifications to the environment. Your cat may not be able to find its way to the basement litter tray any more but blind cats rarely stop using the tray as long as it is accessible to them. Be sure the food and water bowls are also accessible without climbing or jumping. Dabbing some perfume or cologne on table legs and doorways once a week at first with help your pet to smell where it’s going and makes navigation easier.

Be sure to call us if you have trouble administering your cat’s medication or you notice any change. We are always glad to help!

See website: http://www.amodeus.vet for further information

HOME MONITORING OF HEART FAILURE

by admin on April 3rd, 2018

Category: News, Tags:

This article provides key aspects of monitoring your pet with heart failure at home and explains the parameters to record. These need to be monitored frequently (daily) in the few weeks after initial diagnosis and commencement of medications, or at any time when things are unstable, such as a relapse or progression in symptoms. The frequency of recording can be less (weekly) when everything is stable and your pet is happy. You can record all of these using a diary or computer database. Remember to always bring your record back with you to every visit.

Sleeping Respiratory Rate (SRR)

This should be recorded when your pet has had a period of rest and is asleep. This might be by your feet or in bed. It is best to record this when your pet falls asleep when you are in the room, as opposed to going into the room where your pet is already asleep – as they usually wake up when you enter.

Breathing is often best seen when your pet is lying on the side and the chest and flank can be seen to rise and fall. A breath in and then out is recorded as one breath. The rate is given as the number of breaths in 1 minute.

Heart rate (HR) at rest:

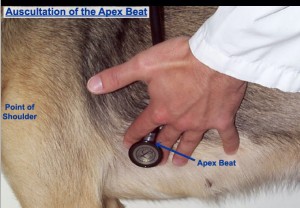

This is more difficult to record, but it is possible to do and it provides very useful information. The heart rate when ‘in the vets’ is always somewhat elevated because of excitement or nervousness, so does not represent the real heart rate at home.

The heartbeat can be felt by placing your hand on the chest over the heart, just inside the ‘armpits’ on the left side, but can be either side of the chest. You could purchase a cheap stethoscope and learn to listen to the heart rate. Feeling the pulse in the leg does not always represent the heart rate, as some abnormal or weak heartbeats might not produce a palpable pulse, so we prefer that you do not use this method.

You could purchase a heart rate monitor, and whilst these are a little more expensive, over the course of your pet’s life, often represent good value for money. The rate is given as the number of heartbeats in 1 minute.

Weight

One of the effects of heart failure is the accumulation of excess fluid in the lungs (oedema), chest cavity (pleural fluid) or abdomen (ascites). One litre of fluid is equivalent to 1 kg in weight. Thus monitoring your pet’s body weight is a useful means to track the loss or gain in fluid accumulation.

We recommend weighing your pet weekly. It is often best to use the scales at your own vets for consistency and accuracy.

Appetite

Your pet’s appetite may reflect his/her well-being. It is a simple scoring system, comparing appetite to when your pet was well prior to this illness and is as follows:

Appetite Scores:

1 Ate hardly anything

2 Ate much less than normal

3 Ate a little less than normal

4 Normal

5 Ate very well

Exercise

Once any congestion has resolved with treatment, a return to some exercise is good for the well-being of your pet and for the circulation. The ability to exercise also reflects the ability of the heart to function and circulate blood, so it can be a useful indication of how well your pet is doing. Again this is a simple scoring system, comparing the ability to exercise to when your pet was well prior to this illness and is as follows:

Exercise Scores:

1 Can hardly exercise at all

2 Is exercising much less than normal

3 Is exercising a little less than normal

4 Normal

5 Exercises very well

Cough

Coughing is a common symptom in dogs (it is rare in cats). This can occur for a few reasons. One is that an enlarged heart presses on the windpipe, compressing it and this triggers a cough; it probably feels like something is stuck in the throat. Another is the accumulation of fluid in the lungs (oedema), this needs to be moderately severe to trig, of course,h. Then of course a dog (or cat) can be coughing secondary to various lung conditions such as bronchitis (or asthma in cats). Monitoring the frequency and severity of a cough can therefore be useful.

Cough Scores:

1 Very often, daily

2 Often, daily

3 Often, weekly

4 Occasionally, weekly

5 None

The Happiness Factor

This is a surprisingly useful overall score of how well your pet is. It is a simple scoring system, comparing how happy your pet is compared to when your pet was well, prior to this illness and is as follows:

Happiness Scores:

1 Very unhappy

2 Much less happy than normal

3 A little less happy than normal

4 Happy, back to normal

5 Really happy