News

Archive for the ‘News’ Category

Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS)

by admin on May 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

‘BAOS: Too much soft tissue and not enough space’

Brachycephalic breeds are those with squashed up faces! We love them and they are great characters but selective breeding over many generations has encouraged the skull to be progressively shorter over time. However, the amount of soft tissue in the nose and throat has remained the same. These soft tissues include the soft palate, turbinates (cartilage inside the nose) and tongue. These are all crammed into a smaller space. In addition, a lack of underlying nasal bones also causes the nostrils to become very narrow appearing like small slits instead of open holes.

Breathing problems

The crowding of this tissue inside the nose and the back of the throat obstructs airflow through the upper airways. This is why many of these dogs are forced to breathe through their mouth and pant. In an attempt to draw air in through this cramped space many affected dogs will put much more effort into their breathing. This is why if you watch these patients closely you will see them using their abdominal muscles as bellows during breathing. A good analogy for this is comparing how difficult it would be to suck through a very narrow straw compared to a normal one.

The ‘knock-on’ effects of laboured breathing

Unfortunately, the increased effort creates a suction effect in the back of the throat at the opening into the trachea (windpipe). This opening into the windpipe is called the larynx (or voice box in people). It has a tough cartilage frame which keeps it open wide. However, constant suction in this region over a period of months can cause it to fold inwards further narrowing the airway and causing serious breathing difficulty. This secondary problem is called laryngeal collapse.

What about the nose?

The nose is an important part of the anatomy and it functions to warm and humidify the air before it is inhaled into the lungs. It is a crucial part of how dogs maintain a normal body temperature. If affected dogs can’t breathe through their nose then this significantly affects their ability to thermoregulate and explains why they have poor heat tolerance. Of course, it is no surprise that many patients present with breathing problems in the summer months.

What are the clinical signs of Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS)?

The main clinical signs in approximately increasing the order of concern include:

- Loud snoring during sleep

- Noisy breathing (especially during excitement or exercise)

- Panting

- Poor ability to exercise

- Heat intolerance

- Choking on food

- Regurgitating

- Laboured breathing

- Development of blue gums or tongue

- Fainting

Aren’t some of these signs just ‘Normal’ for the breeds?

Yes and no. The problem is that a large number of brachycephalic dogs show the signs at the milder end of the above spectrum and our tolerance of what is normal for these breeds has become skewed. We frequently see patients coming into our clinic for unrelated problems with marked breathing difficulty. When questioned their owners often state that they consider these signs as normal for the breed. They often add that most other dogs of the same breed that they come across on walks sound and react the same which reinforces this notion! Therefore it is important that we get the message across that these signs are abnormal and if your dog is displaying some of them then a veterinary opinion should be sought.

Be proactive!

A proactive approach is beneficial as there are many surgical treatments which can be carried out that will help these patients breathe. Although these treatments will not produce a ‘normal’ airway it will invariably improve airflow, thus improving their quality of life and ability to exercise. The latter is particularly important as obesity makes this problem significantly worse. Intervention early in life can reduce the amount of suction at the back of the throat and therefore reduce or delay the development of secondary laryngeal collapse for which there are limited options available.

See the excellent new film on BAOS by the Kennel Club on Youtube entitled ‘Dog Health: What Is Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome?’

Epilepsy in Dogs

by admin on April 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Epilepsy means repeated or recurrent seizures or “fits” due to abnormal activity in the brain. Electrical activity is happening in the brain all the time however in some patients an additional and abnormal burst of electrical activity can occur which causes a fit. Some dogs will just have one fit but in others it becomes a regular event – this is Epilepsy. It is important to realise that Epilepsy is not a disease in itself but the sign of an abnormal brain function. The most commonly diagnosed form of epilepsy is referred to as Primary Epilepsy and is more common in certain breeds. Epilepsy does occur in cats but is much less common.

Are all fits the same?

No and as It is very likely your vet won’t see the fit taking a short video can be extremely helpful to them in deciding on the best course of action. Many types of seizure have been described in dogs and cats. The most common type is the grand mal which is the dramatic, typical fit where the patient lies on the floor and the whole body twitches and convulses rhythmically. Partial epileptic seizures that affect only one part of the body can also occur. These are less common and can be difficult to differentiate from other unusual non-epileptic movement disorders.

The seizure frequency is extremely variable between dogs (from many seizures a day to a seizure every few months). Despite being born with this functional brain disorder, dogs with primary epilepsy usually do not start seizuring before the age range of 6 months to 6 years. In the absence of disease affecting the brain, animals are typically normal in between the epileptic seizures.

What causes epilepsy?

The exact mechanism is unknown but in many cases the tendency to develop epilepsy is thought to be passed on genetically. In Primary epilepsy there is no obviously abnormal brain tissue and it is due to a chemical imbalance or to some ‘faulty wiring’ in the brain.

What is Secondary Epilepsy?

Secondary epilepsy is when the fits are being caused by another brain disorder such a brain tumour, an inflammation or infection of the brain (encephalitis), a brain malformation, a recent or previous stroke or head trauma. In other words there is an identifiable cause for the regular fits and there is some structurally abnormal brain tissue.

How is Epilepsy diagnosed?

The diagnosis of primary epilepsy is unfortunately a diagnosis of exclusion after elimination of other causes. There is no definitive diagnostic test for this condition and all investigations such as blood tests, brain scans and laboratory analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which surrounds the brain and spinal cord, will all come back as completely normal!

Can you cure epilepsy?

Primary Epilepsy is unfortunately a condition that the animal is born with and as such it cannot be cured. Using anti-epileptic medication such as phenobarbitone will prevent some patients having any more fits. Although complete control is the goal of treatment, in most circumstances ‘successful treatment’ is a balancing act of reducing the frequency and severity of the seizures to a low level whilst avoiding unacceptable side effects of the drugs. So a patient may still have some fits despite being on treatment.

When should medication be started?

This isn’t a black and white issue. A substantial number of dogs will only have one fit in their entire lifetime and so if every dog was started on treatment after its first fit then all these dogs would be receiving medication unnecessarily. However, there is some evidence to suggest that early treatment offers better long-term control of the seizures as compared to animals that are allowed to have numerous seizures prior to the onset of treatment. We also have to take into account that anti-epileptic medications can have side effects and getting things under control will often place significant demands on you as the pet owner and carer.

Elbow Dysplasia in Dogs

by admin on March 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Osteochondrosis or osteochondritis dissecans(OC or OCD)

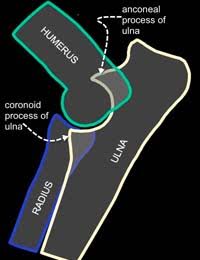

Osteochondrosis or osteochondritis dissecans(OC or OCD)- Fragmented coronoid process (FCP)

- Ununited anconeal process (UAP)

These conditions may be related to a poor fit between the three bones that make up the elbow joint. This poor fit or ‘incongruity’ can be seen on X-rays or by CT or MRI examination. In some patients, it may be difficult to identify because it is only present when the dog does certain activities, and sometimes this poor fit may have been present briefly during the dog’s development and is no longer present when investigations are performed.

These primary problems tend to develop when the puppy is only a few months of age and will commonly affect both elbow joints. Once a primary problem has started, secondary change soon follows. Secondary change takes the form of abnormal joint wear and arthritis. These secondary changes may have consequences for the rest of the dog’s life.

Are certain breeds prone to getting Elbow Dysplasia?

Elbow Dysplasia is a significant problem in many breeds worldwide. It is recognised in numerous breeds although large breeds seem to be most affected – particularly Labrador Retrievers, Newfoundlands, Golden Retrievers, Boxers, Rottweilers and German Shepherd Dogs. As investigation methods have improved we are increasingly recognising it in smaller breeds too.

Why do dogs get Elbow Dysplasia?

Elbow Dysplasia is a multifactorial disease which means that a number of factors influence its occurrence. Genetics plays an important role although the precise genetic basis of Elbow Dysplasia remains undetermined. Other factors that are thought to influence the disease include growth rate, diet, and level of activity.

How do I know if my pet has Elbow Dysplasia?

Not all dogs with Elbow Dysplasia will show obvious clinical signs of lameness. This may be because the condition is mild or because similar changes exist in both elbows which may mask the lameness. Clinically affected dogs with Elbow Dysplasia commonly show stiffness or lameness between 5 and 12 months of age. Typically owners describe that their dog is stiff after rest and after exercise but improves with light activity. Others will observe that their dog’s front feet begin to turn out. It is thought that this is an adaptation to elbow pain and is the dog’s way of relieving it.

What tests may be required?

Clinical examination may determine that the elbow joint is painful or swollen, although initially, the lameness may be difficult to localise to a particular joint. Confirmation of the diagnosis of Elbow Dysplasia is made by performing further investigations which would typically be X-rays or CT examination. X rays will often be able to determine whether your dog has elbow dysplasia either by identifying the primary problem or the osteoarthritis that occurs as a result. Three bones (humerus, radius, and ulna) combine to form the elbow joint and these overlap on radiographs. This makes identification of the primary lesion problematic in some cases.

Elbow radiographs and CT/MRI scans are important tests for detecting elbow dysplasia in dogs. CT/MRI examination is an excellent method of looking at the detailed structure of the joint and determining the precise nature of Elbow Dysplasia. It provides additional information to radiography and this can be useful when planning surgical treatments, especially in more complex cases.

Head Tilt In Dogs

by admin on February 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What does it mean if my dog has a Head Tilt?

A persistent head tilt is a sign of a balance (vestibular) centre problem in dogs. It is very similar to ‘vertigo’ in people and is often accompanied by a ‘drunken’ walk and involuntary eye movements, either side to side or up and down.

The feeling that the room is spinning due to the eye movements is what causes a feeling of nausea in both people and dogs. The signs may not be as severe as mentioned here and can just consist of a mild head tilt. Signs often seen associated with a head tilt but unassociated with balance abnormalities include a facial ‘droop’ and deafness.

Causes of a head tilt

A head tilt represents a disorder of the balance centre. However, the balance centre resides in the inner bony portion of the ear as well as the brain. So a head tilt could represent a simple ear problem or a very serious brain disease.

Ear problems which are responsible for head tilts include:

- Infections

- Polyps

- Reactions to topical drops or solutions if the ear drum is damaged

- Hits to the head

- (Occasionally) ear tumours

- (Rarely) a genetic abnormality affecting puppies, especially those of the Doberman breed

- Idiopathic vestibular disease

The most common cause is what is called idiopathic vestibular disease. There is no known cause of this disease, a variant of which is also seen in people. The signs can start very suddenly and be accompanied by vomiting in severe cases. This condition, however, will resolve given time without any specific treatment.

Brain diseases responsible for balance centre dysfunction can include:

- Tumours

- Trauma

- Inflammation

- Stroke

- Rarely, similar signs can be seen in dogs that are receiving a specific antibiotic called metronidazole. Recovery will often take place within days of stopping this medication

Clinical signs of vestibular disease – is it the ear or is it the brain?

In addition to a head tilt, signs of vestibular disease (balance centre dysfunction) include ataxia (a drunken, falling gait) and nystagmus (involuntary eye movements). There are several signs to look for which help separate out whether the origin of the disease is inner ear or brainstem (Central Nervous system – CNS).

Central nervous system localisation will often be associated with weakness on one side of the body that can manifest as ‘scuffing’ or even dragging of the legs, in addition to lethargy, and sometimes problems eating and swallowing, or loss of muscle over the head.

A balance problem associated with an inner ear disease is not likely to be associated with any of these signs. However, some dogs will exhibit a droopy face and a small pupil on the same side as the head tilt.

Tests recommended for a dog with a head tilt

Evaluation of an animal with a head tilt includes physical and neurologic examinations, routine laboratory tests, and sometimes x-rays. Your veterinary surgeon may carry out a thorough inspection of the ear canal, which may require sedation of your dog – this can be useful to rule out obvious growths or infections. Additional tests may be recommended based on the results of these tests or if a metabolic or toxic cause is suspected. Identification of specific brain disorders requires imaging of the brain, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Collection and examination of cerebrospinal fluid, which surrounds the brain, is often helpful in the diagnosis of certain inflammations or infections of the brain.

How do we treat head tilt in dogs

Treatment for vestibular dysfunction will focus on the underlying cause once a specific diagnosis has been made. Supportive care consists of administering drugs to reduce associated nausea and/or vomiting. Travel sickness drugs can be very effective. These must only be given following advice from your veterinary surgeon. Protected activity rather than restricted activity should be encouraged as this will potentially speed the improvement of the balance issues.

Outlook (prognosis) for head tilt in dogs

The prognosis depends on the underlying cause. The prognosis is good if the underlying disease can be resolved and guarded if it cannot be treated. The prognosis for animals with an idiopathic vestibular disease is usually good because the clinical signs can improve within a couple of months.

Myaesthenia Gravis in dogs

by admin on January 3rd, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

In this article, we will look at an important but quite rare cause of muscular weakness and collapse in dogs…Myasthenia Gravis.

What is myasthenia gravis?

Myasthenia Gravis (pronounced my-as-theen-ia grar-viss) is a possible cause of generalised weakness in dogs and occasionally cats. It also occurs in humans.

What happens in myasthenia gravis?

Nerves work like small electrical cables. They pass an electrical current into the muscles to make them contract or shorten. The nerve doesn’t directly stimulate the muscles to contract; instead, it releases a chemical into a small gap that exists between the end of the nerve and the outer lining of the muscle. This gap is called the neuromuscular junction. The chemical that is released is called a neurotransmitter and in most of our muscles this neurotransmitter is a chemical called acetylcholine. It is packaged into tiny pockets at the end of the nerve and it is released when a nerve impulse comes along.

In a fraction of a second the acetylcholine spurts out from the end of the nerve and sticks to the outer membrane of the muscle. This allows a small electrical current to flow into the muscle and the muscle contracts. To create this effect the acetylcholine must attach to a specific receptor on the muscle surface. This can be likened to a lock and a key opening a door. The lock is the receptor and the key is the acetylcholine. The two fit together perfectly and a microscopic door in the muscle wall then opens to allow the electrical current into the muscle cell. It has to be an exact fit so that the muscle only contracts when the nerve ‘tells’ it to.

In myasthenia gravis this chemical transmission across the neuromuscular junction becomes faulty and if the muscles are unable to contract properly they then become weak. Muscle weakness can affect the limbs so that animals are unable to stand or exercise normally but can also affect other muscles in the body. The muscles of the oesophagus (the pipe carrying food from the mouth to the stomach) are often weak in dogs with myasthenia gravis and this means that affected animals may have problems swallowing and often bring back food after eating.

What causes myasthenia gravis in dogs?

Some animals are born with too few acetylcholine receptors on the surface of their muscles i.e. it is a congenital disease. More commonly however, myasthenia gravis is an acquired condition that comes on later in life and here it is caused by a fault in the animal’s immune system.

Antibodies usually attack foreign material such as bacteria and viruses. In acquired myasthenia gravis, the immune system produces antibodies which attack and destroy the animal’s own acetylcholine receptors. No-one really knows why the immune system should suddenly decide to attack these receptors in some dogs. In rare cases, it can be triggered by cancer.

Whatever the reason, when the number of receptors is reduced, acetylcholine cannot fix itself to the muscle to produce normal muscle contractions and muscle weakness results.

How do I know if my pet has myasthenia gravis?

The typical picture is a severe weakness after only a few minutes of exercise. This weakness might affect all four legs or only affect the back legs. It is frequently preceded by a short stride, stiff gait with muscle tremors. The patient eventually has to lie down. After a short rest they regain their strength and can be active again for a brief period before the exercise-induced weakness returns. Other signs of myasthenia are related to effects on the muscles in the throat and include regurgitation of food and water, excessive drooling, difficulty swallowing, laboured breathing and voice change. In the most severe form, the animal can be totally floppy and unable to support its weight or hold its head up.

Which dog and cat breeds are most commonly affected?

The acquired form is seen most commonly in Akitas, terrier breeds, German Shorthaired Pointers, German Shepherd Dogs and Golden Retrievers. In cats it is Abyssinians and a close relative, Somalis. The rare congenital form has been described in Jack Russell Terriers, Springer Spaniels and Smooth-haired Fox Terriers.

What conditions can it be confused with?

Diseases of the muscles (a myopathy) or nerve disease (a neuropathy) can mimic signs of myasthenia gravis and should be considered in the diagnosis.

How is myasthenia gravis diagnosed?

Your vet will often be very suspicious based on the clinical signs and medical history alone. A blood test can be performed to detect antibodies directed toward the acetylcholine receptor. Another test that is sometimes performed is known as the ‘Tensilon test’. Here the patient is given a short-acting antidote that boosts the effects of acetylcholine on the muscle. It is injected into a vein and in patients that have myasthenia gravis there will be a dramatic increase in muscle strength immediately after injection and collapsed animals may get up and run about. However, the effects wear off after a few minutes.

In specialist centres an electromyogram (EMG) may be performed. An EMG machine can be used to deliver a small electrical stimulation to an individual nerve or muscle in an anaesthetised animal. Using an EMG machine we can measure how well the muscles respond to stimulation.

The rare congenital form of myasthenia is usually diagnosed by special analysis of a muscle biopsy.

Chest X-Rays will also be performed to look for cancer in the chest cavity which can trigger myasthenia gravis. The chest x rays will also help to evaluate possible involvement of the oesophagus and to detect pneumonia secondary to inhalation of food.

Can myasthenia gravis be treated?

Specific treatment of myasthenia gravis is based on giving a long-acting form of a drug that works like the Tensilon in the test described above. These chemicals boost the effects of acetylcholine on the muscle cells and improve the transfer of the electrical signal from the nerves to the muscles. It may also be necessary to give drugs that will suppress the immune system to stop it attacking the acetylcholine receptors. This will make the patient more susceptible to infections and so they would require careful monitoring whilst on immunosuppressive drugs, particularly with the increased risks of pneumonia is myasthenia patients.

What is the outlook for dogs and cats with myasthenia gravis?

The outlook is generally good unless the patient develops a secondary severe pneumonia due to the inhalation of food material. Treatment usually lasts many months and your vet will need to re-examine your pet on a regular basis to check that they are improving. Repeated blood tests to measure the levels of the antibodies against the acetylcholine receptors will also be required.

Myasthenia gravis is a serious and very debilitating disease. However, with an early diagnosis and a high level of care the symptoms may be controlled so that your pet has an active life. Some patients may make a full recovery.

POISONS PUT LITTLEHAMPTON PETS IN PERIL

by admin on December 1st, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

Poisons put Littlehampton pets in peril, as 95% of vets report cases.

Fitzalan House Vets warn local pet owners to guard against poisonous perils after the British Veterinary Association’s (BVA) Voice of the Veterinary Profession survey showed 95%of South-East region companion animal vets had seen cases of toxic ingestion or other toxic incidents over the last year.

Across the UK, vets saw on average one cases of poisoning every month, with chocolate (89%), rat poison (78%) and grapes (60%) the most common poisons that vets had treated. Other poisons involved in the cases vets had seen included:

Other less common cases involved xylitol poisoning from chewing gum, poisoning from wild mushrooms and fungi, as well as horse worming products ingested by dogs.

Vets know that sometimes owners can take every precaution and accidents still happen. If an owner suspects their pet may have ingested or come into contact with any harmful substance they should contact us immediately on 01903-713806 for advice.

BVA President Gudrun Ravetz said:

“These findings from BVA’s Voice of the Veterinary Profession survey show how common incidents of pet poisoning are and underline that owners must be vigilant especially with prying pets. The top five poisoning cases seen by vets include foods that are not toxic to humans but which pose a significant risk to pets such as dogs, like chocolate and grapes, alongside other toxic substances such as rat poison and antifreeze. Owners can take steps to avoid both perils – keep human food away from and out of reach of pets and make sure other toxic substances and medicines are kept securely locked away in pet-proof containers and cupboards.”

Corneal Ulcers in Dogs and Cats

by admin on November 3rd, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

Corneal ulcers are defects of the ‘cornea’, the clear ‘window’ of the eye.

What is the cornea?

The cornea is a very special tissue that is completely transparent. In contrast to the skin, it lacks pigment and even blood vessels to maintain its transparency. The cornea is very rich with nerves, making it a very sensitive tissue. This is the reason why even small particles such as dust on the surface of the eye can be so uncomfortable.

The cornea is made of three layers:

- a very thin outer layer (epithelium)

- the thick middle layer (stroma)

- a very thin inner layer (endothelium)

All three layers are important for the cornea to work. The outer layer or ‘epithelium’ can be thought of as a layer of cling film that forms the surface of the cornea and protects it from infections. It works as a shield to the eye. The thick middle layer or ‘stroma’ is what gives the cornea its strength and stability.

What are corneal ulcers?

Corneal ulcers are classified by the depth, depending on the layers they affect.

If only the epithelium is missing this is classified as a ‘superficial ulcer’ or surface defect only. If the ulcer reaches into the stroma it is classified as a ‘deep ulcer’.

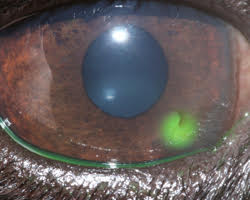

corneal ulcer

While superficial or surface ulcers are uncomfortable and present a risk of infection to the eye; the eye is not at risk of bursting unless additional problems occur. However when the ulcer gets deep the eye becomes weak and can even perforate. Deep ulcers lead to visible indentations on the surface of the eye and can be accompanied by inflammation inside the eye.

Signs of corneal ulcers usually include eye pain (squinting, tearing, depressed behaviour) and ocular discharge, which can be watery or purulent. Sometimes a lesion may already be visible on the surface of the eye. In this case it is particularly important to seek help from your veterinary surgeon as soon as possible.

How is a corneal ulcer diagnosed?

To diagnose a corneal ulcer your vet may use a special dye that highlights any defects of the surface layer by staining the underlying tissue green (see the image at the start of this article). This test is called the fluorescein test.

Why do corneal ulcers occur?

When the presence of an ulcer has been confirmed, it is important to try and find a reason for it. Most ulcers occur due to an initial trauma. This is more likely to happen in dogs and cats with very prominent eyes (also called ‘brachycephalic’ animals), for example in Pugs and Pekingese dogs or Persian cats. In cats the flare up of a Feline Herpes Virus infection is also a common cause for the development of a corneal ulcer. Many conditions can increase the risk of corneal ulcers. Reduced tear production is a common contributing factor, but other conditions such as an incomplete blink, in-rolling of the eyelid (also called ‘entropion’) or eye lid tumours may contribute to the occurrence, but even more so may interfere with the healing process.

How are corneal ulcers treated?

To treat an ulcer it is essential that the underlying cause is identified and if possible corrected. This will stop the ulcer from getting worse and allow the eye to heal as quickly as possible. The treatment plan will usually include eye drops to treat or prevent infection but may include other medication depending on the cause and severity of the ulcer. Painkillers and/or antibiotics by mouth may also be necessary.

Do any corneal ulcers require an operation?

If an ulcer is deep or the cornea is even ruptured, surgery is required to save the eye. Different techniques are available, but all of them place healthy tissue into the defect to stabilise the cornea. Very small suture material, as thin as a human hair, is used to repair the cornea and an operating microscope should be used to handle the small and very fine structures of the eye.

In most patients the healthy tissue is taken from the same eye from an area adjacent to the corneal ulcer.

The pink tissue next to the cornea (the conjunctiva) can be used for that to place a ‘conjunctival pedicle graft’ into the defect. More commonly, healthy corneal tissue attached to conjunctiva is used as it provides more strength to the wall of the eye. This is called a ‘corneoconjunctival transposition’ (Figure 5).

Corneal grafts are also possible but rely on the often limited availability of donor corneal tissue. Grafting surgeries are very successful in saving eyes, but can lead to scaring of the cornea leaving it less transparent in areas.

How can corneal ulcers be prevented?

Particularly in patients with prominent eyes, regular eye examinations should be performed to detect weaknesses in the corneal health. Indications of that may include white or brown marks on the surface of an otherwise comfortable eye or sticky discharge that continues to recur. Any painful eye should be presented to a veterinary surgeon as soon as possible.

Eyes may be cleaned with tap water that ideally should be boiled and cooled down again, using a lint-free towel. This should however not replace or delay the visit to a veterinary surgeon, as many ulcers require medication to achieve fast healing and prevent ill effects to the transparency of the cornea and therefore the sight of the dog or cat. Particularly; if a deep indentation or bulging tissue is noted on the surface, the eye should not be manipulated to prevent any additional damage.

Corneal ulcers are best prevented but if they are present they should be treated as soon as possible to stop them from getting bigger and deeper.

Addisons Disease

by admin on October 7th, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

What is Addison’s disease?

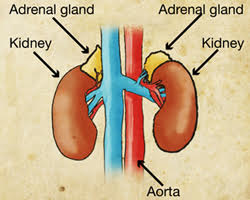

Hypoadrenocorticism (or Addison’s disease as it is more commonly known) is a disease where the body does not produce enough steroid hormone. Steroids in the body are primarily produced by the two adrenal glands which are found in the abdomen close to the left and right kidneys. The main steroid hormones produced by the body are called aldosterone and glucocorticoid.

Aldosterone is important in the maintenance of normal salt and water balance in the body. Glucocorticoids have widespread effects on the management of proteins and sugars by the body.

Glucocorticoid release from the adrenal glands is under the control of a substance produced in a gland in the brain called the pituitary gland. Aldosterone release is regulated by a hormone system and by blood potassium levels.

What causes Addison’s disease?

Addison’s disease is normally caused by destruction of tissue of the adrenal gland.In the majority of cases the destruction does not have an identifiable underlying cause (this is called ‘idiopathic disease’).In most cases the adrenal glands stop producing both aldosterone and glucocorticoid (known as ‘primary hypoadrenocorticism’). Occasionally, only glucocorticoids are lacking (known as ‘atypical hypoadrenocorticism’).

Sometimes Addison’s disease occurs in combination with diseases of other glands such as hypothyroidism (this is a disease that causes thyroid hormone levels in the blood stream to be low).

Which animals are at greater risk of developing Addison’s disease?

Addison’s disease is a rare disease in the dog; however, it probably occurs more often than is recognised. It is a very rare disease in the cat. Any breed of dog can be affected with Addison’s disease but a predisposition has been shown in Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers, Bearded Collies, Portugese water dogs and Standard Poodles. In addition Great Danes, Rottweilers, West Highland White Terriers and Soft Coated Wheaten Terriers appear to be at greater risk. Addison’s disease appears to be a disease of the young and middle-aged dog. Approximately 70% of dogs with naturally occurring Addison’s disease are female.

What are the signs of Addison’s disease?

Presenting signs in Addison’s disease vary from mild to severe and do not typically focus attention on any one major body system. The presentation of sudden onset Addison’s disease (the so called ‘Addisonian crisis’) is collapse and profound dullness. Some patients have a slow heart rate. Addison’s disease is easily confused with many other diseases. The presenting signs in longer standing disease are vague and may include vomiting, reduced appetite, tiredness, weight loss, diarrhoea, increased thirst and increased urination.

How is Addison’s disease diagnosed?

Blood tests can sometimes reveal characteristic changes in salt levels. Kidney numbers can also be elevated and mild anaemia (low red blood cells) is not uncommon. The salt changes occur as a result of a deficiency of aldosterone and subsequent effects on the way the kidney normally handles these salts. The salt changes, specifically a high blood potassium level, can have serious effects on the heart.

A definite diagnosis of Addison’s disease is made by your veterinary surgeon performing an ACTH stimulation test on your dog’s blood. This is a test where blood is taken, a drug (ACTH) is given to try and stimulate the adrenal gland and then a second blood test is taken one hour later. If the adrenal gland fails to respond to the drug, Addison’s disease is diagnosed.

What is the treatment for Addison’s disease?

The immediate treatment of life-threatening Addison’s disease involves the careful administration of fluids (‘a drip’) into the blood stream. Steroids are replaced by injection into the vein.

Once animals are stable they were traditionally gradually moved onto tablet medication. Most animals with Addison’s disease would have been discharged with prednisolone and fludrocortisone. Long term, the majority of animals were managed with fludrocortisone alone and this drug is given once or twice daily. The fludrocortisone dose often needs to be increased with time. In times of stress or illness (veterinary visits, bonfire night, boarding etc) animals will often need a dose of prednisolone in addition to their fludrocortisone and your veterinary surgeon will advise you on what to do in these situations.

Side effects of fludrocortisone can include increased drinking, increased urination, panting and muscle wastage.

Recently a new injectable medication (desoxycortisone pivalate) has become the first veterinary licensed product available for Addison’s disease and is used in place of fludrocortisone. It is intended for long term administration at intervals and doses dependent upon individual response as evaluated by regular blood tests.

What is the outlook for dogs with Addison’s disease?

Once animals are on appropriate therapy, they will require regular veterinary appointments for re-assessment and monitoring. The outlook for many dogs with Addison’s disease is very good with appropriate monitoring and treatment.

Hyperthyroidism in Cats

by admin on September 1st, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

What is hyperthyroidism?

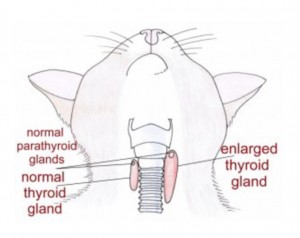

Hyperthyroidism is a relatively common disease of the ageing cat. It is typically the result of a benign (non-cancerous) increase in the number of cells in one or both of the thyroid glands. The thyroid glands are located in the neck although there is occasionally additional tissue within the chest. In the image the red shapes indicate approximately where the thyroid glands are located in a cat. The result of enlargement of the thyroid glands is an increased production of thyroid hormone within the body. Thyroid hormone controls the rate at which cells in the body work; if there is too much hormone, the cells work too fast. Despite many years of research the exact cause of hyperthyroidism remains unknown.

Cats fed almost entirely canned food have been reported to have an increased risk of developing hyperthyroidism but it is likely that there are many causes.

What signs do cats with hyperthyroidism get?

Hyperthyroidism is a disease of middle aged to older cats with an average age of onset of 12-13 years. Increased drinking and increased urination, weight loss, increased activity, vomiting, diarrhoea and increased appetite are often reported. Physical examination often reveals a small lump in the neck which represents an enlarged thyroid gland.

How is hyperthyroidism diagnosed?

A diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is made by the demonstration of increased levels of thyroid hormone in the blood stream. Thyroxine (T4) measurement is the initial diagnostic test of choice.

How is hyperthyroidism in cats managed?

- Medical treatment with either carbimazole or methimazole. These tablet medications are given once or twice daily lifelong. Side effects are uncommon but can occur. They include vomiting and reduced appetite. Very occasionally severe bone marrow or liver problems can be seen.

- Dietary treatment. A specific prescription diet can be fed to hyperthyroid cats to control the disease. The diet is very low in iodine. Iodine is an essential component of thyroid hormone and less dietary iodine means less thyroid hormone is produced. The diet must be fed exclusively (i.e. the cat must eat no other food). Dietary treatment does not lower the thyroid hormone levels as much as the other treatment options

- Surgical treatment. One or preferably both thyroid glands are removed with an operation. A short period of treatment with tablets is recommended prior to surgery. Anaesthesia can be a risk in older cats with hyperthyroidism that possibly have other concurrent diseases. There is a risk of a low blood calcium level after surgery if the parathyroid glands are removed with the thyroid glands. This can be a very serious problem if it is not recognised. Signs of a low blood calcium level can include facial rubbing, fits, tiredness, reduced appetite and wobbliness. Low blood calcium levels are relatively easily managed with oral medication and treatment is rarely necessary lifelong.

- Radioactive iodine treatment. Radioactive iodine is concentrated in the thyroid gland and destroys excessive thyroid tissue. The drug is given by injection under the skin. After the injection, cats need to spend 2-4 weeks in an isolation facility whilst they eliminate the radioactive material. Owners are not able to visit their pets whilst they are in isolation.

- Hyperthyroidism can mask underlying kidney problems and these can become apparent after treatment. Blood tests will be necessary to assess kidney function as well as the thyroxine level during/after treatment.

Can dogs get hyperthyroidism?

Dogs are rarely affected by hyperthyroidism and when it occurs in this species it is normally the result of a diet problem or cancer of the thyroid gland. Treatment for dogs with cancer of the thyroid gland can involve one or a combination of surgery, radioactive iodine, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Unfortunately many dogs have advanced disease by the time the cancer is identified. The majority of dogs with thyroid cancer are not hyperthyroid; they typically retain normal thyroid function or become hypothyroid.

Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) in Dogs

by admin on August 1st, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy (or CIE) is a disease that causes inflammation of the bowel. It has some similarities to a human disease called Crohn’s disease. The inflammation can affect any or all of the stomach, small bowel and large bowel (colon).

What are the signs of chronic inflammatory bowel problems in dogs?

Gastrointestinal (bowel) signs are considered chronic when they have been present for three weeks or more and often clinical signs will come and go. The most common signs associated with gastrointestinal tract disease in dogs include vomiting and diarrhoea. It is important to remember that diarrhoea is a term used to describe altered stool frequency as well as altered stool consistency. Blood and mucus are sometimes seen mixed with the stool. Abdominal pain, ‘squeaky’ guts (this is called ‘borborygmi’) and wind can also be seen. Some cats with chronic inflammatory bowel disease will have no vomiting or diarrhoea and their main sign will be reduced appetite.

What causes chronic inflammatory enteropathy in dogs?

The gastrointestinal signs seen in chronic inflammatory enteropathy arise due to inflammation of the wall of the intestines and/or stomach. The initial cause of the inflammation is often unknown; environmental and genetic factors are thought to play a role along with an abnormal response of the body’s immune system that normally fights infection. Chronic inflammatory enteropathy is generally considered to be an ‘idiopathic’ disease (i.e. a disease with no known underlying cause). The diagnosis is one of exclusion and the diagnosis can only be made if other possible causes of the signs have been excluded.

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy is not a single disease process but it is actually a catch-all term applied to a number of diseases with similar signs. It encompasses food responsive disease (FRD), antibiotic responsive diarrhoea (ARD) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- Food responsive disease is diagnosed when a dog or cat has clinical signs of gastrointestinal tract disease that responds to dietary modification.

- Antibiotic responsive diarrhoea is the term used when gastrointestinal tract signs respond to antibiotic(s) and relapse when antibiotics are stopped. The immune system is thought to have an exaggerated response to ‘normal’ gut bacteria in patients with this disease. It is important to note that antibiotics are not normally indicated in sudden (acute) onset diarrhoea.

- Inflammatory bowel disease has a complex set of underlying causes. It is diagnosed with bowel biopsies that are normally taken with the aid of a camera (endoscope) meaning that surgery is not necessary. It is normally managed with steroid therapy.

Which breeds can be affected by chronic inflammatory enteropathy?

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy can occur in any breed of dog, but certain breeds such as German Shepherds, Soft-coated Wheaten terrier and Irish Setters are known to have an increased risk. It is typically a disease of the middle aged dog but any aged dog can be affected. Cats can also get CIE.

How is chronic inflammatory enteropathy diagnosed?

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy in dogs is normally diagnosed on the basis of history, blood tests, abdominal imaging (typically an ultrasound scan) and sometimes camera evaluation of the upper and/or lower bowel.

How are chronic inflammatory bowel problems in dogs treated?

Dependent upon the severity of the presenting signs, a change in diet may be the first treatment undertaken by your vet. Generally diet trials are performed using a diet that contains a single protein source or one where the proteins are broken down to such a small size (hydrolysed) that they are not recognised as ‘foreign’ by the immune system in the bowel. Some vets prefer to use a single protein source that the patient is unlikely to have been exposed to before (i.e. duck or venison). The diet is normally fed for a minimum of two to four weeks but many dogs respond sooner. If the signs respond to dietary therapy, a diagnosis of food responsive disease is made and dietary therapy is continued long term.

If patients fail to respond to a diet trial or only partially respond, antibiotics may be trialled. If the signs respond, a diagnosis of antibiotic responsive diarrhoea is made.

If the animal’s clinical signs persist despite dietary change or antibiotic therapy, or if the clinical signs are particularly severe, camera examination of the bowel will be performed. This is called endoscopy and the procedure is always done under general anaesthesia in animals. Small biopsies are taken from the bowel during this procedure. Assuming inflammation is identified on the biopsies, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is made. Inflammatory bowel disease is managed with drugs that suppress the immune system’s exuberant response. A steroid called prednisolone is often the first choice medication in both dogs and cats. Additional medications such as ciclosporin and chlormabucil are sometimes used.

What is the outlook for chronic inflammatory bowel disease in dogs?

The outlook for patients with chronic inflammatory enteropathy is dependent upon the severity of the signs and the response to treatment. Many patients will experience intermittent flare ups of their disease long term despite therapy but these are typically milder and shorter in duration once animals are receiving appropriate treatment. Unfortunately a very small proportion of dogs with IBD have disease that is not responsive to drug therapy.